Volume 12, Issue 1 (1-2024)

J. Pediatr. Rev 2024, 12(1): 79-86 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Namdar P, Abdali H, Shiva A, Pourasghar M, Talebi S. Investigating Postpartum Depression in Mothers of Children With Cleft Lip and Palate. J. Pediatr. Rev 2024; 12 (1) :79-86

URL: http://jpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-564-en.html

URL: http://jpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-564-en.html

1- Department of Orthodontic, Dental Research Center, Faculty of Dentistry, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

2- Department of Surgery, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

3- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Faculty of Dentistry, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

4- Department of Psychiatry, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Addiction Institute, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

5- Craniofacial and Cleft Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. ,dds.pnamdar@gmail.com

2- Department of Surgery, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

3- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Faculty of Dentistry, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

4- Department of Psychiatry, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Addiction Institute, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

5- Craniofacial and Cleft Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 398 kb]

(1169 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2513 Views)

Full-Text: (645 Views)

Introduction

Maternal mental health is an important topic with a remarkable impact on children’s health and well-being. Depressed mothers may pay less attention to the health status of their children as a lower rate of referral for age-appropriate care for children and delays in vaccinations have been reported for infants with depressed mothers [1].

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a subtype of major depressive disorder and a serious mental health problem, the onset of which is during the first year after delivery. It commonly occurs within the first 3 months after birth [2]. PPD is experienced by 13% to 19% of childbearing women [3]. The incidence of PPD has been estimated at 11.5% in the United States [4]. Based on a systematic review, the prevalence of PPD is around 25.3% in Iran [5]. Assessment of the related factors to PDD is highly essential since it plays a fundamental role in maternal morbidity and mortality. Evidence confirms the correlation between fetal anomalies and mothers’ PPD scores [6].

Orofacial clefts are among the most common congenital anomalies that appear to affect the incidence of PDD. The mental health of mothers who have given birth to infants with cleft lip and or palate (CL/P) is a vital research topic [7]. One study found that nearly 12% of these mothers exhibited symptoms of depression, as measured by the Edinburgh postpartum depression Scale (EPDS). A significant proportion of these mothers reported self-blame (68.9%), difficulties in coping (59.2%), and feelings of anxiety (57.3%) [8]. Another study conducted in Turkey found that mothers of infants with a cleft experienced increased stress due to various factors, such as postnatal diagnosis, inability to breastfeed, feeding complications, lack of paternal support, perceived challenging infant temperament, feelings of blame and anger, and concerns about the future. These findings underscore the importance of providing comprehensive support and intervention for these mothers [9]. According to a previous study, the risk of depression 2 months after birth was higher among mothers of infants with CL/P, compared with mothers of normal infants [10]. However, limited studies have assessed the incidence of PDD in mothers of infants with CL/P.

Since some critical issues, such as the nutritional status of newborns in the early days after birth, may be affected by maternal mental conditions, assessment of the relationship between PPD and having an infant with CL/P is critical [7]. However, the majority of relevant available studies have focused on the stress level of mothers with CL/P children [11, 12]. Accordingly, this study compares the mothers of infants with CL/P and mothers of normal infants regarding PPD and suicidal thoughts.

Methods

This descriptive-analytical study was conducted on all mothers of children with CL/P, who had recently given birth and presented to the Research Center of Cranial Deformities, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran, from September 2020 to September 2021.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were having a child with CL/P, willingness to participate in the study, and referral at 2-4 weeks after delivery. Mothers taking antidepressants at the time of enrollment, those with a history of untreated prenatal depression, and those who refused to participate in the study were excluded.

Given the study’s objectives, the prevalence of CL/P in Iran (P=0.15) [13], and a confidence interval (CI) of 95%, the sample size was estimated to be approximately 45 cases using the Equation 1. However, to account for potential sample dropouts, the total number of samples was increased to 50. Additionally, 50 mothers with healthy children were included as the control group, resulting in a total of 100 samples examined.

Study design

A questionnaire was completed for each participant covering demographic characteristics, such as age, level of education, occupational status, parity, and history of PPD in previous pregnancy. After completing the questionnaire, the collected information was categorized. EPDS was filled out by a family health associate at a client health center. Each question in this 10-item scale was scored 0 to 3 based on the severity of signs and symptoms. This questionnaire was designed to assess the presence or absence of depression from 6 weeks postpartum afterward. Items 1, 2 and 4 are scored 0 to 3 and items 3 and 5-10, are scored 3 to 0. The items were rated using a 4-point Likert scale. The sum of all item scores was calculated and reported as the PPD score. The EPDS total score can range from 0 to 30, and a score above 12 indicates the presence of PPD. Higher scores indicate higher severity of PPD [14]. The validity and reliability of EPSD have been previously confirmed in Iran by Montazeri et al. [15]. In the present study, the Cronbach α coefficient for the EPDS was calculated at 0.70. The EPDS questionnaire was completed by both sets of parents, that is, those with healthy babies and those with CL/P babies who were referred to our center. The results from these two groups were then compared.

Statistical analysis

After completing the questionnaire, the collected information was categorized, entered into the SPSS software, version 21, and analyzed. Descriptive and demographic characteristics were presented as frequency distribution tables and graphs. The relationship between quantitative variables was analyzed by the t-test or its nonparametric equivalent if the data distribution was not normal. A significance level of 0.05% was considered in all calculations.

Results

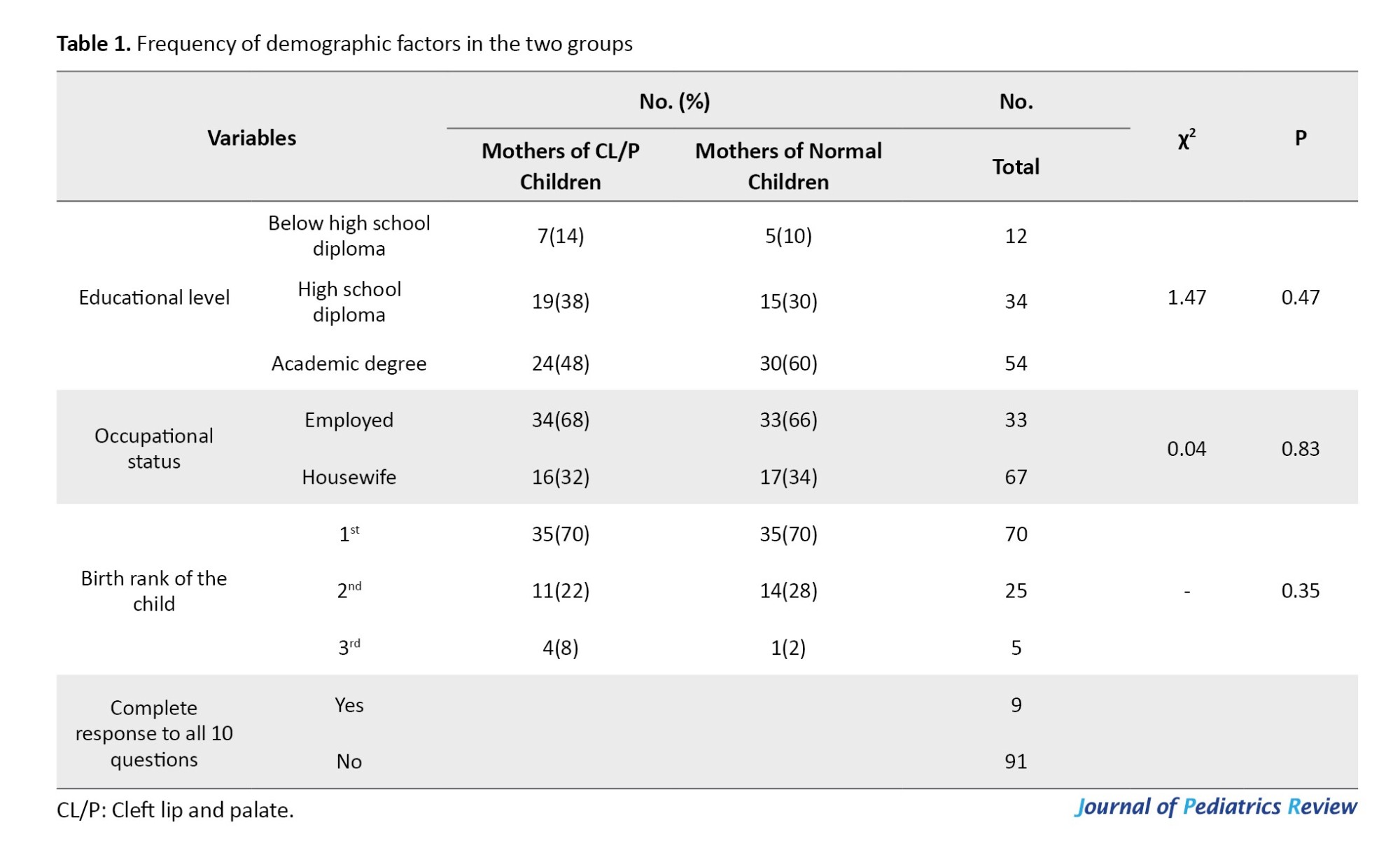

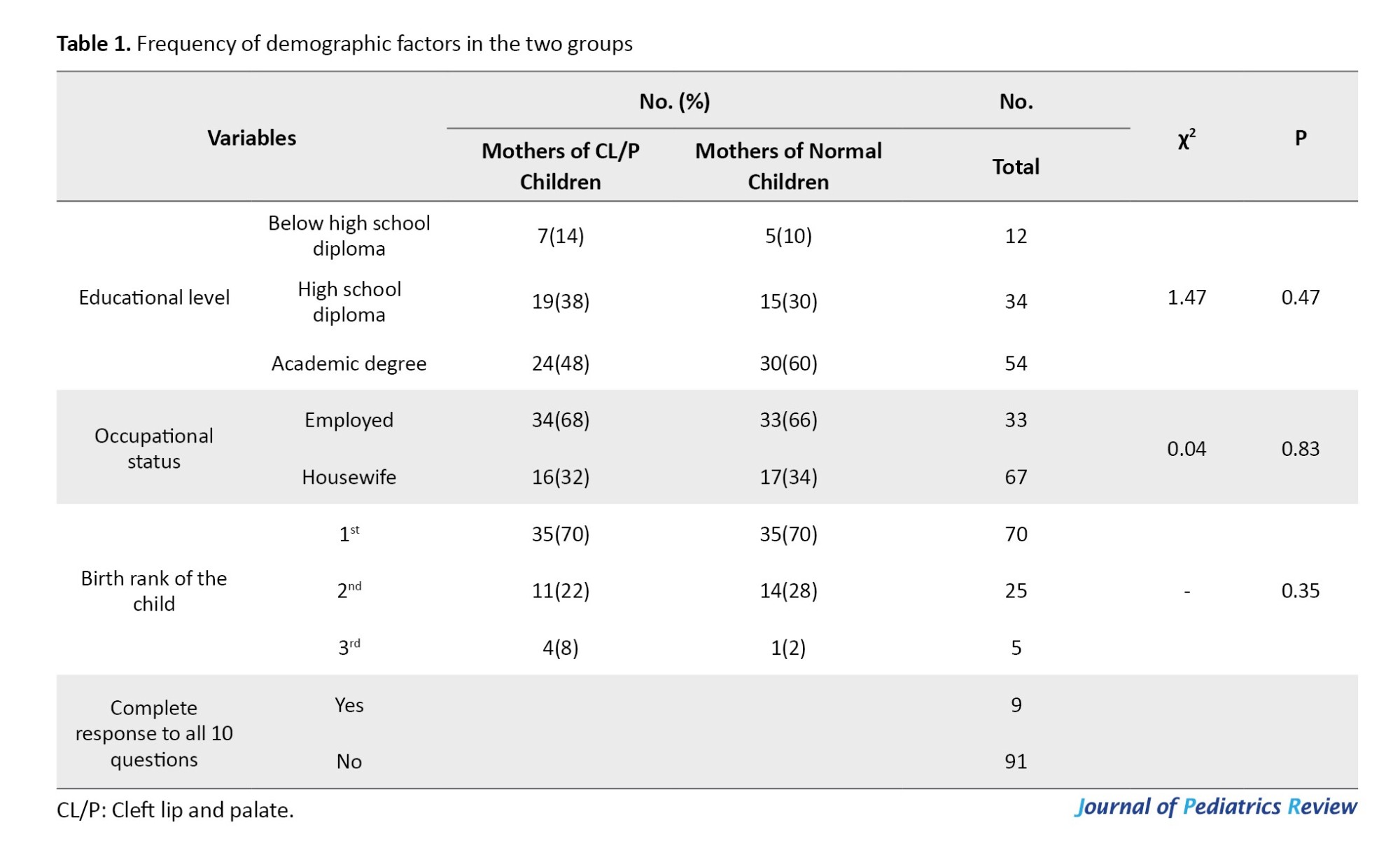

This study compared 50 mothers of children with CL/P with 50 mothers of normal children. The mean age of mothers was 27.49±6.1 years (range=15-38 years). The mean age was 27.66±5.94 years (range=18-38 years; median=29 years) in mothers of children with CL/P, and 27.32±6.32 years (range=15-38 years; median=29 years) in mothers of normal children. The two groups had no significant difference regarding the mean age (t=0.28, P=0.76). The frequency of other demographic characteristics is provided in Table 1. The mean PPD score was 12.86±6.33 (range=0-29).

The mean PPD score was 15.42±4.77 (range=5-24) in mothers of CL/P children, and 10.3±6.7 (range=0-29) in mothers of normal children after 2 to 4 weeks. A comparison of the two groups showed a significant difference in this regard (t=4.4, P<0.005). The mean PPD score was 15.42±4.77 (range=5-24) in mothers of CLP children, and 10.3±6.7 (range=0-29) in mothers of normal children after 2 to 4 weeks. A comparison of the two groups showed a significant difference in this regard (t=4.4, P<0.005). A comparison of PPD scores in terms of age, educational level, occupational status, and birth rank of the child is presented in Table 2. Based on the obtained results, the PPD score was not significantly correlated with age, educational level, occupational status, or birth rank of children (P>0.05).

Table 3 compares mothers with and without PPD in terms of having CL/P or normal children, their educational level, occupational status, and parity. A comparison of mothers with PPD and those without it showed that the frequency of PPD was significantly higher among mothers with CL/P children, compared with mothers of normal children (χ2=25.25, P<0.005). No significant difference was reported between mothers with PPD and those without it in terms of educational level (χ2=0.36, P=0.83) or occupational status (χ2=0.13, P=0.71). Moreover, there was no difference between mothers with PPD and those without PPD in terms of parity (P=0.93).

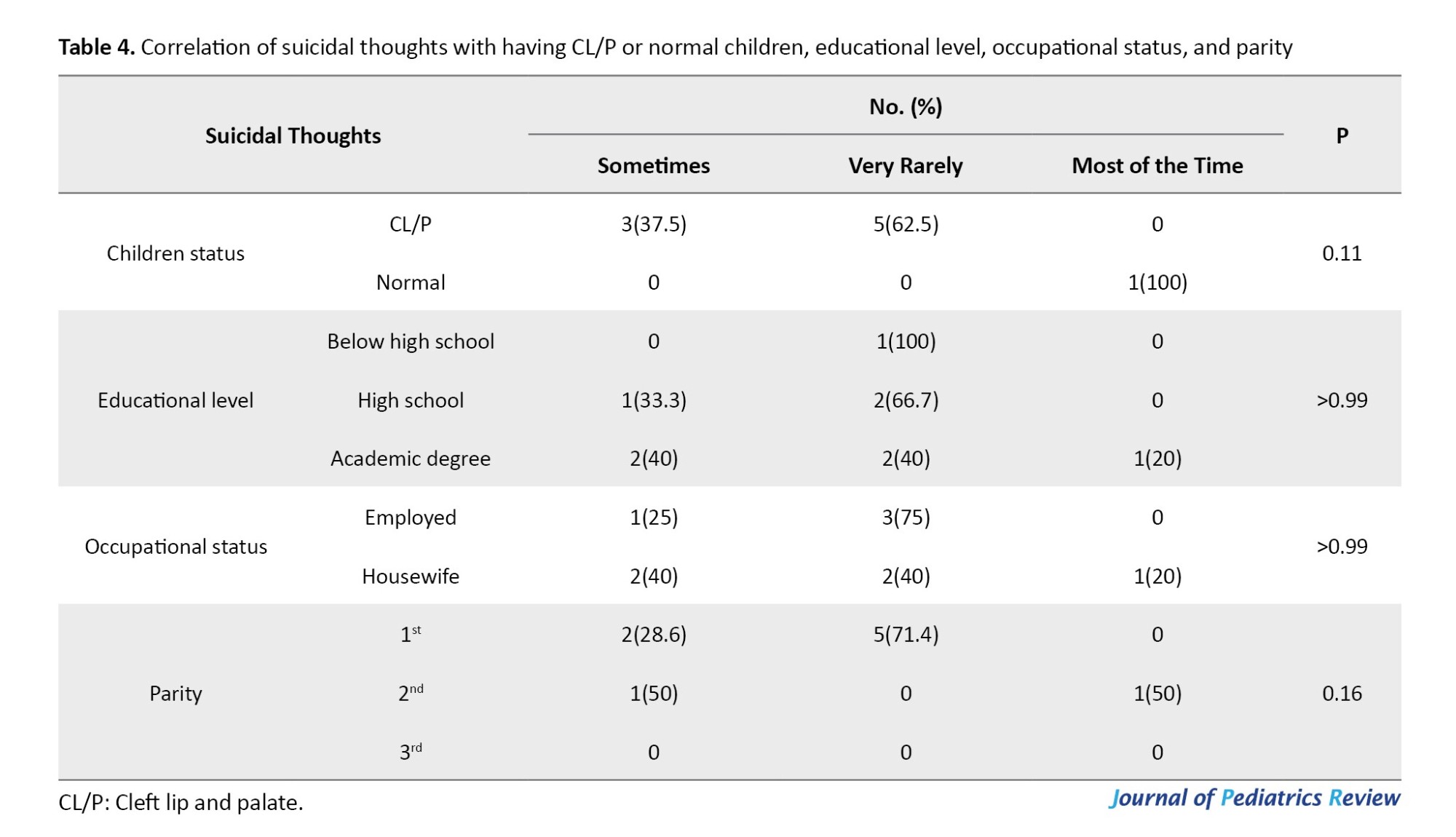

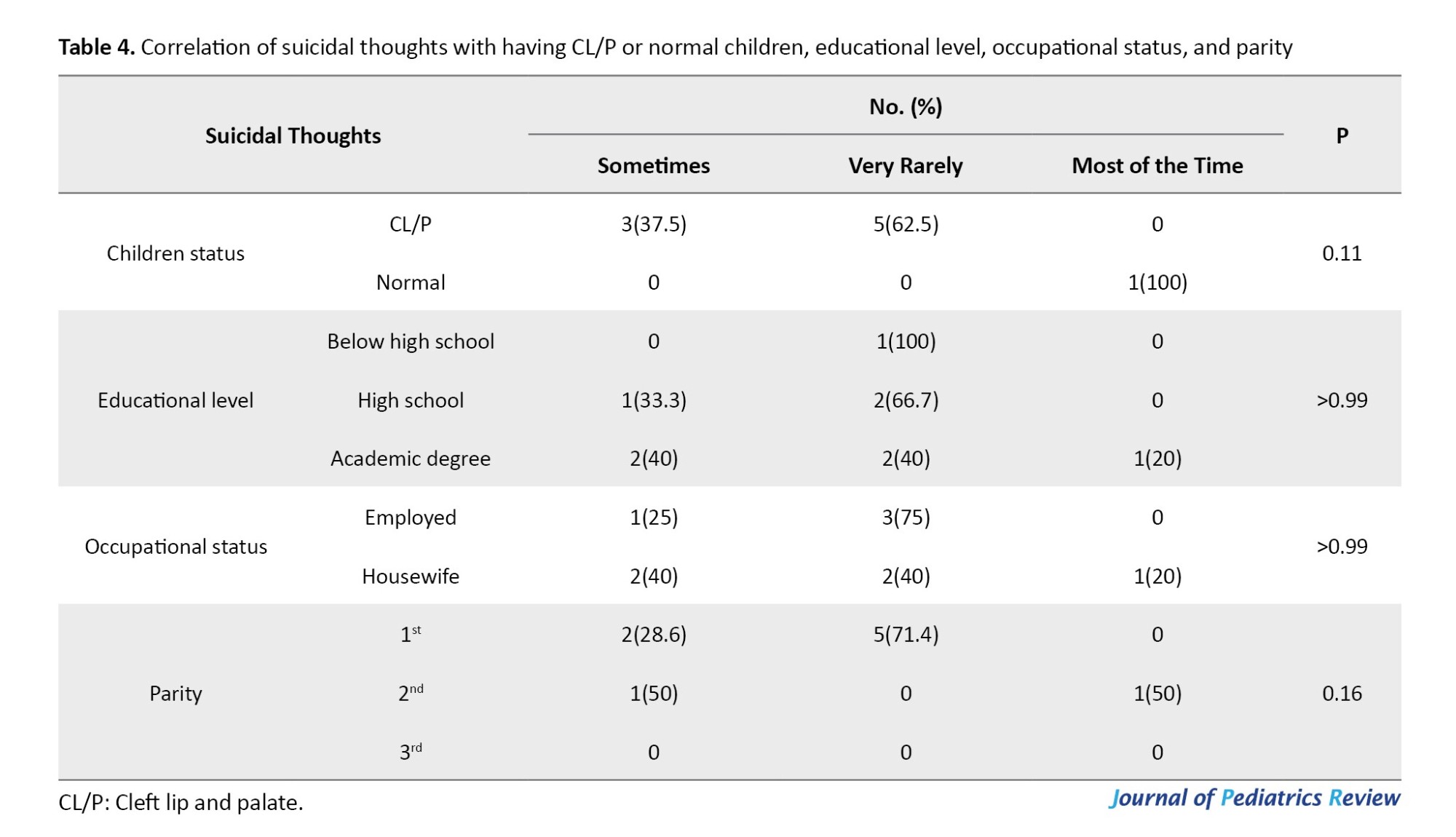

Table 4 shows the association of suicidal thoughts with having a CL/P or normal child, educational level, occupational status, and parity. Suicidal thoughts had no significant correlation with having a CL/P child (P=0.11). No significant difference was found between mothers with suicidal thoughts and those without suicidal thoughts in terms of educational level (P>0.99), occupational status (P>0.99), and parity (P=0.16).

Discussion

Based on the obtained results, the PPD score and frequency of PPD were higher among mothers of children with CL/P, compared with mothers of normal children; however, the frequency of suicidal thoughts was not significantly different between the two groups. Educational level, occupational status, and parity were not significantly different between mothers of children with CL/P, and mothers of normal children.

Detection of social withdrawal behaviors is of utmost importance, especially in the first months after delivery. Such behaviors should be treated promptly due to their association with the infant’s nutrition, especially in infants with a medical condition, as observed in children with CL/P [16]. in 2020, Grollemund et al. showed that children’s social withdrawal was not correlated with the severity of their cleft; however, it was associated with the stress and distress levels of their mothers [8]. Therefore, assessment of the psychological condition of mothers with CL/P infants and the related risk factors is highly important. Nevertheless, very few studies have evaluated the postpartum mental condition of mothers with CL/P infants.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the present study is the first to compare mothers of infants with CL/P and mothers of normal children regarding PPD and suicidal thoughts in Iran. Although no study has assessed the suicidal thoughts in mothers of children with CL/P, some studies have examined PPD in these mothers. One multicenter study by Grollemund et al. [8] assessed the effect of having a baby with CL/P on the parent-infant relationship. Based on the obtained results, the PPD scores were higher in parents (both mother and father) with CL/P infants, compared with the general population. Moreover, they found that maternal stress due to early intervention decreased at 4 months. Moreover, the waiting time between birth and the first surgical intervention was better accepted by parents who received a prenatal diagnosis [8]. Stock et al. assessed the parental psychological adjustment after detection of CL/P in their children, and showed higher levels of general anxiety and depression in mothers of CL/P children, compared with the general population. Moreover, a higher rate of perceived stress was reported in both parents of CL/P infants [17].

In a similar retrospective study by Johns et al. the PPD frequency and its risk factors in mothers of children with CL/P were assessed. They showed that 11.7% of mothers had PPD based on EPDS. Moreover, self-blame, difficulty coping, and feeling anxious were reported by more than 50% of them. Higher anxiety and incidence of feeling scared were reported in mothers who did not receive a prenatal diagnosis of CL/P. They reported that the lack of prenatal diagnosis and older maternal age were predictors for higher anxiety scores in mothers with CL/P infants. They reported a similar frequency of PPD among mothers with CL/P infants, compared with the general population [9].

However, in the present study, 40% of mothers of children with CL/P had PPD; whereas, this rate was 10% in mothers of normal children. This difference may reflect the role of social support in the incidence of PPD among mothers with CL/P infants. The study by Johns et al [9]. was conducted in the United States; however, the present study was performed in a developing country. Social support helps mothers adjust positively to stress-related growth and their infants’ condition [18]. However, social support for mothers of infants with CL/P is very low in developing countries. Moreover, insurance support is not sufficient to cover the treatment expenses of such infants. The frequency of PPD may be higher among mothers of children with CL/P in developing countries, compared with those living in developed countries, due to less availability of healthcare services, support, and insurance services in developing countries. However, John et al. showed no association between the type of health insurance and increased risk of PPD [18].

Screening for PPD is highly important in initial visits of mothers experiencing the symptoms of depression for additional support. Evidence shows that about 10% of symptoms of depression occur at the first meeting of mother and baby. In cases of prenatal diagnosis, although the mothers have high stress due to frequent medical visits, they may also benefit from continuous healthcare services and social support. The initial shock of having a CL/P infant could be decreased by prenatal diagnosis and counseling about the problem. Prenatal diagnosis provides the parents with a chance to adjust to the situation and become prepared for their child’s care [9]. It appears that prenatal diagnosis plays an important role in maternal PPD; therefore, screening and assessing the risk factors of CL/P are highly important for treatment planning. However, the effect of prenatal diagnosis was not evaluated in the present study.

Based on the results of a study by Johns et al, older mothers who did not receive a prenatal diagnosis had higher symptoms; moreover, in the general population, the risk of PPD was higher among younger mothers [9]. However, in the present study, mothers’ age was not correlated with PPD or suicidal thoughts. The effect of age on PPD should not be exaggerated since the role of age depends on other factors, such as unwanted pregnancy, financial problems, and being a single mother [19]. Moreover, the present study rejected the role of educational level, occupational status, and parity in the occurrence of PPD.

Future multi-center studies with a larger sample size are recommended to verify the present results. Further studies on psychosocial aspects of cleft care are also suggested to assess the efficacy of each type of support for mothers of children with CL/P.

Conclusion

According to the present results, PPD had a significantly higher prevalence among mothers with CL/P infants, compared with mothers of normal children. However, no difference was reported between them in terms of suicidal thoughts. Given the consequences of maternal depression on infant development, the present results highlight the necessity of psychological support for mothers with CL/P infants, especially during the first year of treatment of children.

Study strengths and limitations

Although the present findings paved the way for assessing the role of having CL/P infants in PPD, it faced some limitations. The small sample size and the single-center nature of the study limit the generalization of results to other populations. Furthermore, due to the self-reported nature of the data, the results might be affected by the mothers’ judgment. Moreover, the mothers’ ability and their comprehension might have affected the completion process of the questionnaire. Additionally, prenatal diagnosis and receipt of healthcare services by the mothers were not assessed in this study, which may affect the accuracy of the results.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MAZUMS.REC.1399.566). In this study, all ethical considerations were observed, and the information obtained through the questionnaires remained completely confidential. Furthermore, informed consent was obtained from all participants, and individuals who were suspected of PPD were referred to a psychiatrist for further assessment and treatment.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Maternal mental health is an important topic with a remarkable impact on children’s health and well-being. Depressed mothers may pay less attention to the health status of their children as a lower rate of referral for age-appropriate care for children and delays in vaccinations have been reported for infants with depressed mothers [1].

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a subtype of major depressive disorder and a serious mental health problem, the onset of which is during the first year after delivery. It commonly occurs within the first 3 months after birth [2]. PPD is experienced by 13% to 19% of childbearing women [3]. The incidence of PPD has been estimated at 11.5% in the United States [4]. Based on a systematic review, the prevalence of PPD is around 25.3% in Iran [5]. Assessment of the related factors to PDD is highly essential since it plays a fundamental role in maternal morbidity and mortality. Evidence confirms the correlation between fetal anomalies and mothers’ PPD scores [6].

Orofacial clefts are among the most common congenital anomalies that appear to affect the incidence of PDD. The mental health of mothers who have given birth to infants with cleft lip and or palate (CL/P) is a vital research topic [7]. One study found that nearly 12% of these mothers exhibited symptoms of depression, as measured by the Edinburgh postpartum depression Scale (EPDS). A significant proportion of these mothers reported self-blame (68.9%), difficulties in coping (59.2%), and feelings of anxiety (57.3%) [8]. Another study conducted in Turkey found that mothers of infants with a cleft experienced increased stress due to various factors, such as postnatal diagnosis, inability to breastfeed, feeding complications, lack of paternal support, perceived challenging infant temperament, feelings of blame and anger, and concerns about the future. These findings underscore the importance of providing comprehensive support and intervention for these mothers [9]. According to a previous study, the risk of depression 2 months after birth was higher among mothers of infants with CL/P, compared with mothers of normal infants [10]. However, limited studies have assessed the incidence of PDD in mothers of infants with CL/P.

Since some critical issues, such as the nutritional status of newborns in the early days after birth, may be affected by maternal mental conditions, assessment of the relationship between PPD and having an infant with CL/P is critical [7]. However, the majority of relevant available studies have focused on the stress level of mothers with CL/P children [11, 12]. Accordingly, this study compares the mothers of infants with CL/P and mothers of normal infants regarding PPD and suicidal thoughts.

Methods

This descriptive-analytical study was conducted on all mothers of children with CL/P, who had recently given birth and presented to the Research Center of Cranial Deformities, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran, from September 2020 to September 2021.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were having a child with CL/P, willingness to participate in the study, and referral at 2-4 weeks after delivery. Mothers taking antidepressants at the time of enrollment, those with a history of untreated prenatal depression, and those who refused to participate in the study were excluded.

Given the study’s objectives, the prevalence of CL/P in Iran (P=0.15) [13], and a confidence interval (CI) of 95%, the sample size was estimated to be approximately 45 cases using the Equation 1. However, to account for potential sample dropouts, the total number of samples was increased to 50. Additionally, 50 mothers with healthy children were included as the control group, resulting in a total of 100 samples examined.

Study design

A questionnaire was completed for each participant covering demographic characteristics, such as age, level of education, occupational status, parity, and history of PPD in previous pregnancy. After completing the questionnaire, the collected information was categorized. EPDS was filled out by a family health associate at a client health center. Each question in this 10-item scale was scored 0 to 3 based on the severity of signs and symptoms. This questionnaire was designed to assess the presence or absence of depression from 6 weeks postpartum afterward. Items 1, 2 and 4 are scored 0 to 3 and items 3 and 5-10, are scored 3 to 0. The items were rated using a 4-point Likert scale. The sum of all item scores was calculated and reported as the PPD score. The EPDS total score can range from 0 to 30, and a score above 12 indicates the presence of PPD. Higher scores indicate higher severity of PPD [14]. The validity and reliability of EPSD have been previously confirmed in Iran by Montazeri et al. [15]. In the present study, the Cronbach α coefficient for the EPDS was calculated at 0.70. The EPDS questionnaire was completed by both sets of parents, that is, those with healthy babies and those with CL/P babies who were referred to our center. The results from these two groups were then compared.

Statistical analysis

After completing the questionnaire, the collected information was categorized, entered into the SPSS software, version 21, and analyzed. Descriptive and demographic characteristics were presented as frequency distribution tables and graphs. The relationship between quantitative variables was analyzed by the t-test or its nonparametric equivalent if the data distribution was not normal. A significance level of 0.05% was considered in all calculations.

Results

This study compared 50 mothers of children with CL/P with 50 mothers of normal children. The mean age of mothers was 27.49±6.1 years (range=15-38 years). The mean age was 27.66±5.94 years (range=18-38 years; median=29 years) in mothers of children with CL/P, and 27.32±6.32 years (range=15-38 years; median=29 years) in mothers of normal children. The two groups had no significant difference regarding the mean age (t=0.28, P=0.76). The frequency of other demographic characteristics is provided in Table 1. The mean PPD score was 12.86±6.33 (range=0-29).

The mean PPD score was 15.42±4.77 (range=5-24) in mothers of CL/P children, and 10.3±6.7 (range=0-29) in mothers of normal children after 2 to 4 weeks. A comparison of the two groups showed a significant difference in this regard (t=4.4, P<0.005). The mean PPD score was 15.42±4.77 (range=5-24) in mothers of CLP children, and 10.3±6.7 (range=0-29) in mothers of normal children after 2 to 4 weeks. A comparison of the two groups showed a significant difference in this regard (t=4.4, P<0.005). A comparison of PPD scores in terms of age, educational level, occupational status, and birth rank of the child is presented in Table 2. Based on the obtained results, the PPD score was not significantly correlated with age, educational level, occupational status, or birth rank of children (P>0.05).

Table 3 compares mothers with and without PPD in terms of having CL/P or normal children, their educational level, occupational status, and parity. A comparison of mothers with PPD and those without it showed that the frequency of PPD was significantly higher among mothers with CL/P children, compared with mothers of normal children (χ2=25.25, P<0.005). No significant difference was reported between mothers with PPD and those without it in terms of educational level (χ2=0.36, P=0.83) or occupational status (χ2=0.13, P=0.71). Moreover, there was no difference between mothers with PPD and those without PPD in terms of parity (P=0.93).

Table 4 shows the association of suicidal thoughts with having a CL/P or normal child, educational level, occupational status, and parity. Suicidal thoughts had no significant correlation with having a CL/P child (P=0.11). No significant difference was found between mothers with suicidal thoughts and those without suicidal thoughts in terms of educational level (P>0.99), occupational status (P>0.99), and parity (P=0.16).

Discussion

Based on the obtained results, the PPD score and frequency of PPD were higher among mothers of children with CL/P, compared with mothers of normal children; however, the frequency of suicidal thoughts was not significantly different between the two groups. Educational level, occupational status, and parity were not significantly different between mothers of children with CL/P, and mothers of normal children.

Detection of social withdrawal behaviors is of utmost importance, especially in the first months after delivery. Such behaviors should be treated promptly due to their association with the infant’s nutrition, especially in infants with a medical condition, as observed in children with CL/P [16]. in 2020, Grollemund et al. showed that children’s social withdrawal was not correlated with the severity of their cleft; however, it was associated with the stress and distress levels of their mothers [8]. Therefore, assessment of the psychological condition of mothers with CL/P infants and the related risk factors is highly important. Nevertheless, very few studies have evaluated the postpartum mental condition of mothers with CL/P infants.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the present study is the first to compare mothers of infants with CL/P and mothers of normal children regarding PPD and suicidal thoughts in Iran. Although no study has assessed the suicidal thoughts in mothers of children with CL/P, some studies have examined PPD in these mothers. One multicenter study by Grollemund et al. [8] assessed the effect of having a baby with CL/P on the parent-infant relationship. Based on the obtained results, the PPD scores were higher in parents (both mother and father) with CL/P infants, compared with the general population. Moreover, they found that maternal stress due to early intervention decreased at 4 months. Moreover, the waiting time between birth and the first surgical intervention was better accepted by parents who received a prenatal diagnosis [8]. Stock et al. assessed the parental psychological adjustment after detection of CL/P in their children, and showed higher levels of general anxiety and depression in mothers of CL/P children, compared with the general population. Moreover, a higher rate of perceived stress was reported in both parents of CL/P infants [17].

In a similar retrospective study by Johns et al. the PPD frequency and its risk factors in mothers of children with CL/P were assessed. They showed that 11.7% of mothers had PPD based on EPDS. Moreover, self-blame, difficulty coping, and feeling anxious were reported by more than 50% of them. Higher anxiety and incidence of feeling scared were reported in mothers who did not receive a prenatal diagnosis of CL/P. They reported that the lack of prenatal diagnosis and older maternal age were predictors for higher anxiety scores in mothers with CL/P infants. They reported a similar frequency of PPD among mothers with CL/P infants, compared with the general population [9].

However, in the present study, 40% of mothers of children with CL/P had PPD; whereas, this rate was 10% in mothers of normal children. This difference may reflect the role of social support in the incidence of PPD among mothers with CL/P infants. The study by Johns et al [9]. was conducted in the United States; however, the present study was performed in a developing country. Social support helps mothers adjust positively to stress-related growth and their infants’ condition [18]. However, social support for mothers of infants with CL/P is very low in developing countries. Moreover, insurance support is not sufficient to cover the treatment expenses of such infants. The frequency of PPD may be higher among mothers of children with CL/P in developing countries, compared with those living in developed countries, due to less availability of healthcare services, support, and insurance services in developing countries. However, John et al. showed no association between the type of health insurance and increased risk of PPD [18].

Screening for PPD is highly important in initial visits of mothers experiencing the symptoms of depression for additional support. Evidence shows that about 10% of symptoms of depression occur at the first meeting of mother and baby. In cases of prenatal diagnosis, although the mothers have high stress due to frequent medical visits, they may also benefit from continuous healthcare services and social support. The initial shock of having a CL/P infant could be decreased by prenatal diagnosis and counseling about the problem. Prenatal diagnosis provides the parents with a chance to adjust to the situation and become prepared for their child’s care [9]. It appears that prenatal diagnosis plays an important role in maternal PPD; therefore, screening and assessing the risk factors of CL/P are highly important for treatment planning. However, the effect of prenatal diagnosis was not evaluated in the present study.

Based on the results of a study by Johns et al, older mothers who did not receive a prenatal diagnosis had higher symptoms; moreover, in the general population, the risk of PPD was higher among younger mothers [9]. However, in the present study, mothers’ age was not correlated with PPD or suicidal thoughts. The effect of age on PPD should not be exaggerated since the role of age depends on other factors, such as unwanted pregnancy, financial problems, and being a single mother [19]. Moreover, the present study rejected the role of educational level, occupational status, and parity in the occurrence of PPD.

Future multi-center studies with a larger sample size are recommended to verify the present results. Further studies on psychosocial aspects of cleft care are also suggested to assess the efficacy of each type of support for mothers of children with CL/P.

Conclusion

According to the present results, PPD had a significantly higher prevalence among mothers with CL/P infants, compared with mothers of normal children. However, no difference was reported between them in terms of suicidal thoughts. Given the consequences of maternal depression on infant development, the present results highlight the necessity of psychological support for mothers with CL/P infants, especially during the first year of treatment of children.

Study strengths and limitations

Although the present findings paved the way for assessing the role of having CL/P infants in PPD, it faced some limitations. The small sample size and the single-center nature of the study limit the generalization of results to other populations. Furthermore, due to the self-reported nature of the data, the results might be affected by the mothers’ judgment. Moreover, the mothers’ ability and their comprehension might have affected the completion process of the questionnaire. Additionally, prenatal diagnosis and receipt of healthcare services by the mothers were not assessed in this study, which may affect the accuracy of the results.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MAZUMS.REC.1399.566). In this study, all ethical considerations were observed, and the information obtained through the questionnaires remained completely confidential. Furthermore, informed consent was obtained from all participants, and individuals who were suspected of PPD were referred to a psychiatrist for further assessment and treatment.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Minkovitz CS, Strobino D, Scharfstein D, Hou W, Miller T, Mistry KB, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms and children’s receipt of health care in the first 3 years of life. Pediatrics. 2005; 115(2):306-14. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2004-0341] [PMID]

- Field T. Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: A review. Infant Behav Dev. 2010; 33(1):1-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.005] [PMID]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Committee on Obstetric Practice. The Apgar score. Adv Neonatal Care. 2006; 6:220-3. [Link]

- Ko JY, Rockhill KM, Tong VT, Morrow B, Farr SL. Trends in postpartum depressive symptoms-27 states, 2004, 2008, and 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017; 66(6):153-8. [DOI:10.15585/mmwr.mm6606a1] [PMID]

- Veisani Y, Delpisheh A, Sayehmiri K, Rezaeian S. Trends of postpartum depression in iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Res Treat. 2013; 2013 :291029. [DOI:10.1155/2013/291029] [PMID]

- Kim AJH, Servino L, Bircher S, Feist C, Rdesinski RE, Dukhovny S, et al. Depression and socioeconomic stressors in expectant parents with fetal congenital anomalies. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021; 35(25):8645-51. [DOI:10.1080/14767058.2021.1992379] [PMID]

- Parker SE, Mai CT, Canfield MA, Rickard R, Wang Y, Meyer RE, et al. Updated national birth prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004-2006. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010; 88(12):1008-16. [DOI:10.1002/bdra.20735] [PMID]

- Grollemund B, Dissaux C, Gavelle P, Martínez CP, Mullaert J, Alfaiate T, et al. The impact of having a baby with cleft lip and palate on parents and on parent-baby relationship: The first French prospective multicentre study. BMC Pediatr. 2020; 20(1):230. [DOI:10.1186/s12887-020-02118-5] [PMID]

- Johns AL, Hershfield JA, Seifu NM, Haynes KA. Postpartum depression in mothers of infants with cleft lip and/or palate. J Craniofac Surg. 2018; 29(4):e354-8. [DOI:10.1097/SCS.0000000000004319] [PMID]

- Murray L, Hentges F, Hill J, Karpf J, Mistry B, Kreutz M, et al. The effect of cleft lip and palate, and the timing of lip repair on mother-infant interactions and infant development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008; 49(2):115-23. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01833.x] [PMID]

- Despars J, Peter C, Borghini A, Pierrehumbert B, Habersaat S, Müller-Nix C, et al. Impact of a cleft lip and/or palate on maternal stress and attachment representations. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2011; 48(4):419-24. [DOI:10.1597/08-190] [PMID]

- Boztepe H, Çınar S, Özgür Md FF. Parenting stress in Turkish mothers of infants with cleft lip and/or palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2020; 57(6):753-61. [DOI:10.1177/1055665619898592] [PMID]

- Namdar P, Etezadi T, Mousavi SJ, Maleknia A, Shiva A. Frequency of cleft lip with or without cleft palate and related factors in a group of neonates in three Hospitals in Sari, Iran, during 2004-2018. J Mashhad Dental School. 2021; 45(2):178-87. [DOI:10.22038/jmds.2021.50128.1943]

- Levis B, Negeri Z, Sun Y, Benedetti A, Thombs BD; DEPRESsion Screening Data (DEPRESSD) EPDS Group. Accuracy of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for screening to detect major depression among pregnant and postpartum women: Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2020; 371:m4022. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.m4022] [PMID]

- Montazeri A, Torkan B, Omidvari S. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. BMC Psychiatry. 2007; 7:11. [DOI:10.1186/1471-244X-7-11] [PMID]

- Re JM, Dean S, Mullaert J, Guedeney A, Menahem S. Maternal distress and infant social withdrawal (ADBB) following infant cardiac surgery for congenital heart disease. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2018; 9(6):624-37. [DOI:10.1177/2150135118788788] [PMID]

- Stock NM, Costa B, White P, Rumsey N. Risk and protective factors for psychological distress in families following a diagnosis of cleft lip and/or palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2020; 57(1):88-98. [DOI:10.1177/1055665619862457] [PMID]

- Baker SR, Owens J, Stern M, Willmot D. Coping strategies and social support in the family impact of cleft lip and palate and parents' adjustment and psychological distress. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2009; 46(3):229-36. [DOI:10.1597/08-075.1] [PMID]

- Rich-Edwards JW, Kleinman K, Abrams A, Harlow BL, McLaughlin TJ, Joffe H, et al. Sociodemographic predictors of antenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms among women in a medical group practice. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006; 60(3):221-7. [DOI:10.1136/jech.2005.039370] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Psychiatry

Received: 2023/09/9 | Accepted: 2023/12/25 | Published: 2024/01/1

Received: 2023/09/9 | Accepted: 2023/12/25 | Published: 2024/01/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |