Volume 12, Issue 1 (1-2024)

J. Pediatr. Rev 2024, 12(1): 41-52 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Nematian F, Edalattalab F. Iranian Adolescent Girls’ Related-anxiety Factors During and Post-COVID-19: A Systematic Review Study. J. Pediatr. Rev 2024; 12 (1) :41-52

URL: http://jpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-588-en.html

URL: http://jpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-588-en.html

1- Department of Anesthesiology, Faculty of Allied Medical Sciences, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran. , nematian7074@gmail.com

2- Department of Operating Room, Faculty of Paramedical Sciences, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran.

2- Department of Operating Room, Faculty of Paramedical Sciences, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 534 kb]

(900 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2066 Views)

Full-Text: (852 Views)

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a global pandemic on March 11, 2020 [1]. This declaration precipitated a myriad of psychological, physical, and social challenges worldwide [2]. As a pivotal measure to mitigate the rampant spread of the disease, governments worldwide resorted to widespread school closures [3]. Surveys conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic underscored the profound impact of school closures and home quarantine on the physical and mental well-being of adolescents [4]. During periods of school closure, adolescents exhibited reduced physical activity levels, disrupted sleep patterns, and inadequate dietary habits [4]. The pandemic and associated school closures imposed a range of adverse outcomes, including diminished physical activity, feelings of confinement, fear of contagion, social isolation from peers, academic challenges, and increased familial tension [5], Consequently, adolescents experienced heightened levels of anxiety stemming from COVID-19, leading to various maladaptive behaviors, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, anorexia nervosa, and depression [6, 7].

A study conducted by Liang et al. (2020) comprising 548 adolescent students during quarantine revealed that 40% of them exhibited mental health issues, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and psychological distress [8]. Consequently, the COVID-19 outbreak poses significant psychological stressors, potentially detrimental to students’ learning and mental well-being [9].

Furthermore, reviews of studies conducted globally have highlighted the adverse psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond its mortality, with anxiety being a predominant issue [10]. Anxiety is characterized by heightened worry and agitation concerning potential future adversities [11]. Specifically, coronavirus anxiety arises from the uncertainties surrounding the COVID-19 infection, fostering cognitive ambiguity [12]. Zhang et al.’s investigation into anxiety prevalence among students during the COVID-19 outbreak reported a prevalence rate of 31.4% [13], underscoring the vulnerability of adolescents during this period of heightened stress and anxiety [14].

The elevated stress and anxiety experienced during quarantine and social isolation, compounded by the absence of peer interaction, contribute significantly to adolescents’ psychological distress [15, 16]. Notably, research by Cerván-Lavigne et al. demonstrated that girls experienced higher levels of anxiety compared to boys amidst the COVID-19 pandemic [17]. The abrupt transition to virtual learning and the unprecedented experience of a pandemic outbreak further exacerbated fear and stress among adolescents [18, 19].

Fear, defined as the response to an imminent threat or dangerous circumstances, is a prevalent emotion during the COVID-19 pandemic [20]. Studies indicate that fear of illness and death, coupled with disruptions to daily routines, can detrimentally affect adolescents’ psychological well-being, contributing to increased anxiety and depression [21]. In a pandemic, such as the coronavirus, fear of illness and fear of death combined with the disruption of daily activities causes people to struggle with disease anxiety [22]. Pandemic viral infections can cause significant mental distress at the population level [23].

Given the pivotal role of adolescent girls in shaping future societal dynamics and the critical developmental stage of adolescence, particularly amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, identifying factors contributing to anxiety and fear in adolescent girls during both the pandemic and post-pandemic periods is imperative. The insights gleaned from this study hold promise for formulating preventive measures and interventions to mitigate mental health challenges and disorders among adolescent girls.

Methods

This is a systematic review study to explore factors associated with anxiety and fear among adolescent girls during the COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 periods in Iran. The research population comprises all scientific articles indexed in reputable databases that address this topic. The search encompassed international databases, such as PubMed, Science Direct, and Google Scholar, as well as Persian language databases, including the Scientific Information Database (SID). No time constraints were applied to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant literature. To find related articles in English language databases, we used the following keywords: “Anxiety,” “fear,” “phobia,” “adolescent,” “teenager,” “teener,” “coronavirus,” “corona,” and “COVID-19.” The keywords were used in combination via AND/OR mediators. The search strategy in the PubMed database was based on the following combination:

(Anxiety OR fear OR phobia) AND (adolescent OR teenager OR teener) AND (coronavirus OR corona OR COVID-19).

The keywords used to search in Persian databases included the combination of the words “anxiety,” “fear,” “youth,” “coronavirus,” and “COVID-19,” in multiples. Paper sources were not used because the articles published in the mentioned databases are more valid than theses that have not been written and access to internet resources is more possible than books and theses.

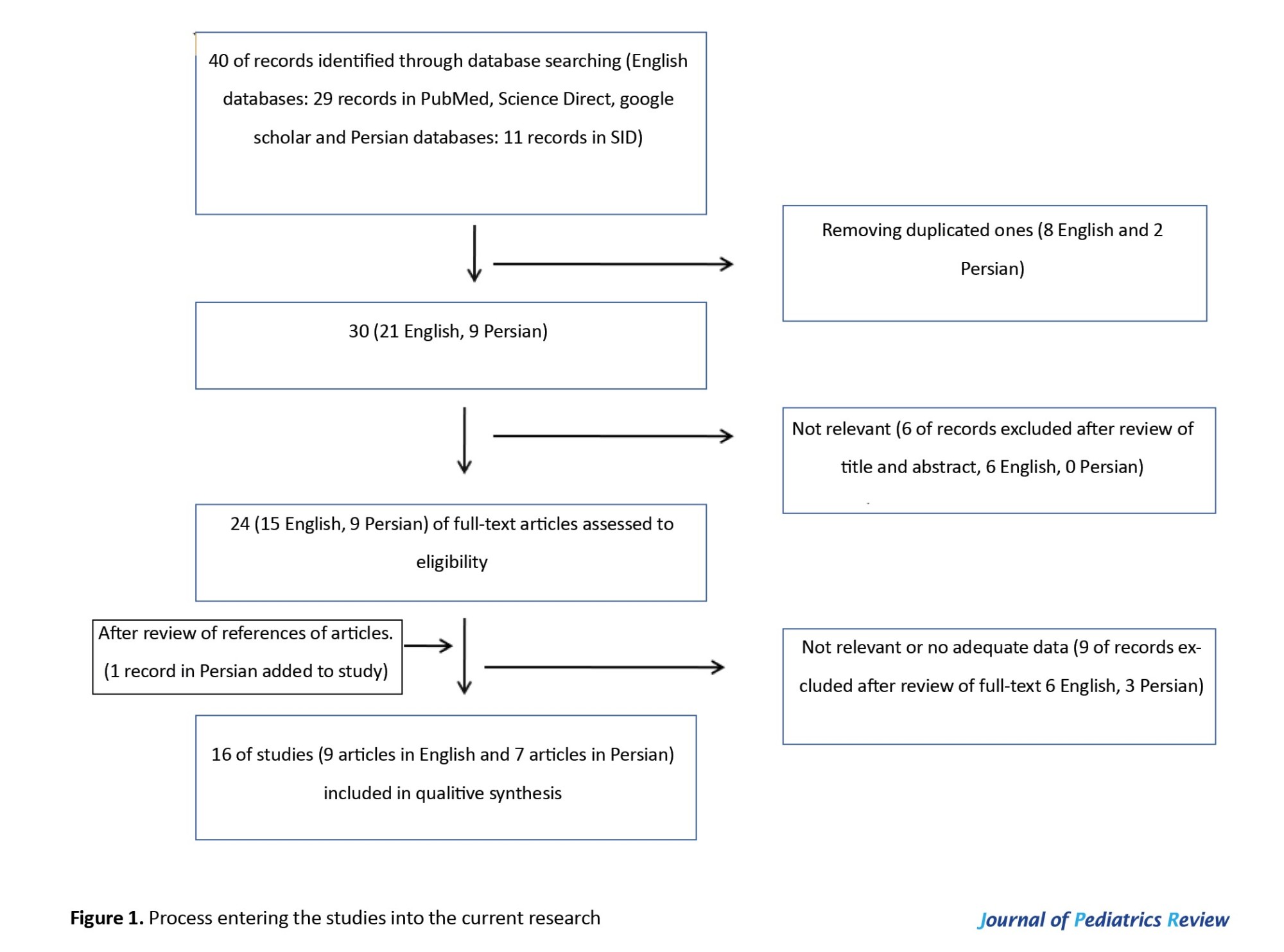

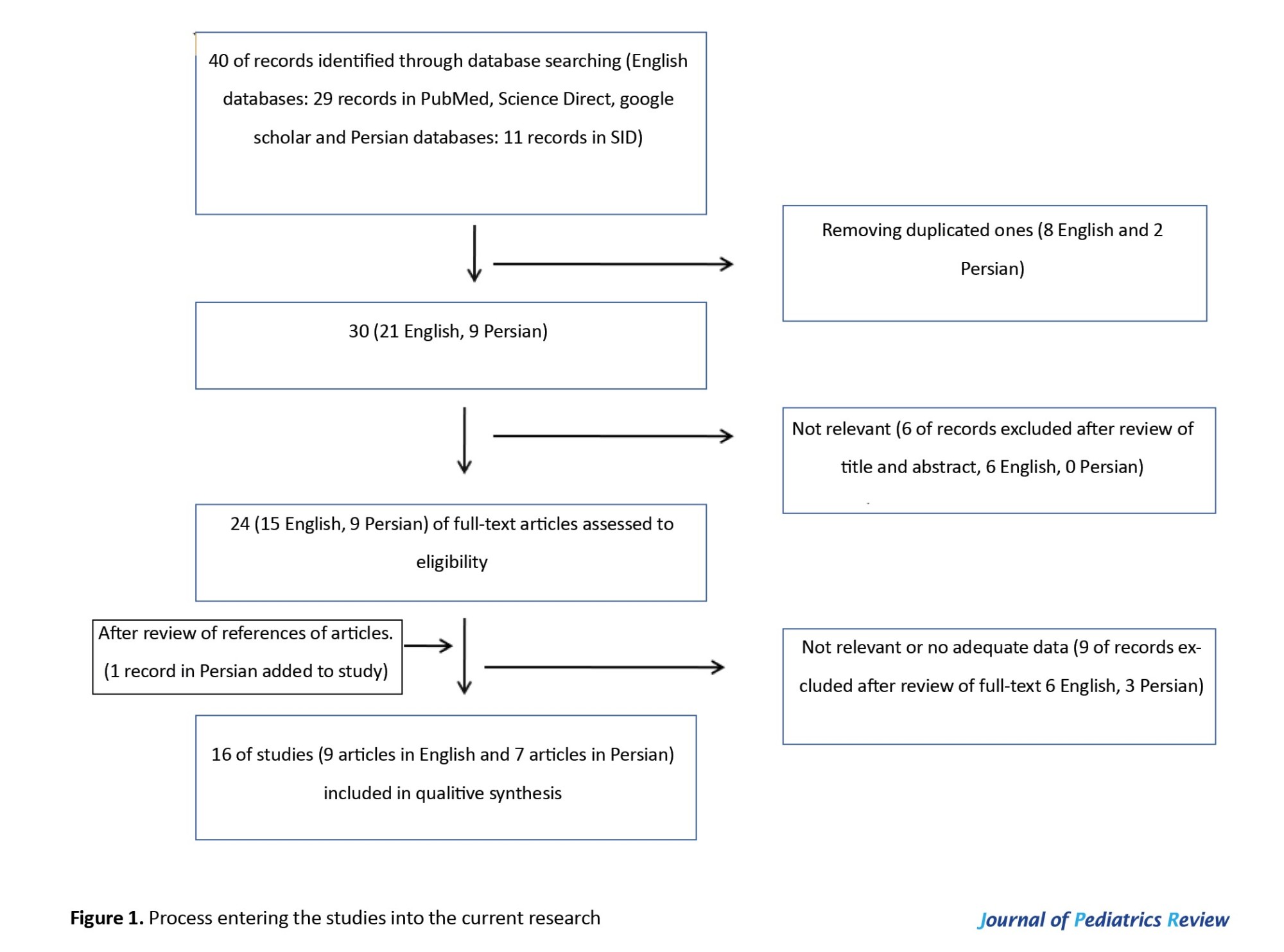

After searching, 19328 studies were obtained. Endnote information resource management software was used to organize the studies. At first, 18883 unrelated studies were removed by reviewing the titles of the articles. Subsequently, using the aforementioned software, and by reviewing the titles of the articles, 454 related studies were found, which were examined by the researchers by reviewing the abstracts of 40 articles. The process of entering studies into research is shown in Figure 1. The Inclusion criteria were published articles in Persian or English, conducting research in Iran, females as the target population of the article, having access to the full text of the articles, original research papers (including descriptive articles), and mentioning factors affecting anxiety. Meanwhile, review articles and letters to the editor were not selected due to a lack of primary data.

By carefully studying the title and abstract of the articles that met the inclusion criteria by the researcher, a large number of the articles were eliminated due to their weak connection with the purpose of the study. If it was not possible to decide on the article after reading the title and abstract, the authors referred to the full text. Then, to ensure the recovery of all the documents, the list of sources of articles was also searched and a qualified study was added to the analysis. Several articles were excluded due to the disproportionate age range of samples and some due to a lack of investigation of anxiety factors or relation with the COVID-19 period.

After examining the purpose of the studies and inclusion criteria, 16 studies were evaluated in terms of quality by two researchers separately. The quality of these articles was evaluated using the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) scale. This scale evaluates the articles in terms of the selection process, including representativeness of samples, sample size, location and time of the study, sampling process, description of study design, inclusion, and exclusion criteria, definition of study variables, and description of tools, and examines the results (statistical analysis, demographic characteristics, and study results). Based on the STROBE scale, the articles are scored from 0 (the weakest) to 18 (the strongest). To preserve the data, the studies that had a score lower than the average score (<9) were considered low quality.

Results

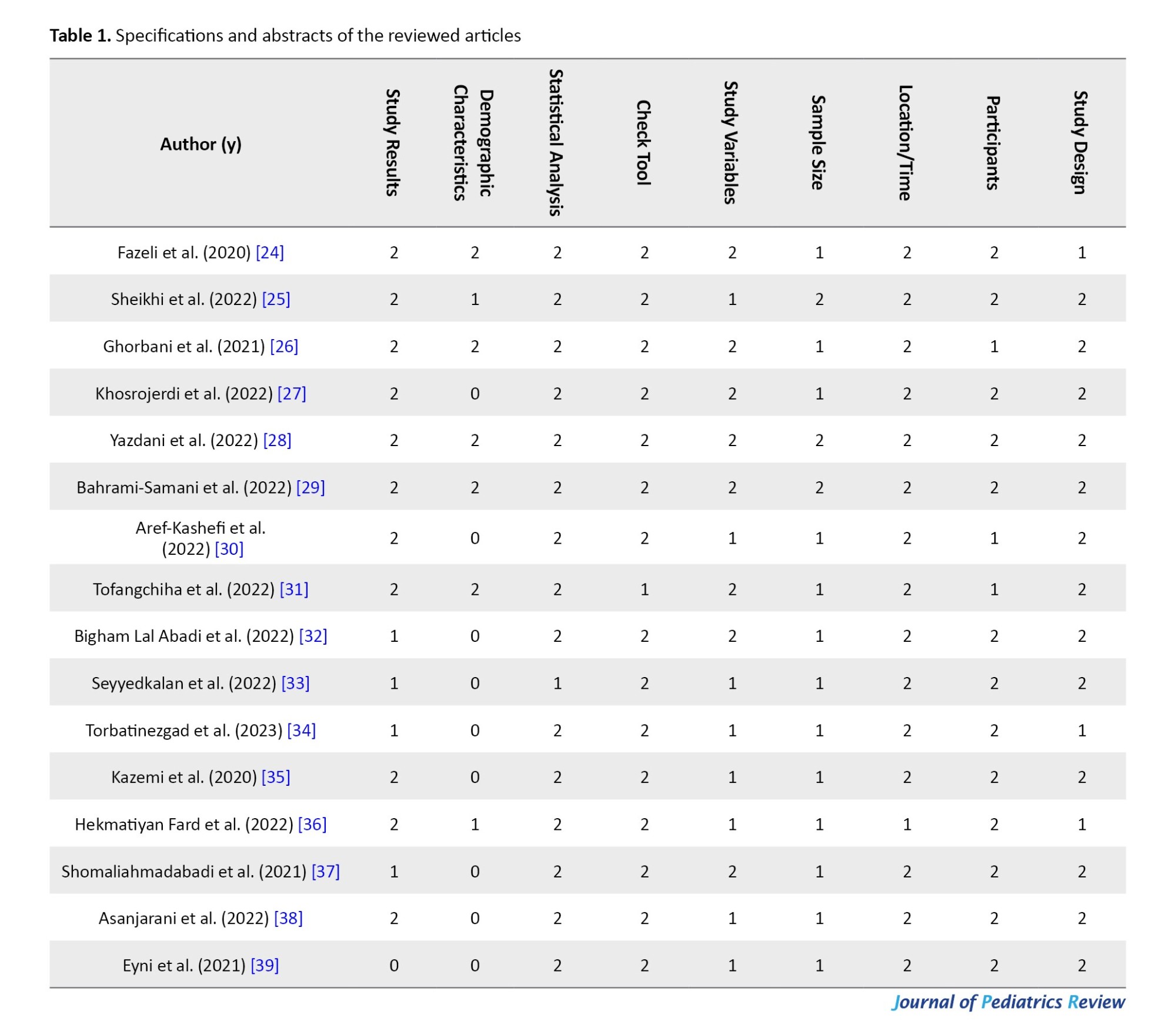

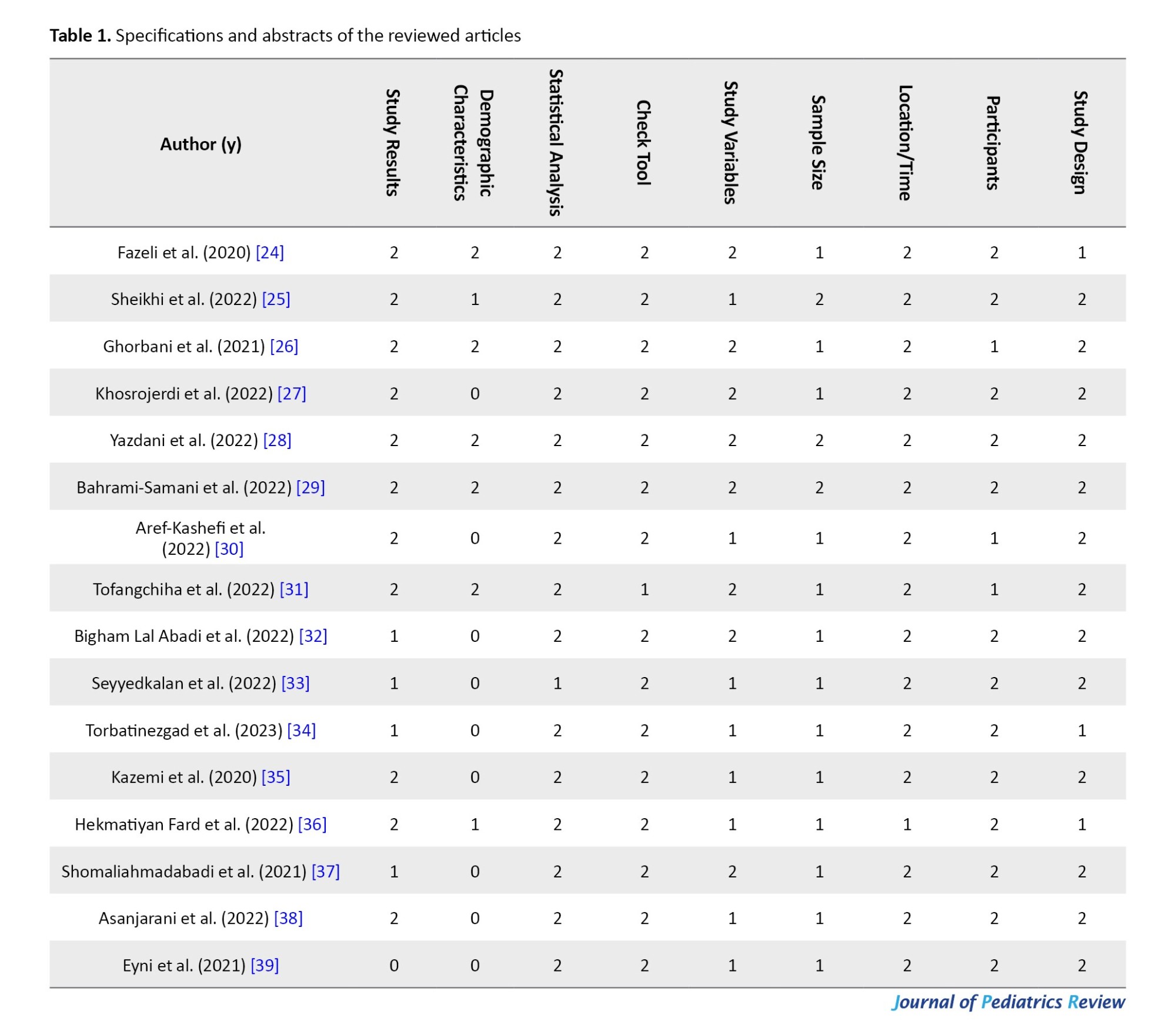

In this study, a total of 16 eligible papers were systematically reviewed. The articles underwent rigorous evaluation using the STROBE checklist, as depicted in Table 1.

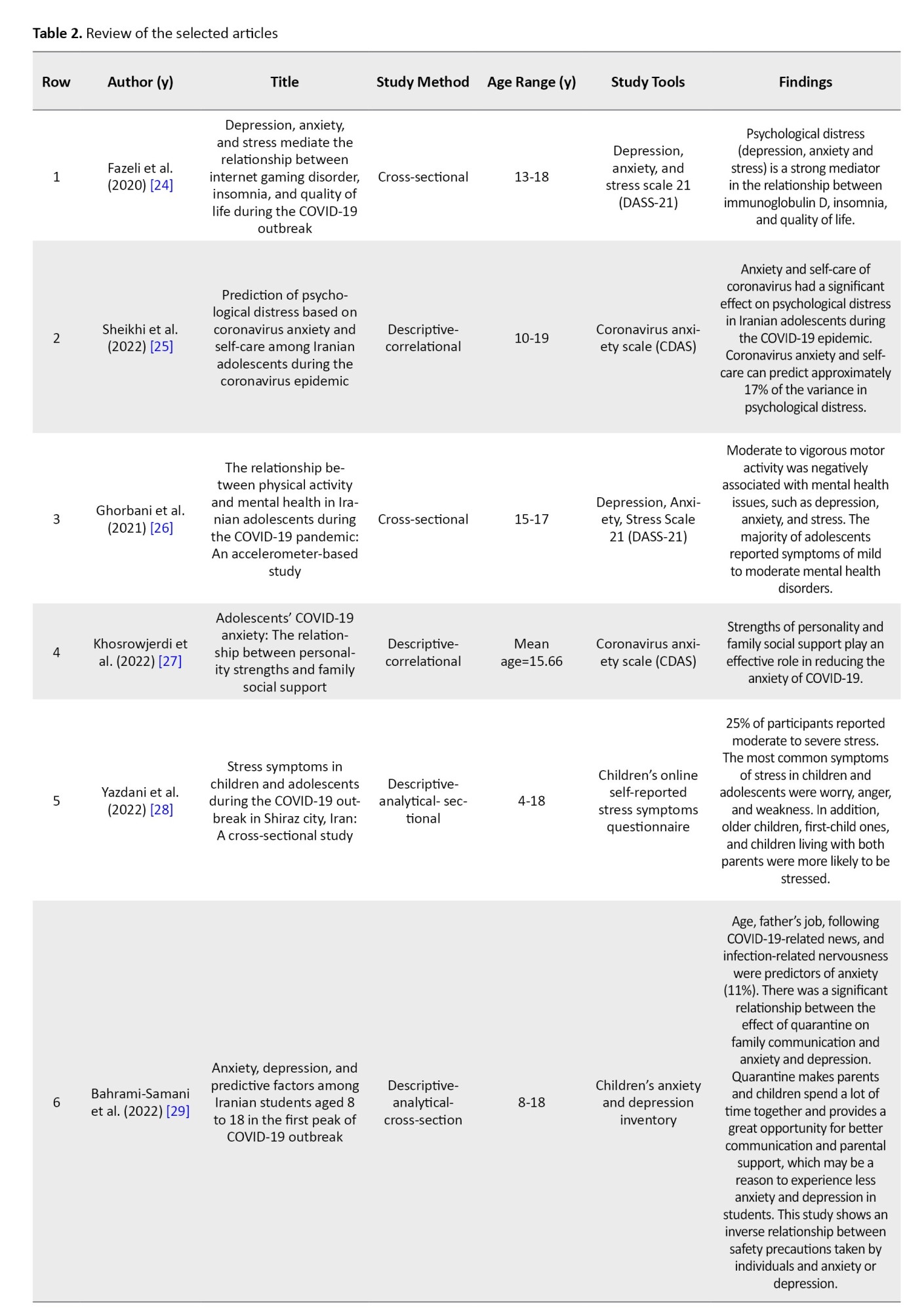

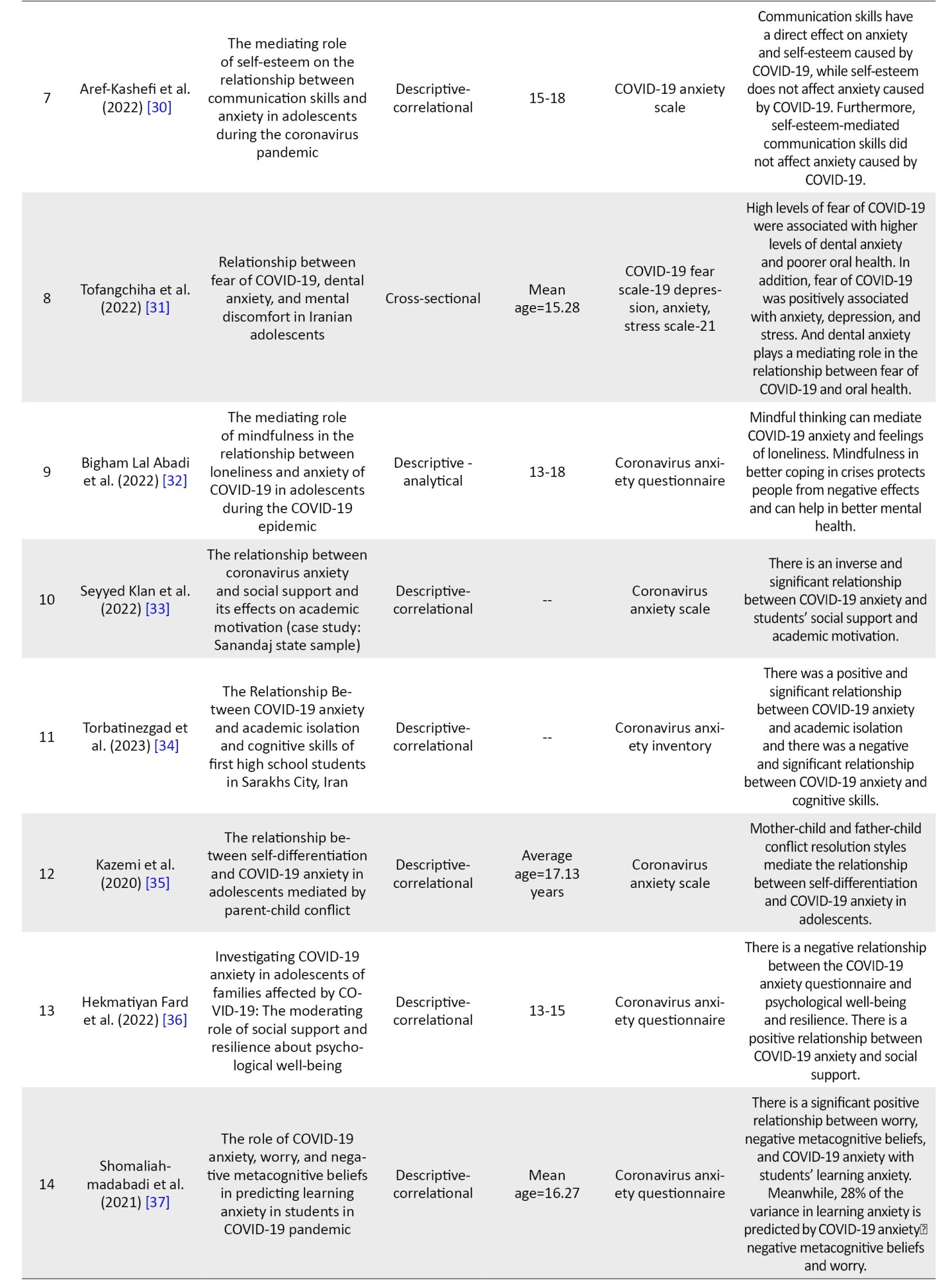

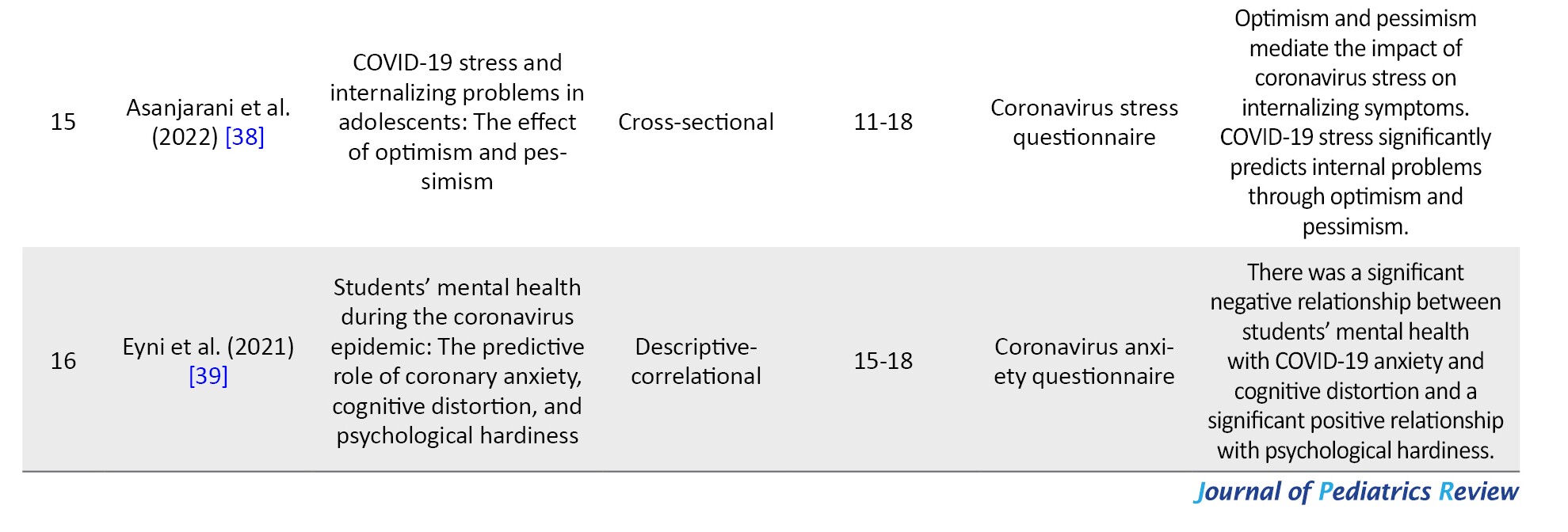

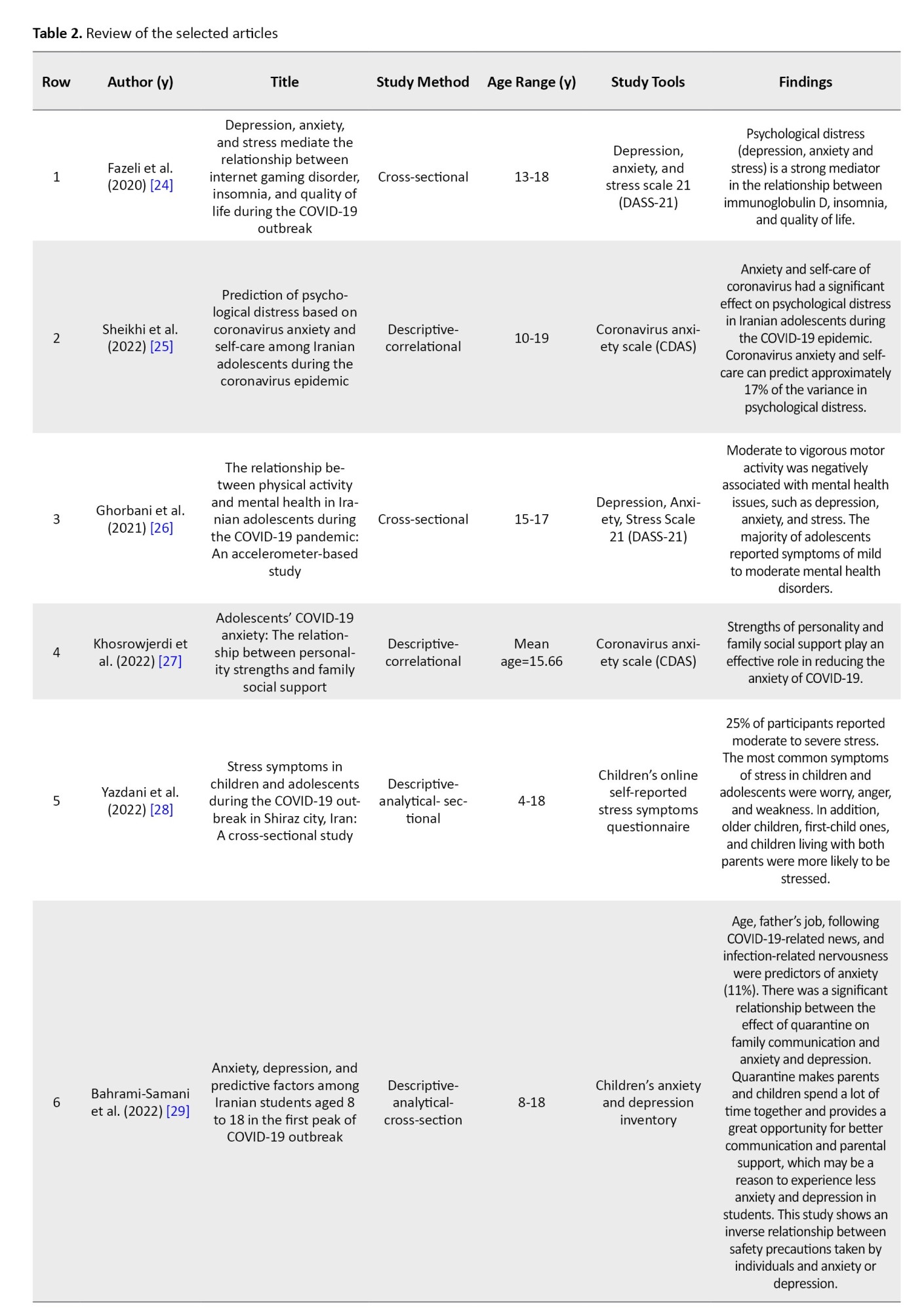

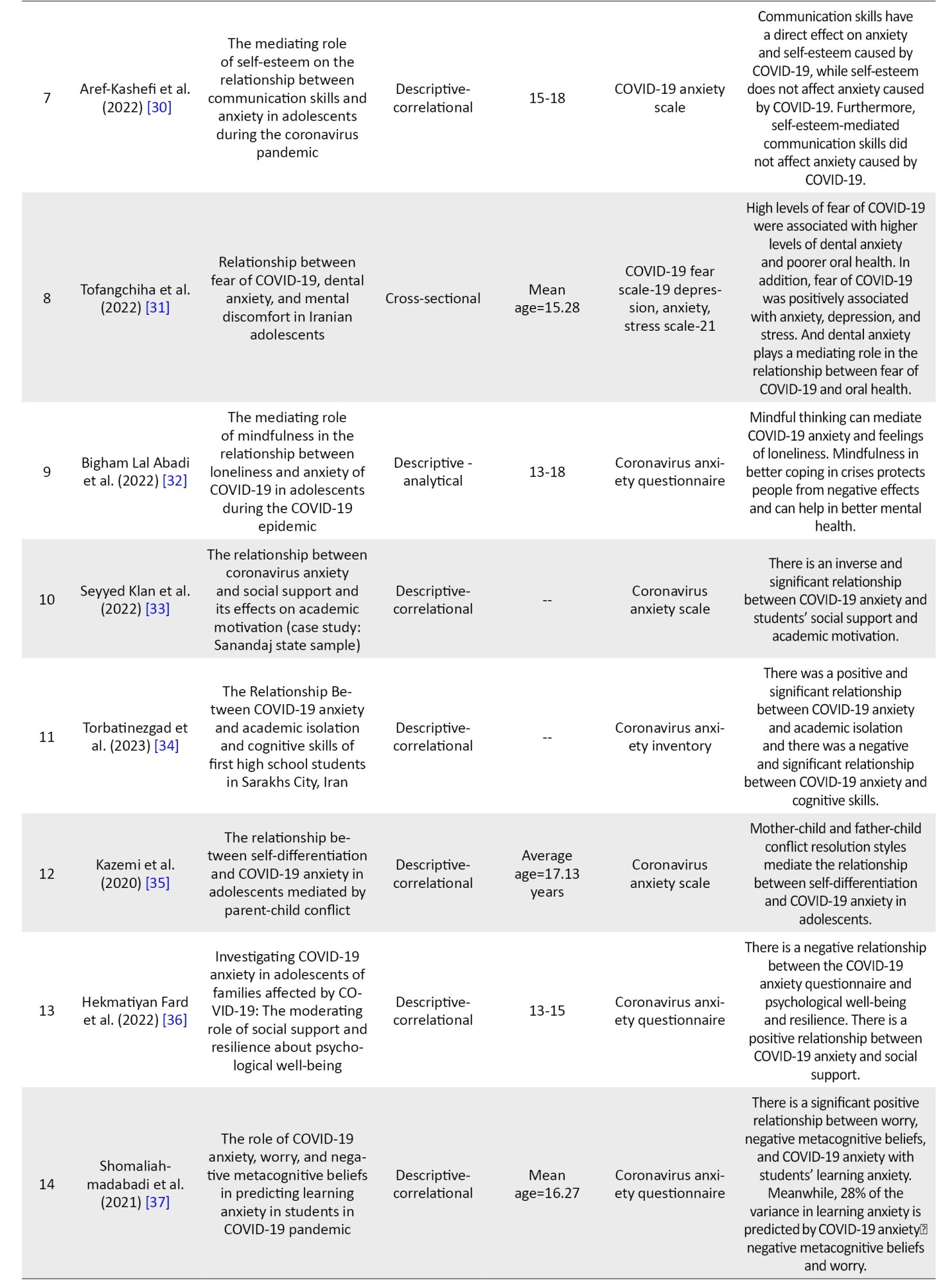

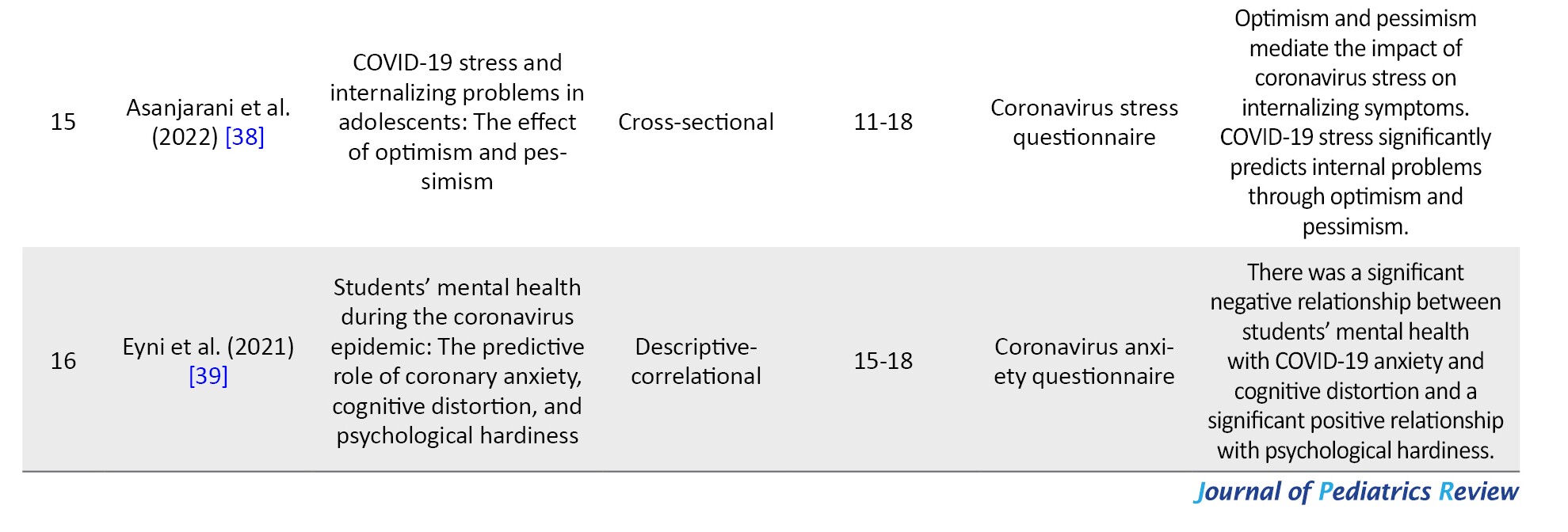

The findings extracted from the reviewed articles about anxiety and fear among adolescent girls during both the COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 periods are synthesized and presented in Table 2.

Discussion

The current research discerned the factors associated with anxiety and fear among adolescent girls during the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath. The study findings revealed a notable prevalence of anxiety among teenagers amid the COVID-19 outbreak. Factors contributing to this phenomenon include the developmental stage of adolescence, paternal occupation, limited knowledge about the disease, apprehension stemming from its unknown nature, diminished parental support, prolonged periods of quarantine, restricted autonomy of teenagers, and reduced social interactions with peers.

The limited scientific knowledge surrounding the coronavirus has a significant impact on adolescent girls [40], who are more susceptible, which exacerbates their anxiety. The prevailing uncertainty and cognitive ambiguity associated with this virus contribute to widespread anxiety among teenagers. Fear of the unknown has historically been a catalyst for anxiety across human societies. Presently, the escalation of mental distress attributed to the proliferation of infectious diseases within society notably amplifies fear and anxiety levels. COVID-19 anxiety manifests as a physiological and psychological response when individuals perceive an imbalance between their capabilities and the demands imposed by the pandemic. This imbalance during the era of COVID-19 anxiety detrimentally affects adolescents’ learning outcomes [34]. According to Belen et al. individuals’ fears and anxieties surrounding their or their loved ones’ susceptibility to the coronavirus prompt behaviors, such as social distancing, home confinement, feelings of isolation, and apprehension about the future, all of which can intensify psychological distress among teenagers [41].

In this context, Benke et al. conducted a study in Germany involving 4335 participants, among whom 75.8% were female and 24.2% were male, with an average age of 12.45 years. The results indicated a direct and indirect correlation between feelings of loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic and anxiety. Given that social interactions, particularly those with peers, significantly influence mental well-being, younger individuals were more susceptible to mental health issues and were at a heightened risk of experiencing depression and anxiety due to quarantine measures [42].

Furthermore, in European nations, numerous young individuals reside independently, thereby exacerbating the disruption to their social interactions resulting from staying at home. Research by Seyyedkalan indicated an inverse correlation between anxiety stemming from the coronavirus pandemic and students’ academic motivation; specifically, lower levels of coronavirus-induced anxiety were associated with higher levels of academic motivation among students, and conversely. In a broader perspective, among the variables scrutinized, such as social symptoms, external and intrinsic motivation, and psychological symptoms, psychological symptoms exerted the most significant influence on coronavirus-related anxiety, while external motivation played the predominant role in shaping students’ academic motivation [33].

The findings of this study align with the results of Tan, who investigated the impact of COVID-induced anxiety and online education on diminishing students’ academic motivation [43], as well as Breneiser et al., whose research [44] similarly indicates a decline in students’ motivation in online learning compared to traditional face-to-face instruction. The transition to virtual classrooms and remote learning has imposed significant challenges on educators, students, and their families [45, 46]. Moreover, research by Hiremath et al. and Omidvar et al. [47, 48] highlights that students are experiencing heightened levels of stress and anxiety, with COVID-related anxiety notably dampening their academic motivation.

One factor contributing to increased anxiety among teenagers is the lack of social support. Research suggests that lower levels of support from parents, teachers, and school administrators correlate with heightened anxiety related to the coronavirus [33]. For instance, Eyni et al.’s study underscores the relationship between perceived social support, a sense of coherence, and COVID-19-related anxiety among nurses, indicating that these factors can predict individuals’ responses to anxiety. Specifically, individuals develop a sense of coherence when they perceive that life events are manageable and resolvable, and recognize the availability of resources such as support from family, friends, and colleagues to cope with challenges. This sense of coherence empowers individuals to better navigate negative psychological states like anxiety amidst the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic [39]. These findings align with prior research by Tan (2020) [43] and Özmete and Pak (2020) [49].

Another influential factor contributing to anxiety related to the coronavirus is individuals’ level of mindfulness. Mindfulness entails directing focused and purposeful attention to the present moment, coupled with acceptance of thoughts and feelings without judgment [50]. Bigham Lal Abadi et al.’s findings suggest that individuals with higher levels of mindfulness, when exposed to COVID-19-related information, are better equipped to avoid dwelling on negative events compared to those with lower mindfulness levels. Consequently, these individuals may experience reduced rumination about the pandemic and lower levels of anxiety. Thus, adolescents who practice mindfulness and remain attuned to the present moment are less susceptible to the adverse psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, including symptoms of anxiety and feelings of loneliness [32].

In their investigation, An et al. examined mindfulness, neuroticism, and depression among Chinese adolescents following a tornado incident. The study included 455 adolescents with an average age of 14 years, of whom 208(47.0%) were male. All participants had encountered the tornado, with nine being trapped and six sustaining injuries during its occurrence. Additionally, 78 of the participants’ relatives or friends were trapped, and 80 of the participants sustained injuries as a result of their relatives or friends. A total of 27 relatives or friends of the participants lost their lives in the event. The findings suggest that individuals with elevated levels of mindfulness exhibit greater adaptability as they maintain awareness of both positive and negative occurrences in their surroundings, allowing them to respond more effectively to unfolding events in the present moment. Conversely, individuals may react involuntarily and impulsively to events rather than engage in deliberate, thoughtful responses [51].

In both investigations, the focal demographic consisted of teenagers, although the temporal context differed, with the An et al. study coinciding with a tornado incident [51]. Guo et al. conducted a study to explore the influence of social support on depression, anxiety, and stress amidst the Chinese COVID-19 pandemic. Their findings revealed a negative correlation between low social support and mental health symptoms. Specifically, women received greater social support compared to men, leading to elevated levels of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms among men [52]. Conversely, the Hafstad study, which examined symptoms of anxiety and depression among 3572 adolescents aged 13 to 16 in Norway, identified heightened levels of stress and anxiety among adolescent girls, with cultural disparities contributing to these outcomes. Additionally, the Hafstad study highlighted health disparities among adolescents in vulnerable groups during an epidemic, along with other factors influencing levels of COVID-19 anxiety, such as pre-existing mental health issues and residing in single-parent, low-income households [53].

Kazemi et al.’s findings suggest that adolescents who possess a greater degree of differentiation and an independent identity from their family are better equipped to assess situations, such as the COVID-19 epidemic, rationally and devise fundamental coping strategies [35]. Conversely, adolescents are highly attuned to psychological and social shifts due to their extensive interactions within their peer groups and the broader social sphere compared to their family members, as well as younger individuals like infants and children, thus forming intricate relationships with their peers [54]. Consequently, measures such as prolonged quarantine have engendered traumatic psychological repercussions, including confusion, anger, despair, financial distress, panic, anxiety, depression, and fear, affecting all demographic groups, particularly adolescents. Thus, post-COVID-19 efforts should prioritize fortifying familial bonds and mitigating psychological impacts by leveraging familial resources [35]. Additionally, Aref-Kashefi et al.’s findings indicate that enhancing communication skills is effective in alleviating coronavirus-related anxiety in teenagers, whereas improving self-esteem does not significantly impact such anxiety levels [30]. Given that most teenagers lack prior experience with contagious and severe illnesses during the COVID-19 era, they grapple with numerous psychological and physical challenges. Reviewed research underscores that anxiety and fear among teenagers correlate with diminished academic and social performance. Among the constraints of the present review, limited access to full-text articles hindered their inclusion in the review process. It is recommended to conduct descriptive studies on teenagers’ fears and anxieties in the post-COVID-19 era within the country to identify vulnerable individuals and implement necessary psychological interventions with careful planning.

Conclusion

During adolescence, a pivotal stage in human development, teenagers exhibit heightened psychological vulnerability, particularly toward symptoms of anxiety and fear amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Various factors, such as effective communication skills, robust social support networks, mindfulness practices, resilience, and optimistic outlooks contribute to reducing COVID-19-related anxiety levels among teenagers. Conversely, factors including insomnia, excessive news consumption, and prolonged quarantine exacerbate anxiety levels in this demographic. Thus, it is recommended that mental health professionals develop comprehensive educational programs for families and schools, recognizing the significance of addressing this issue for the enhancement of adolescent social well-being and health in the post-COVID-19 era.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and writing the original draft: Fatemeh Nematian; Analysis: Fatemeh Edalattalab; Review, editing and final approval: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors hereby thank and appreciate all the researchers whose studies were used in the present systematic review.

References

The World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a global pandemic on March 11, 2020 [1]. This declaration precipitated a myriad of psychological, physical, and social challenges worldwide [2]. As a pivotal measure to mitigate the rampant spread of the disease, governments worldwide resorted to widespread school closures [3]. Surveys conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic underscored the profound impact of school closures and home quarantine on the physical and mental well-being of adolescents [4]. During periods of school closure, adolescents exhibited reduced physical activity levels, disrupted sleep patterns, and inadequate dietary habits [4]. The pandemic and associated school closures imposed a range of adverse outcomes, including diminished physical activity, feelings of confinement, fear of contagion, social isolation from peers, academic challenges, and increased familial tension [5], Consequently, adolescents experienced heightened levels of anxiety stemming from COVID-19, leading to various maladaptive behaviors, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, anorexia nervosa, and depression [6, 7].

A study conducted by Liang et al. (2020) comprising 548 adolescent students during quarantine revealed that 40% of them exhibited mental health issues, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and psychological distress [8]. Consequently, the COVID-19 outbreak poses significant psychological stressors, potentially detrimental to students’ learning and mental well-being [9].

Furthermore, reviews of studies conducted globally have highlighted the adverse psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond its mortality, with anxiety being a predominant issue [10]. Anxiety is characterized by heightened worry and agitation concerning potential future adversities [11]. Specifically, coronavirus anxiety arises from the uncertainties surrounding the COVID-19 infection, fostering cognitive ambiguity [12]. Zhang et al.’s investigation into anxiety prevalence among students during the COVID-19 outbreak reported a prevalence rate of 31.4% [13], underscoring the vulnerability of adolescents during this period of heightened stress and anxiety [14].

The elevated stress and anxiety experienced during quarantine and social isolation, compounded by the absence of peer interaction, contribute significantly to adolescents’ psychological distress [15, 16]. Notably, research by Cerván-Lavigne et al. demonstrated that girls experienced higher levels of anxiety compared to boys amidst the COVID-19 pandemic [17]. The abrupt transition to virtual learning and the unprecedented experience of a pandemic outbreak further exacerbated fear and stress among adolescents [18, 19].

Fear, defined as the response to an imminent threat or dangerous circumstances, is a prevalent emotion during the COVID-19 pandemic [20]. Studies indicate that fear of illness and death, coupled with disruptions to daily routines, can detrimentally affect adolescents’ psychological well-being, contributing to increased anxiety and depression [21]. In a pandemic, such as the coronavirus, fear of illness and fear of death combined with the disruption of daily activities causes people to struggle with disease anxiety [22]. Pandemic viral infections can cause significant mental distress at the population level [23].

Given the pivotal role of adolescent girls in shaping future societal dynamics and the critical developmental stage of adolescence, particularly amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, identifying factors contributing to anxiety and fear in adolescent girls during both the pandemic and post-pandemic periods is imperative. The insights gleaned from this study hold promise for formulating preventive measures and interventions to mitigate mental health challenges and disorders among adolescent girls.

Methods

This is a systematic review study to explore factors associated with anxiety and fear among adolescent girls during the COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 periods in Iran. The research population comprises all scientific articles indexed in reputable databases that address this topic. The search encompassed international databases, such as PubMed, Science Direct, and Google Scholar, as well as Persian language databases, including the Scientific Information Database (SID). No time constraints were applied to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant literature. To find related articles in English language databases, we used the following keywords: “Anxiety,” “fear,” “phobia,” “adolescent,” “teenager,” “teener,” “coronavirus,” “corona,” and “COVID-19.” The keywords were used in combination via AND/OR mediators. The search strategy in the PubMed database was based on the following combination:

(Anxiety OR fear OR phobia) AND (adolescent OR teenager OR teener) AND (coronavirus OR corona OR COVID-19).

The keywords used to search in Persian databases included the combination of the words “anxiety,” “fear,” “youth,” “coronavirus,” and “COVID-19,” in multiples. Paper sources were not used because the articles published in the mentioned databases are more valid than theses that have not been written and access to internet resources is more possible than books and theses.

After searching, 19328 studies were obtained. Endnote information resource management software was used to organize the studies. At first, 18883 unrelated studies were removed by reviewing the titles of the articles. Subsequently, using the aforementioned software, and by reviewing the titles of the articles, 454 related studies were found, which were examined by the researchers by reviewing the abstracts of 40 articles. The process of entering studies into research is shown in Figure 1. The Inclusion criteria were published articles in Persian or English, conducting research in Iran, females as the target population of the article, having access to the full text of the articles, original research papers (including descriptive articles), and mentioning factors affecting anxiety. Meanwhile, review articles and letters to the editor were not selected due to a lack of primary data.

By carefully studying the title and abstract of the articles that met the inclusion criteria by the researcher, a large number of the articles were eliminated due to their weak connection with the purpose of the study. If it was not possible to decide on the article after reading the title and abstract, the authors referred to the full text. Then, to ensure the recovery of all the documents, the list of sources of articles was also searched and a qualified study was added to the analysis. Several articles were excluded due to the disproportionate age range of samples and some due to a lack of investigation of anxiety factors or relation with the COVID-19 period.

After examining the purpose of the studies and inclusion criteria, 16 studies were evaluated in terms of quality by two researchers separately. The quality of these articles was evaluated using the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) scale. This scale evaluates the articles in terms of the selection process, including representativeness of samples, sample size, location and time of the study, sampling process, description of study design, inclusion, and exclusion criteria, definition of study variables, and description of tools, and examines the results (statistical analysis, demographic characteristics, and study results). Based on the STROBE scale, the articles are scored from 0 (the weakest) to 18 (the strongest). To preserve the data, the studies that had a score lower than the average score (<9) were considered low quality.

Results

In this study, a total of 16 eligible papers were systematically reviewed. The articles underwent rigorous evaluation using the STROBE checklist, as depicted in Table 1.

The findings extracted from the reviewed articles about anxiety and fear among adolescent girls during both the COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 periods are synthesized and presented in Table 2.

Discussion

The current research discerned the factors associated with anxiety and fear among adolescent girls during the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath. The study findings revealed a notable prevalence of anxiety among teenagers amid the COVID-19 outbreak. Factors contributing to this phenomenon include the developmental stage of adolescence, paternal occupation, limited knowledge about the disease, apprehension stemming from its unknown nature, diminished parental support, prolonged periods of quarantine, restricted autonomy of teenagers, and reduced social interactions with peers.

The limited scientific knowledge surrounding the coronavirus has a significant impact on adolescent girls [40], who are more susceptible, which exacerbates their anxiety. The prevailing uncertainty and cognitive ambiguity associated with this virus contribute to widespread anxiety among teenagers. Fear of the unknown has historically been a catalyst for anxiety across human societies. Presently, the escalation of mental distress attributed to the proliferation of infectious diseases within society notably amplifies fear and anxiety levels. COVID-19 anxiety manifests as a physiological and psychological response when individuals perceive an imbalance between their capabilities and the demands imposed by the pandemic. This imbalance during the era of COVID-19 anxiety detrimentally affects adolescents’ learning outcomes [34]. According to Belen et al. individuals’ fears and anxieties surrounding their or their loved ones’ susceptibility to the coronavirus prompt behaviors, such as social distancing, home confinement, feelings of isolation, and apprehension about the future, all of which can intensify psychological distress among teenagers [41].

In this context, Benke et al. conducted a study in Germany involving 4335 participants, among whom 75.8% were female and 24.2% were male, with an average age of 12.45 years. The results indicated a direct and indirect correlation between feelings of loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic and anxiety. Given that social interactions, particularly those with peers, significantly influence mental well-being, younger individuals were more susceptible to mental health issues and were at a heightened risk of experiencing depression and anxiety due to quarantine measures [42].

Furthermore, in European nations, numerous young individuals reside independently, thereby exacerbating the disruption to their social interactions resulting from staying at home. Research by Seyyedkalan indicated an inverse correlation between anxiety stemming from the coronavirus pandemic and students’ academic motivation; specifically, lower levels of coronavirus-induced anxiety were associated with higher levels of academic motivation among students, and conversely. In a broader perspective, among the variables scrutinized, such as social symptoms, external and intrinsic motivation, and psychological symptoms, psychological symptoms exerted the most significant influence on coronavirus-related anxiety, while external motivation played the predominant role in shaping students’ academic motivation [33].

The findings of this study align with the results of Tan, who investigated the impact of COVID-induced anxiety and online education on diminishing students’ academic motivation [43], as well as Breneiser et al., whose research [44] similarly indicates a decline in students’ motivation in online learning compared to traditional face-to-face instruction. The transition to virtual classrooms and remote learning has imposed significant challenges on educators, students, and their families [45, 46]. Moreover, research by Hiremath et al. and Omidvar et al. [47, 48] highlights that students are experiencing heightened levels of stress and anxiety, with COVID-related anxiety notably dampening their academic motivation.

One factor contributing to increased anxiety among teenagers is the lack of social support. Research suggests that lower levels of support from parents, teachers, and school administrators correlate with heightened anxiety related to the coronavirus [33]. For instance, Eyni et al.’s study underscores the relationship between perceived social support, a sense of coherence, and COVID-19-related anxiety among nurses, indicating that these factors can predict individuals’ responses to anxiety. Specifically, individuals develop a sense of coherence when they perceive that life events are manageable and resolvable, and recognize the availability of resources such as support from family, friends, and colleagues to cope with challenges. This sense of coherence empowers individuals to better navigate negative psychological states like anxiety amidst the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic [39]. These findings align with prior research by Tan (2020) [43] and Özmete and Pak (2020) [49].

Another influential factor contributing to anxiety related to the coronavirus is individuals’ level of mindfulness. Mindfulness entails directing focused and purposeful attention to the present moment, coupled with acceptance of thoughts and feelings without judgment [50]. Bigham Lal Abadi et al.’s findings suggest that individuals with higher levels of mindfulness, when exposed to COVID-19-related information, are better equipped to avoid dwelling on negative events compared to those with lower mindfulness levels. Consequently, these individuals may experience reduced rumination about the pandemic and lower levels of anxiety. Thus, adolescents who practice mindfulness and remain attuned to the present moment are less susceptible to the adverse psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, including symptoms of anxiety and feelings of loneliness [32].

In their investigation, An et al. examined mindfulness, neuroticism, and depression among Chinese adolescents following a tornado incident. The study included 455 adolescents with an average age of 14 years, of whom 208(47.0%) were male. All participants had encountered the tornado, with nine being trapped and six sustaining injuries during its occurrence. Additionally, 78 of the participants’ relatives or friends were trapped, and 80 of the participants sustained injuries as a result of their relatives or friends. A total of 27 relatives or friends of the participants lost their lives in the event. The findings suggest that individuals with elevated levels of mindfulness exhibit greater adaptability as they maintain awareness of both positive and negative occurrences in their surroundings, allowing them to respond more effectively to unfolding events in the present moment. Conversely, individuals may react involuntarily and impulsively to events rather than engage in deliberate, thoughtful responses [51].

In both investigations, the focal demographic consisted of teenagers, although the temporal context differed, with the An et al. study coinciding with a tornado incident [51]. Guo et al. conducted a study to explore the influence of social support on depression, anxiety, and stress amidst the Chinese COVID-19 pandemic. Their findings revealed a negative correlation between low social support and mental health symptoms. Specifically, women received greater social support compared to men, leading to elevated levels of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms among men [52]. Conversely, the Hafstad study, which examined symptoms of anxiety and depression among 3572 adolescents aged 13 to 16 in Norway, identified heightened levels of stress and anxiety among adolescent girls, with cultural disparities contributing to these outcomes. Additionally, the Hafstad study highlighted health disparities among adolescents in vulnerable groups during an epidemic, along with other factors influencing levels of COVID-19 anxiety, such as pre-existing mental health issues and residing in single-parent, low-income households [53].

Kazemi et al.’s findings suggest that adolescents who possess a greater degree of differentiation and an independent identity from their family are better equipped to assess situations, such as the COVID-19 epidemic, rationally and devise fundamental coping strategies [35]. Conversely, adolescents are highly attuned to psychological and social shifts due to their extensive interactions within their peer groups and the broader social sphere compared to their family members, as well as younger individuals like infants and children, thus forming intricate relationships with their peers [54]. Consequently, measures such as prolonged quarantine have engendered traumatic psychological repercussions, including confusion, anger, despair, financial distress, panic, anxiety, depression, and fear, affecting all demographic groups, particularly adolescents. Thus, post-COVID-19 efforts should prioritize fortifying familial bonds and mitigating psychological impacts by leveraging familial resources [35]. Additionally, Aref-Kashefi et al.’s findings indicate that enhancing communication skills is effective in alleviating coronavirus-related anxiety in teenagers, whereas improving self-esteem does not significantly impact such anxiety levels [30]. Given that most teenagers lack prior experience with contagious and severe illnesses during the COVID-19 era, they grapple with numerous psychological and physical challenges. Reviewed research underscores that anxiety and fear among teenagers correlate with diminished academic and social performance. Among the constraints of the present review, limited access to full-text articles hindered their inclusion in the review process. It is recommended to conduct descriptive studies on teenagers’ fears and anxieties in the post-COVID-19 era within the country to identify vulnerable individuals and implement necessary psychological interventions with careful planning.

Conclusion

During adolescence, a pivotal stage in human development, teenagers exhibit heightened psychological vulnerability, particularly toward symptoms of anxiety and fear amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Various factors, such as effective communication skills, robust social support networks, mindfulness practices, resilience, and optimistic outlooks contribute to reducing COVID-19-related anxiety levels among teenagers. Conversely, factors including insomnia, excessive news consumption, and prolonged quarantine exacerbate anxiety levels in this demographic. Thus, it is recommended that mental health professionals develop comprehensive educational programs for families and schools, recognizing the significance of addressing this issue for the enhancement of adolescent social well-being and health in the post-COVID-19 era.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and writing the original draft: Fatemeh Nematian; Analysis: Fatemeh Edalattalab; Review, editing and final approval: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors hereby thank and appreciate all the researchers whose studies were used in the present systematic review.

References

- Fawaz M, Samaha A. COVID-19 quarantine: Post-traumatic stress symptomatology among Lebanese citizens. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020; 66(7):666-74. [DOI:10.1177/0020764020932207] [PMID]

- Weerahandi H, Hochman KA, Simon E, Blaum C, Chodosh J, Duan E, et al. Post-discharge health status and symptoms in patients with severe COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2021; 36:738-45. [DOI:10.1007/s11606-020-06338-4] [PMID]

- UNESCO. COVID-19 educational disruption and response. Paris: UNESCO; 2020. [Link]

- Mason F, Farley A, Pallan M, Sitch A, Easter C, Daley AJ. Effectiveness of a brief behavioural intervention to prevent weight gain over the Christmas holiday period: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2018; 363:k4867. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.k4867] [PMID]

- Nematian F, Tagharrobi Z, Sooki Z, Sharifi Kh. The effects of positive thinking education for adolescent girls on their conflicts with their mothers: A randomized controlled trial. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2022; 11(3):190-7. [DOI:10.4103/nms.nms_16_22]

- Wang G, Zhang Y, Zhao J, Zhang J, Jiang F. Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet. 2020; 395(10228):945-7. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X] [PMID]

- Power E, Hughes S, Cotter D, Cannon M. Youth mental health in the time of COVID-19. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020; 37(4):301-5. [DOI:10.1017/ipm.2020.84] [PMID]

- Liang L, Ren H, Cao R, Hu Y, Qin Z, Li C, et al. The effect of COVID-19 on youth mental health. Psychiatr Q. 2020; 91(3):841-52. [DOI:10.1007/s11126-020-09744-3] [PMID]

- Al-Rabiaah A, Temsah MH, Al-Eyadhy AA, Hasan GM, Al-Zamil F, Al-Subaie S, et al. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-Corona Virus (MERS-CoV) associated stress among medical students at a university teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2020; 13(5):687-91. [DOI:10.1016/j.jiph.2020.01.005] [PMID]

- Fardin MA. COVID-19 and anxiety: A review of psychological impacts of infectious disease outbreaks. Arch Clin Infect Dis. 2020; 15(COVID-19):e102779. [DOI:10.5812/archcid.102779]

- Hancock KM, Swain J, Hainsworth CJ, Dixon AL, Koo S, Munro K. Acceptance and commitment therapy versus cognitive behavior therapy for children with anxiety: Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018; 47(2):296-311. [DOI:10.1080/15374416.2015.1110822] [PMID]

- Alipour A, Ghadami A, Alipour Z, Abdollahzadeh H. Preliminary validation of the Corona Disease Anxiety Scale (CDAS) in the Iranian sample. J Health Psychol. 2020; 8(32):163-75. [DOI:10.30473/hpj.2020.52023.4756]

- Zhang Z, Zhai A, Yang M, Zhang J, Zhou H, Yang C. Prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms of high school students in shandong province during the COVID-19 epidemic. Front Psychiatry. 2020; 11:570096. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.570096] [PMID]

- Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Erhart M, Devine J, Schlack R, Otto C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022; 31(6):879-89. [DOI:10.1007/s00787-021-01726-5] [PMID]

- Francisco R, Pedro M, Delvecchio E, Espada JP, Morales A, Mazzeschi C, et al. Psychological symptoms and behavioral changes in children and adolescents during the early phase of COVID-19 quarantine in three European countries. Front Psychiatry. 2020; 11:570164. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.570164] [PMID]

- Waite P, Pearcey S, Shum A, Raw JAL, Patalay P, Creswell C. How did the mental health symptoms of children and adolescents change over early lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK? JCPP Adv. 2021; 1(1):e12009. [DOI:10.1111/jcv2.12009] [PMID]

- Lavigne-Cerván R, Costa-López B, Juárez-Ruiz de Mier R, Real-Fernández M, Sánchez-Muñoz de León M, Navarro-Soria I. Consequences of COVID-19 confinement on anxiety, sleep and executive functions of children and adolescents in Spain. Front Psychol. 2021; 12:565516. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.565516] [PMID]

- Wang L, Zhang Y, Chen L, Wang J, Jia F, Li F, et al. Psychosocial and behavioral problems of children and adolescents in the early stage of reopening schools after the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional study in China. Transl Psychiatry. 2021; 11(1):342. [DOI:10.1038/s41398-021-01462-z] [PMID]

- Pizarro-Ruiz JP, Ordóñez-Camblor N. Effects of COVID-19 confinement on the mental health of children and adolescents in Spain. Sci Rep. 2021; 11(1):11713. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-021-91299-9] [PMID]

- Alaki S, Alotaibi A, Almabadi E, Alanquri E. Dental anxiety in middle school children and their caregivers: Prevalence and severity. J Dent Oral Hygiene. 2012; 4(1):6-11. [DOI:10.5897/JDOH11.019]

- Vistisen HT, Sønderskov KM, Dinesen PT, Østergaard SD. Psychological well-being and symptoms of depression and anxiety across age groups during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2021; 33(6):331-4. [DOI:10.1017/neu.2021.21] [PMID]

- Alizadeh Fard S, Saffarinia M. The prediction of mental health based on the anxiety and the social cohesion that caused by Coronavirus. Soc Psychol Res. 2020; 9(36):129-41. [Link]

- Heydari S, Matins-Lorca M. [Validity and validity of the COVID-19 virus fear scale (Persian)]. Paper presented at: National Conference on Social Health in Crisis, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences and Health Services, 2 December 2020; Ahvaz, Iran.- [Link]

- Fazeli S, Mohammadi Zeidi I, Lin CY, Namdar P, Griffiths MD, Ahorsu DK, et al. Depression, anxiety, and stress mediate the associations between internet gaming disorder, insomnia, and quality of life during the COVID-19 outbreak. Addict Behav Rep. 2020; 12:100307. [DOI:10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100307] [PMID]

- Sheikhi S, Beikzadeh Oskoei A, Ghayourvahdat B, Nasirian AH. Prediction of psychological distress based on coronavirus anxiety and self-care among Iranian adolescents during the coronavirus epidemic. Chron Dis J. 2022; 10(1):13-19. [DOI:10.22122/cdj.v10i1.682]

- Ghorbani S, Afshari M, Eckelt M, Dana A, Bund A. Associations between physical activity and mental health in Iranian adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: An accelerometer-based study. Children (Basel). 2021; 8(11):1022. [DOI:10.3390/children8111022] [PMID]

- Khosrojerdi Z, Pakdaman S. [Adolescents Corona anxiety: The relationship between character strengths and family social support (Persian)]. Iran J Health Psychol. 2022; 5(1):49-56. [DOI:10.30473/ijohp.2022.57184.1162]

- Yazdani N, Pourarian S, Moravej H. Symptoms of stress amongst children and adolescents during the COVID-19 outbreak in Shiraz, Iran: A cross-sectional study. Iran J Pediatr. 2022; 32(3):e115173. [DOI:10.5812/ijp-115173]

- Bahrami-Samani S, Firouzbakht M, Azizi A, Omidvar S. Anxiety, depression, and predictors amongst Iranian students aged 8 to 18 years during the COVID-19 outbreak first peak. Iran J Psychiatry. 2022; 17(2):187-95. [DOI:10.18502/ijps.v17i2.8909] [PMID]

- Aref-Kashefi MS, Karimi M, Naghsh Z. The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between communication skills and anxiety in adolescents during Coronavirus pandemic. J Ment Health: Res Pract. 2022; 1(1):48-59. [DOI:10.22034/mhrp.2022.154065]

- Tofangchiha M, Lin CY, Scheerman JFM, Broström A, Ahonen H, Griffiths MD, et al. Associations between fear of COVID-19, dental anxiety, and psychological distress among Iranian adolescents. BDJ Open. 2022; 8(1):19. [DOI:10.1038/s41405-022-00112-w] [PMID]

- Bigham Lal Abadi E, Basharpoor S, Hajimoradi R. [The mediating role of mindfulness in the relationship between loneliness and COVID-19 anxiety in adolescents during the COVID-19 epidemic (Persian)]. Clinic Psychol Pers. 2022; 20(1):89-102. [DOI:10.22070/cpap.2022.15570.1186]

- Seyyedkalan S, Faryadi S, Zarei N. [The relationship between coronavirus anxiety and social support and its effects on academic motivation (Case study: Sanandaj Magnet school) (Persian)]. Pouyesh Humanit Educ. 2022; 8(27):91-106. [Link]

- Torbatinezgad H, Barani Z. [Investigating the relationship between Corona anxiety and academic isolation and cognitive skills of first secondary students in Sarakhs city (Persian)]. J Pouyesh in Educ Consult. 2023; 1401(17):1-12. [Link]

- Kazemi M, Sadeghi AR. [The relationship between self-differentiation and anxiety of COVID-19 disease in adolescents mediated by parent-child conflict (Persian)]. J Appl Fam Ther. 2020; 1(2):48-67. [DOI:10.22034/aftj.2020.113925]

- Hekmatiyan Fard S, Hoseini FS. Evaluation of coronary anxiety in adolescents of families with disease’s COVID-19: The moderating role of social support and resilience in relation to mental well-being. J Mod Psychol Res. 2022; 17(66):109-19. [Link]

- Shomaliahmadabadi M, Barkhordariahmadabadi A, Poorjanebolahi M. [The role of COVID-19 anxiety, worry and negative metacognitive beliefs in predicting learning anxiety of student in the COVID-19 epidemic (Persian)]. New Approach Educ Sci. 2021; 3(4):1-10. [DOI:10.22034/naes.2021.277883.1107]

- Asanjarani F, Arslan G, Alqashan HF, Sadeghi P. Coronavirus stress and adolescents’ internalizing problems: Exploring the effect of optimism and pessimism. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2022; 17(3):281-8. [DOI:10.1080/17450128.2021.2020386]

- Eyni S, Ziyar M, Ebadi MJ. Mental health of students during the Corona epidemic: The role of predictors of Corona anxiety, cognitive distortion, and psychological hardiness. Rooyesh. 2021;10(7):25-34. [Link]

- Sobhani S, Falahzade H, Pourshahriar H. Predicting the tendency to self-harming behaviors in teenage girls 13 to 15 years old based on psychological capital and family performance. J Fam Res. 2023; 18(4):755-75. [DOI:10.52547/JFR.18.4.755]

- Belen H. Fear of COVID-19 and mental health: The role of mindfulness in during times of crisis. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2022; 20(1):607-18. [DOI:10.1007/s11469-020-00470-2] [PMID]

- Benke C, Autenrieth LK, Asselmann E, Pané-Farré CA. Stay-at-home orders due to the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with elevated depression and anxiety in younger, but not older adults: Results from a nationwide community sample of adults from Germany. Psychol Med. 2022; 52(15):3739-40. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291720003438] [PMID]

- Tan C. The impact of COVID-19 on student motivation, community of inquiry and learning performance. Asian Educ Dev Stud. 2020; 10(2):308-21. [DOI:10.1108/AEDS-05-2020-0084]

- Breneiser JE, Rodefer JS, Tost JR. Using tutorial videos to enhance the learning of statistics in an online undergraduate psychology course. North Am J Psychol. 2018; 20(3):715. [Link]

- Cachón-Zagalaz J, Sánchez-Zafra M, Sanabrias-Moreno D, González-Valero G, Lara-Sánchez AJ, Zagalaz-Sánchez ML. Systematic review of the literature about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lives of school children. Front Psychol. 2020; 11:569348. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.569348] [PMID]

- Hiraoka D, Tomoda A. Relationship between parenting stress and school closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020; 74(9):497-98. [DOI:10.1111/pcn.13088] [PMID]

- Hiremath P, Kowshik CS, Manjunath M, Shettar M. COVID 19: Impact of lock-down on mental health and tips to overcome. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020; 51:102088. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102088] [PMID]

- Omidvar H, Omidvar K, Omidvar A. [The determination of effectiveness of teaching time management strategies on the mental health and academic motivation of school students (Persian)]. J School Psychol. 2013; 2(3):6-22. [DOI:d-2-3-92-7-1]

- Özmete E, Pak M. The relationship between anxiety levels and perceived social support during the pandemic of COVID-19 in Turkey. Soc Work Public Health. 2020; 35(7):603-16. [DOI:10.1080/19371918.2020.1808144] [PMID]

- Kabat-Zinn J, Hanh TN. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York: Random House Publishing Group; 2009. [Link]

- An Y, Fu G, Yuan G, Zhang Q, Xu W. Dispositional mindfulness mediates the relations between neuroticism and posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in Chinese adolescents after a tornado. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019; 24(3):482-93. [DOI:10.1177/1359104518822672] [PMID]

- Guo K, Zhang X, Bai S, Minhat HS, Nazan AINM, Feng J, et al. Assessing social support impact on depression, anxiety, and stress among undergraduate students in Shaanxi province during the COVID-19 pandemic of China. PLoS One. 2021; 16(7):e0253891. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0253891] [PMID]

- Hafstad GS, Sætren SS, Wentzel-Larsen T, Augusti EM. Adolescents' symptoms of anxiety and depression before and during the Covid-19 outbreak - a prospective population-based study of teenagers in Norway. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021; 5:100093. [DOI: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100093] [PMID]

- Orben A, Tomova L, Blakemore SJ. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020; 4(8):634-40. [DOI:10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30186-3] [PMID]

Type of Study: Review Article |

Subject:

Psychiatry Nursing

Received: 2023/11/12 | Accepted: 2023/12/29 | Published: 2024/01/1

Received: 2023/11/12 | Accepted: 2023/12/29 | Published: 2024/01/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |