Volume 13, Issue 4 (10-2025)

J. Pediatr. Rev 2025, 13(4): 289-302 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Taksande A, Taksande A, Malik A. Pediatric Strokes: Types, Risk Factors, Symptoms, Treatments, and Diagnosis. J. Pediatr. Rev 2025; 13 (4) :289-302

URL: http://jpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-626-en.html

URL: http://jpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-626-en.html

1- Department of Paediatrics, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research, Wardha, India. , amar.taksande@gmail.com

2- Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research, Wardha, India.

3- Department of Paediatrics, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research, Wardha, India.

2- Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research, Wardha, India.

3- Department of Paediatrics, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research, Wardha, India.

Full-Text [PDF 1389 kb]

(607 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (934 Views)

Circulatory considerations in pediatric stroke

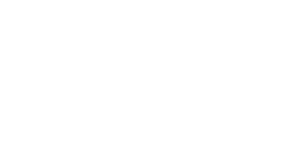

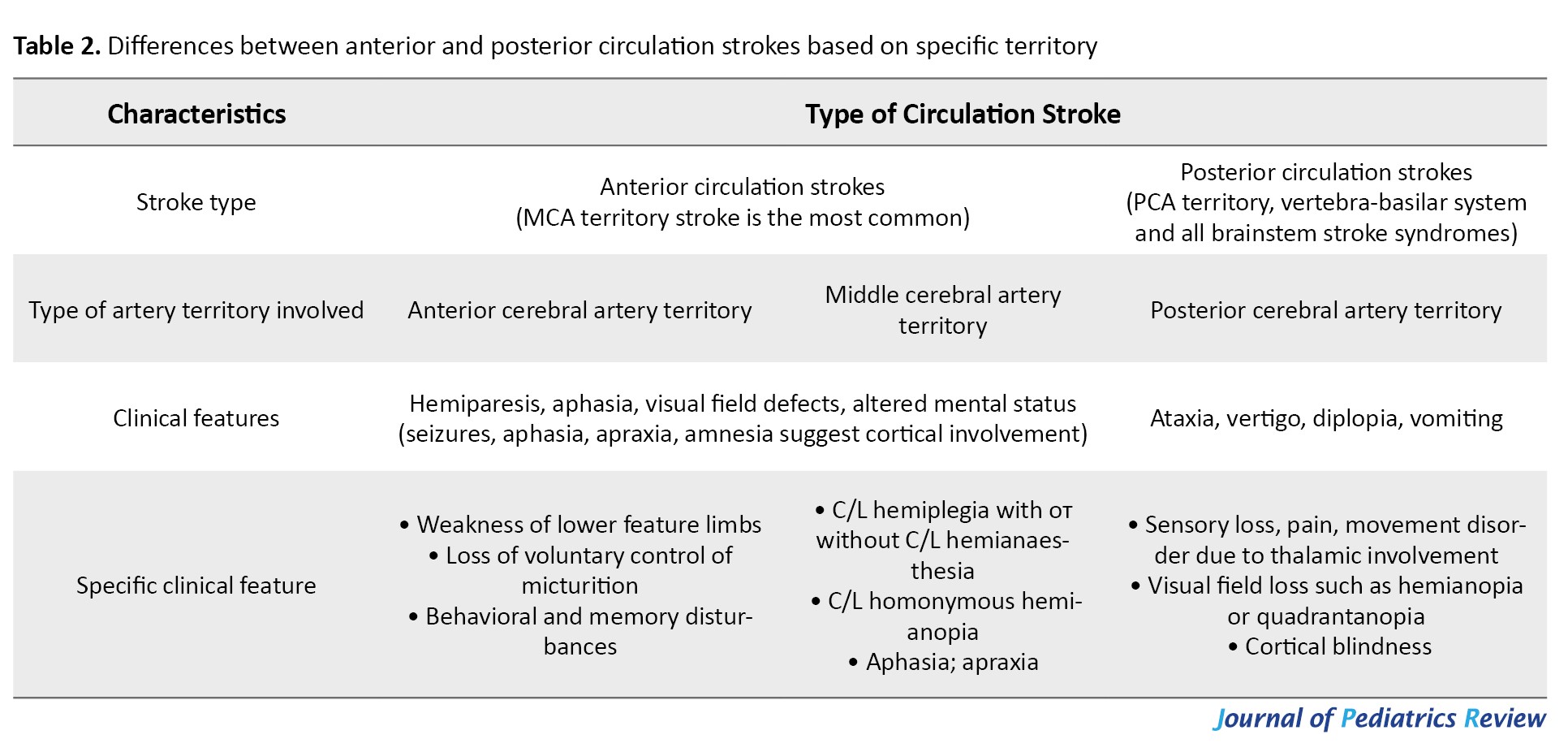

The brain receives its blood supply from two major systems: The anterior circulation through the internal carotid arteries, and the posterior circulation via the vertebrobasilar system, both of which meet at the circle of Willis. In children, strokes are more often seen in MCA territory than in the ACA or PCA territories. When the anterior circulation is affected, symptoms depend on which side of the brain is involved. For example, right-sided strokes in right-handed children often cause language difficulties (aphasia), while left-sided strokes more commonly lead to problems with visuospatial perception. Strokes in the posterior circulation tend to cause visual field defects, trouble recognizing colors or objects, double vision (diplopia), dizziness or vertigo, crossed motor signs (meaning brainstem involvement), and balance problems [6, 14]. The differences between anterior and posterior circulation strokes are summarized in Table 2.

Methods of pediatric stroke diagnosis

In the acute setting, brain imaging is a cornerstone of stroke diagnosis in children. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) are the primary tools, with vascular imaging through CT angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) providing essential details about blood vessel involvement. In some cases, advanced techniques like perfusion imaging can be used to assess brain tissue viability. Children at high risk for stroke should undergo immediate neurological assessment followed by urgent imaging. While MRI is the preferred modality, a CT scan—ideally combined with CTA—should be completed within one hour of arrival if MRI is not available [34, 35]. For CVST, when MRI is unavailable, contrast-enhanced CT scans can help, showing classic signs such as the “empty-delta” on contrast CT or the dense triangle sign on plain CT. For HS diagnosis, CT scans are typically the first choice because they are very sensitive in detecting acute bleeding. A thorough evaluation usually involves a CT brain scan combined with CTA, as well as MRI with susceptibility-weighted imaging to detect even small amounts of bleeding. In specialized centers, digital subtraction angiography (DSA) might be performed for a more detailed view. Advanced MRI techniques are very effective at identifying residual blood products after most brain bleeds. Angiographic studies, whether done by CT, MRI, or conventional methods, are important to rule out vascular abnormalities like AV malformations or aneurysms.

CT brain imaging

A CT scan is often the first-line investigation, particularly when an HS is suspected. However, their ability to detect early ischemic changes is limited, especially in the first 12 hours after symptom onset. In fact, over half of children with AIS may have a normal initial CT. That said, CT remains useful in certain settings (e.g. when MRI is unavailable) or for detecting calcifications, such as those seen in mineralizing angiopathy of the lenticulostriate arteries. CTA is often limited to the brain in hemorrhagic cases but can extend to the neck in ischemic events without bleeding. Although CT can reliably detect large infarcts and exclude hemorrhage, MRI is much better at identifying small or early infarcts [36, 37].

MRI brain imaging

MRI, especially when combined with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI), is regarded as the gold standard for diagnosing AIS in children. DWI is particularly valuable because it detects cytotoxic edema early, allowing stroke to be identified even when standard MRI or CT scans appear normal. MRA is also useful in visualizing vascular occlusions, arteriopathies, and abnormalities in blood flow. MRI is highly sensitive in detecting small infarcts, lesions in the posterior fossa, hemorrhagic transformations, multiple infarcts, and flow voids that suggest vessel narrowing or blockage. In cases of AIS, MRA should ideally include imaging from the aortic arch to the vertex of the brain, while in HS cases, imaging may focus on the intracranial vessels. However, since many pediatric patients require sedation or anesthesia for MRI, practical considerations related to safety and logistics are important. If MRI is not possible, CTA serves as a dependable alternative.

Advanced imaging and acute interventions

When AIS is confirmed within 4 hours and HS is ruled out, clinicians may consider thrombolytic therapy with IV tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or mechanical thrombectomy, although these are used with caution due to limited pediatric data. For CVST, a combination of MRI and MR venography is the preferred diagnostic approach.

DSA

DSA remains the most detailed imaging technique for assessing vascular flow, inflammation, aneurysms, and emboli. It is especially valuable in diagnosing moyamoya disease, where it reveals the classic “puff of smoke” appearance. DSA is typically reserved for cases where the cause of stroke is unclear after initial imaging [6].

Additional diagnostic methods

In addition to imaging, a thorough diagnostic evaluation should be done to identify underlying risk factors:

Electroencephalography (EEG): Helps distinguish between seizures, migraines, or other causes of transient neurological symptoms.

Echocardiography: Recommended for all pediatric stroke patients to identify potential cardiac sources of emboli, such as patent foramen ovale (PFO) or ventricular dysfunction.

Hemoglobin electrophoresis: Essential for diagnosing hemoglobinopathies like SCD.

Thrombophilia panel: Evaluation should include screening for both inherited and acquired prothrombotic conditions. This involves testing for deficiencies in protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III, as well as identifying genetic mutations such as factor V Leiden and the prothrombin G20210A mutation. Additionally, the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies should be assessed, along with measuring levels of lipoprotein (a) and homocysteine, as elevations in these markers can increase the risk of thrombotic events.

Infectious and metabolic screening: Important for identifying infections such as VZV, endocarditis, or syphilis that may trigger vascular inflammation or thrombosis.

Immunologic testing: May be necessary in children with suspected autoimmune or immunodeficiency disorders.

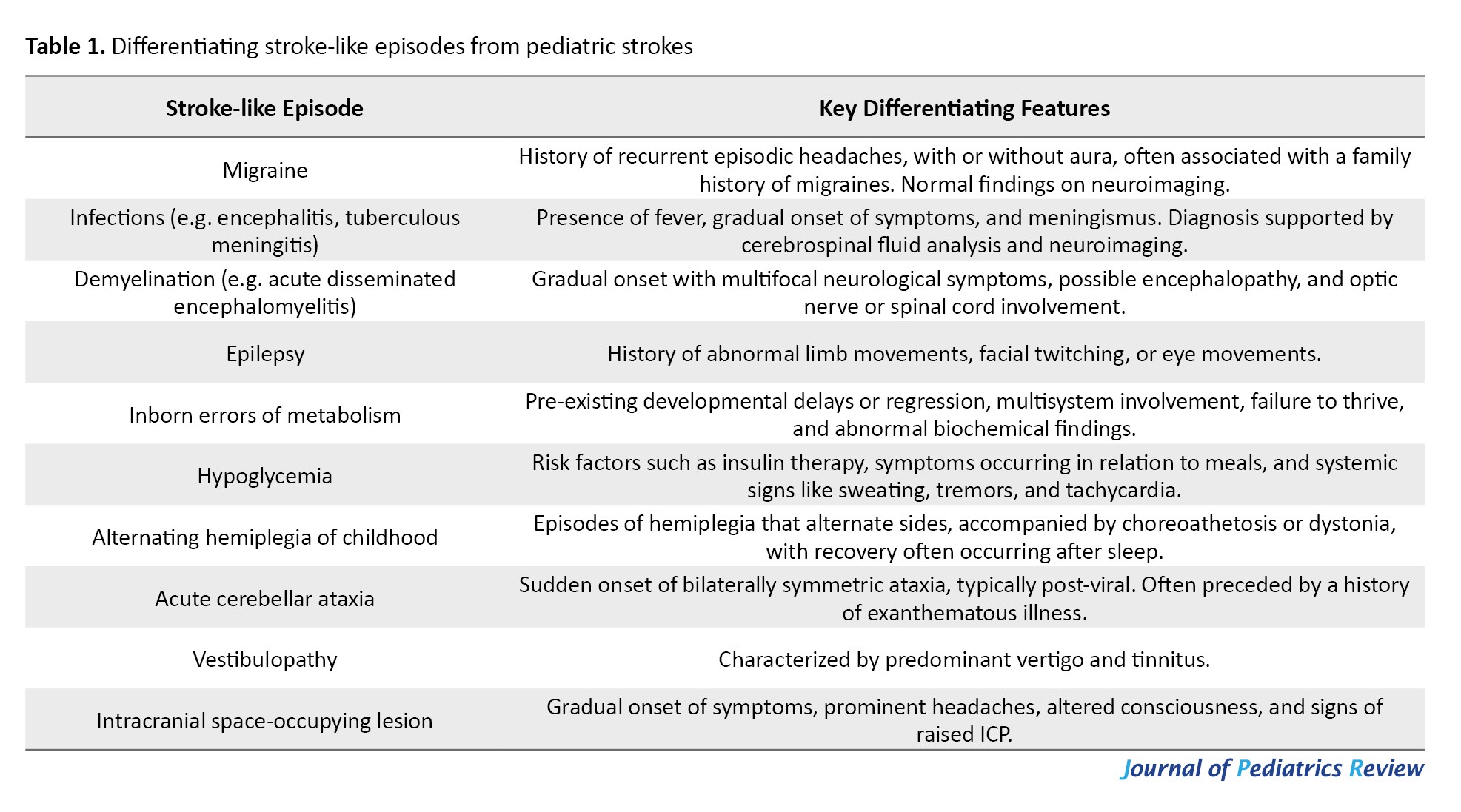

Optional investigations: In more complex cases, additional investigations are often necessary to distinguish stroke from other conditions that may present with similar symptoms, as presented in Table 1. A thorough diagnostic workup helps ensure accurate identification and appropriate management of the underlying condition [14, 38, 39].

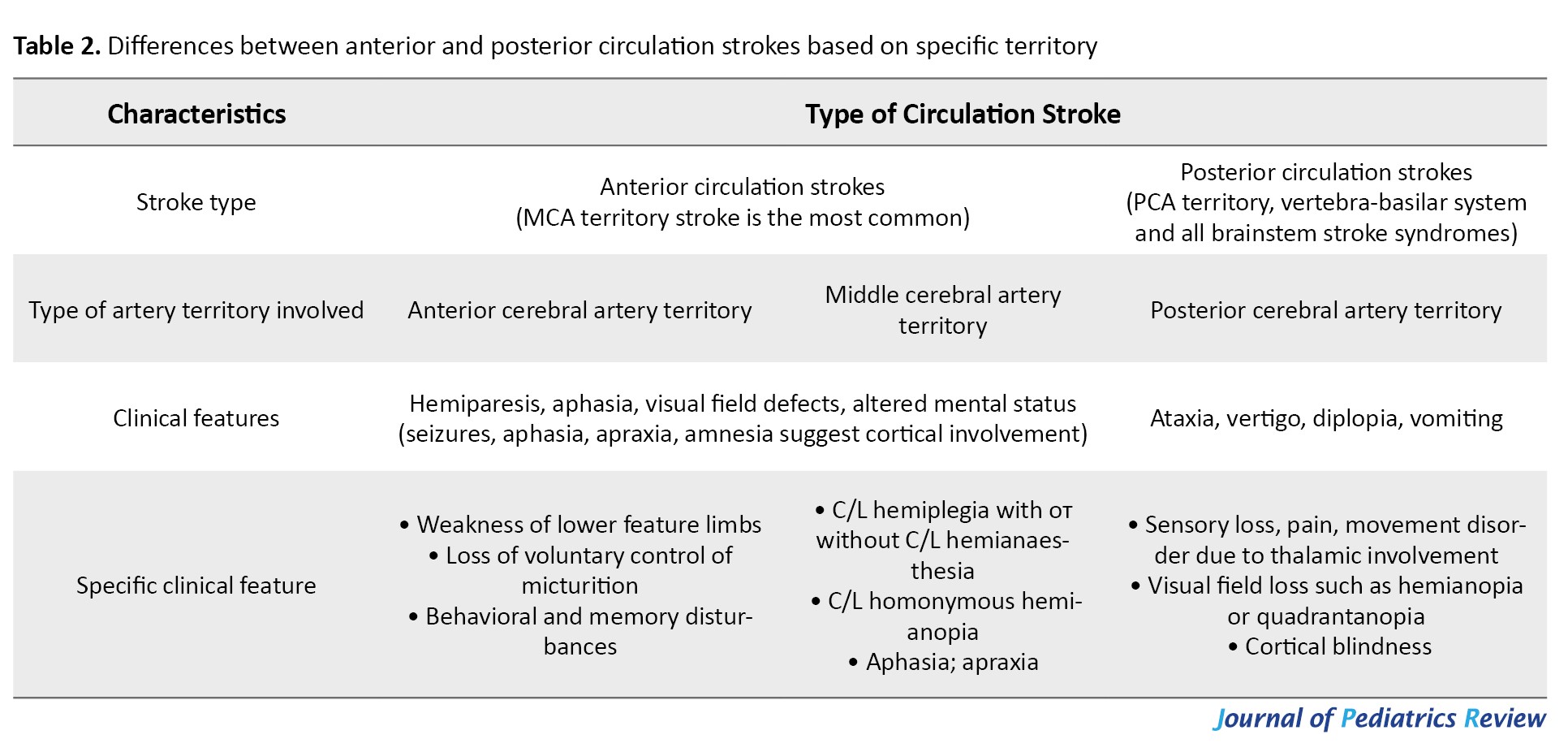

Pediatric stroke management methods

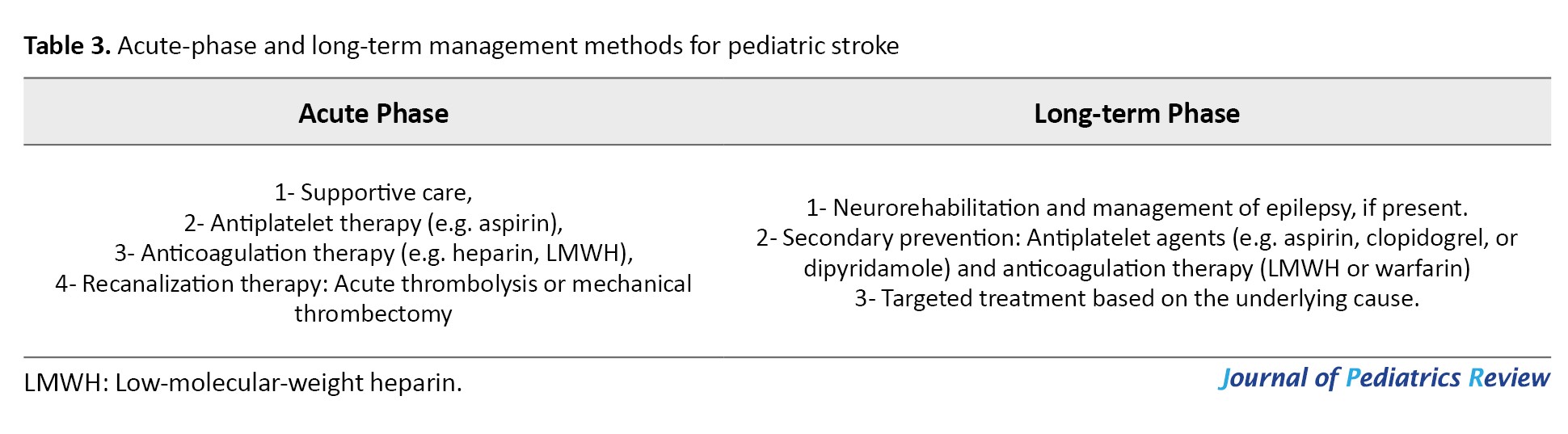

While pediatric stroke management often draws from adult stroke treatment protocols, it is important to recognize that key differences exist, especially when it comes to acute interventions like anticoagulation, thrombolysis, and mechanical thrombectomy. Due to limited data in children, these treatments require careful consideration and are not routinely recommended. Management should be comprehensive, addressing both acute-phase stabilization and long-term rehabilitation and secondary prevention. A structured approach that balances immediate care with ongoing support is essential for optimizing outcomes in affected children (Table 3).

Acute-phase management methods

Supportive care: Effective management of pediatric stroke begins with stabilizing the basics—ensuring the child’s airway is clear, breathing is adequate, and circulation is stable. To prevent complications such as aspiration, oral intake should be withheld until the swallowing ability is carefully assessed. Maintaining normal body temperature and oxygen levels is critical, and blood sugar should be kept within a safe range, avoiding both low and high extremes. While a modest rise in blood pressure is often tolerated, any low blood pressure must be corrected promptly using intravenous fluids, keeping the head flat when necessary, and employing vasopressors if required.

When cerebral edema occurs due to large ischemic strokes, it can cause dangerous increases in ICP. It is vital to regularly monitor children for signs such as headaches that worsen with position changes, vomiting, irritability or agitation, changes in consciousness, sixth cranial nerve palsy, and swelling of the optic nerve (papilledema). The development of Cushing’s triad—high blood pressure, slow heart rate, and abnormal breathing—signals severe ICP elevation but typically appears in later stages. Managing cerebral edema involves promptly correcting factors such as low oxygen (hypoxia), high carbon dioxide (hypercarbia), and low blood pressure, elevating the head of the bed to about 30 degrees, and ensuring proper head and neck positioning to support venous drainage. For intubated patients, muscle relaxants can control shivering, and pain relief is important to prevent spikes in ICP caused by discomfort. Medical treatments may include carefully controlled hyperventilation to lower carbon dioxide levels, along with hyperosmolar therapies such as intravenous mannitol or hypertonic saline to draw fluid out of the brain. Continuous monitoring of blood osmolarity and electrolytes is essential to avoid complications such as dehydration, low blood pressure, or kidney issues. If these measures fail and ICP remains dangerously high or if there is significant brain swelling causing pressure effects, surgical options like decompressive craniectomy may be necessary [13-41].

Respiratory status and oxygen saturation should be closely observed, and supplemental oxygen should be provided only if levels fall below 95%, since routine oxygen therapy has not been shown to benefit children without hypoxemia. Seizures frequently accompany AISs in children. Unless the child has active seizures or a history of epilepsy, preventative seizure medications are generally not recommended. However, if seizures occur, starting antiseizure drugs—such as levetiracetam—is a reasonable approach during the acute phase. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to support therapeutic hypothermia for pediatric stroke outside of clinical trials. Therefore, cooling strategies should be avoided until more data confirms safety and effectiveness. Once the child is stabilized, early planning for rehabilitation is crucial. Starting physiotherapy and mobilization as soon as possible helps reduce complications such as aspiration pneumonia, bedsores, blood clots, and joint contractures.

Antiplatelet therapy: For most children diagnosed with AIS, starting antiplatelet treatment—usually aspirin at a dose of 3-5 mg per kg per day (up to a maximum of 325 mg daily) within the first 24 hours is generally advised, unless there are contraindications such as bleeding into the brain (hemorrhagic transformation) [13]. It is important to avoid aspirin and other blood-thinning medications during the first day after intravenous thrombolysis, as these can increase bleeding risks. There’s growing evidence that clopidogrel might be a good alternative to aspirin in children, showing similar effectiveness. However, aspirin should never be given during viral illnesses, such as influenza or chickenpox, due to the risk of Reye syndrome, a rare but serious condition.

Anticoagulant therapy: For children with AIS who are considered high-risk, like those with cardioembolic stroke, arterial dissection, or clotting disorders, anticoagulant treatment using heparin or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is typically recommended. LMWH is usually started as soon as the diagnosis is made and continued until these specific risk factors are excluded. A common dosing for enoxaparin, a type of LMWH, is 1 mg/kg given by subcutaneous injection every 12 hours [13].

Recanalization therapy: Recanalization treatments, such as acute thrombolytic therapy or mechanical thrombectomy, might be considered for certain carefully chosen children under 18 who experience AIS. However, there is still limited information available on the safety and effectiveness of these procedures in pediatric patients [13-41]. Case reports have shown positive results in children who meet the same criteria as adults for intravenous thrombolysis. When tPA is given within 4.5 hours after symptom onset, the risk of serious brain bleeding is low [42]. Since pediatric stroke is rare and conducting large trials is difficult, alteplase (a type of tPA) may be considered for adolescents ≥13 years who meet adult treatment guidelines [40]. Although tenecteplase is gaining popularity for adult stroke care, its safety and proper dosing in children have not been well established yet [43]. Therefore, outside of clinical studies, the use of tPA in children with AIS is generally not recommended.

For CVST, the use of tPA has a stronger backing (class II recommendation), as there is better evidence supporting thrombolytic treatment in intravenous strokes among children. A review study suggested that intravenous thrombolysis might be an option for kids aged 1 month to 18 years who meet adult criteria, especially in severe cases involving major artery blockages, significant blood clotting disorders, or basilar artery occlusion with concerning clinical and imaging findings [42].

Mechanical thrombectomy can be considered for children with AIS caused by blockages in large vessels, including the end of the internal carotid artery, the beginning segment of the MCA (M1), or the basilar artery. Although this treatment is backed by level C evidence and carries a class iIb recommendation, its use in pediatric stroke is still debated. While recanalization therapies like thrombectomy are well-established in adult stroke care, their effectiveness and safety in children require further study [13, 40, 41].

Long-term management methods

Neurorehabilitation: Children who survive a stroke require a carefully planned neurorehabilitation program that targets the various challenges they may face, including physical, cognitive, language, behavioral, and adaptive difficulties. Without proper neurorehabilitation, more than half of these children are likely to have lasting neurological problems. Early and consistent use of therapies such as physiotherapy, along with medications to reduce muscle spasticity, plays a crucial role in improving motor function and helping these children regain as much independence as possible after an ischemic stroke [13, 44].

Secondary prevention: The risk of stroke or TIA recurring in children ranges from 7% to 35%, making long-term prevention methods such as antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies a critical focus in ongoing care. In antiplatelet therapy, aspirin is commonly prescribed at a dose of 1-5 mg/kg/day for most cases of ischemic stroke, except when the stroke is caused by cardioembolism, arterial dissection, or an underlying hypercoagulable condition. This treatment is generally maintained for about two years, as this period carries the highest chance of recurrence. In anticoagulant therapy, warfarin is used as one of the most effective options for long-term anticoagulation in children and plays an important role in secondary stroke prevention. Since warfarin takes several days to become fully effective, LMWH is often given initially as a bridge therapy. The typical target international normalized ratio (INR) is between 2 and 3, but for children with mechanical heart valves, a slightly higher INR range of 2.5 to 3.5 is recommended. Warfarin is especially indicated in cases of cardioembolic stroke linked to congenital or acquired heart disease, hypercoagulable disorders, and arterial dissection [13, 45].

Targeted treatments based on underlying causes

Treatment for pediatric AIS is carefully tailored to address the specific cause behind the stroke. For children whose stroke is linked to arteriopathy (except those with adenosine deaminase 2 deficiency), aspirin is preferred over anticoagulants, typically given at 3-5 mg/kg per day, up to a maximum of 81 mg daily. This antithrombotic therapy is usually continued for about two years, as this timeframe carries the highest risk for stroke recurrence. In cases of primary CNS vasculitis, steroids and immunosuppressive treatments may be used to control inflammation.

When stroke results from arterial dissection, treatment generally involves aspirin at 3-5 mg/kg daily or anticoagulation using warfarin or LMWH for 3-6 months. After this initial period, patients usually transition to long-term aspirin therapy. Children and young adults with symptomatic moyamoya disease are often recommended to undergo revascularization surgery. Common surgical options include EDAMS (Encephalo-duro-arterio-myo-synangiosis) or EDASS (Encephalo-duro-arteriosynangiosis), which aim to restore adequate blood flow to the brain.

If a cardioembolic source is suspected, especially in children with complex congenital heart defects, short-term anticoagulation with either LMWH or unfractionated heparin (UFH) is initiated, while vascular imaging and echocardiography are performed to confirm the diagnosis. If no cardioembolic cause is identified, anticoagulation is discontinued and aspirin is initiated instead. Initial anticoagulation usually involves intravenous UFH or subcutaneous LMWH for 5-7 days, followed by LMWH or warfarin therapy for 3-6 months. If anticoagulation is not possible, aspirin at a dose of 3-5 mg/kg per day should be used. Surgical repair of heart defects may also be necessary.

For strokes caused by hypercoagulable conditions (other than SCD), anticoagulation with intravenous UFH or subcutaneous LMWH is typically started, following a similar protocol as for cardioembolic stroke. There is no standardized treatment yet for strokes caused by adenosine deaminase 2 deficiency. Because of the heightened risk of HS in these patients, antithrombotic therapy is generally discontinued. Some evidence suggests that tumor necrosis factor inhibitors such as etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, or golimumab, may help reduce stroke recurrence, but more research is needed to establish their safety and effectiveness. Additionally, patients with Fabry disease should be treated with alpha-galactosidase replacement therapy [7].

In children with a cryptogenic ischemic stroke (unknown cause), the exact role of a PFO in causing the stroke or increasing the risk of recurrence remains unclear. Unlike in adults, there is not enough evidence to guide management decisions in children. As a result, the recommended approach is to treat with aspirin at a dose of 3-5 mg/kg per day rather than opting for anticoagulation or percutaneous PFO closure in these cases. Typically, when the cause of ischemic stroke in a child remains unidentified after evaluation, antithrombotic treatment, usually with aspirin, is continued for two years, which corresponds to the period of highest risk for stroke recurrence [6, 44].

For children with SCD who experience stroke, regular blood transfusions are used to keep the percentage of sickled hemoglobin below 30%. However, due to the long-term complications associated with frequent transfusions, bone marrow transplantation from a matched sibling donor is considered the preferred treatment for long-term management.

For children with CVST, treatment starts with anticoagulation using LMWH or UFH, transitioning to oral warfarin for long-term therapy. The goal is to maintain an INR between 2 and 3. Typically, children receive anticoagulation for 5 to 10 days initially, followed by LMWH or warfarin for 3-6 months, provided there is no major bleeding. After three months, imaging can assess whether the veins have reopened; if so, anticoagulation might be stopped. For cases with significant bleeding, follow-up imaging after 5-7 days is advised, continuing anticoagulation if the clot is still growing. In some children, lifelong anticoagulation may be necessary based on the underlying cause. Addressing associated conditions, such as nephrotic syndrome and dehydration, is important, and supplementation with folic acid, vitamin B12, and pyridoxine is recommended in cases of elevated homocysteine levels [45-49].

For children with HS, initial management focuses on stabilizing the patient and providing supportive care [48-51]. Depending on the cause and clinical scenario, treatment might include vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma, or recombinant clotting factor concentrates to manage bleeding. In some cases, surgery or neuro-radiological interventions may be needed to address AV malformations, aneurysms, or other vascular lesions.

Conclusion

Although pediatric stroke is uncommon, it poses significant challenges due to its unique features and wide range of causes, often leading to serious illness and even death. This makes it essential for healthcare providers to remain vigilant. Any child showing sudden focal neurological signs—such as weakness, problems with coordination, speech difficulties, severe headaches, changes in consciousness, or seizures—should be evaluated for stroke. Thanks to advancements in imaging technology, especially MRI, diagnosing stroke in children has become much more accurate, with MRI now considered the gold standard.

For treatment, aspirin is generally recommended early on for AUS unless there are specific reasons to avoid it, like in cases of arterial dissection, cardioembolic stroke, or certain clotting disorders. When stroke is linked to CVST, arterial dissection, cardioembolic causes, or hypercoagulable states, anticoagulation with medications such as low molecular weight heparin (e.g. enoxaparin), UFH, or warfarin is commonly used. While the use of thrombolytic therapy in stroke children is still debated, growing evidence suggests it may be a valuable option in selected cases, offering hope for improved outcomes.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Full-Text: (541 Views)

Introduction

Childhood stroke is a rare but serious medical condition, often leading to significant long-term disabilities or even death. Unlike adult strokes, the causes and risk factors in children are diverse and distinct. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined stroke in 1970 as a “rapidly developed clinical sign of focal (or global) disturbance of cerebral function, lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death, with no apparent cause other than of vascular origin” [1]. Pediatric strokes are generally categorized into perinatal and childhood strokes. Perinatal strokes occur from 28 weeks of gestation up to 28 days after birth. They may present early with symptoms like seizures or encephalopathy, referred to as “acute perinatal strokes”, or later in infancy with signs such as early hand dominance or focal seizures, termed “presumed perinatal strokes”. On the other hand, childhood strokes occur from the age of 28 days to 18 years. Among ischemic stroke types in children, arterial ischemic stroke (AIS) and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) are the most common types, occurring more frequently than pediatric brain malignancies. The annual incidence of AIS is approximately 5 per 100,000 children and affects about 1 in every 2,000 newborns [2]. Hemorrhagic strokes (HSs)—which involve bleeding within or around the brain—account for nearly half of all pediatric stroke cases, with an annual incidence of 1–1.7 per 100,000 children [3]. A large-scale study by deVeber et al. on 1,129 children with AIS reported an annual incidence of 1.72 per 100,000 children, with a significantly higher rate in neonates (10.2 per 100,000). Clinical presentations vary based on age; 88% of neonates had seizures, while 77% of older children presented with focal neurological deficits, and 54% in both groups exhibited more generalized neurological signs. Stroke-related mortality was 5%, and long-term neurological deficits were observed in 60% of neonates and 70% of older children [3]. Kalita et al. examined 79 children aged 1 month to 18 years who had suffered a stroke. Of these children, 62 had AIS, 10 experienced intracerebral hemorrhage, and 7 were diagnosed with CVST [4]. Carey et al. further noted that the incidence of ischemic strokes affecting the brain’s posterior circulation was 0.38 per 100,000 person-years, with a mortality rate of 0.11 per 100,000 person-years [5]. Interestingly, their findings showed a higher incidence in boys than in girls, even after adjusting for trauma and other risk factors. Stroke recurrence is another concern in pediatric populations. Studies suggest that 7-20% of children who experience a stroke may suffer a recurrence over several years of follow-up [6]. This review study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of pediatric stroke, including its risk factors, clinical signs, diagnostic approaches, and management strategies—ultimately to support timely diagnosis and improve outcomes for affected children.

Results

Types of pediatric stroke

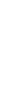

Strokes in children can be categorized into various groups based on their specific characteristics; whether the stroke is ischemic or hemorrhagic, whether it affects the arterial or venous systems, and whether it involves the anterior or posterior circulation of the brain (Figure 1).

Childhood stroke is a rare but serious medical condition, often leading to significant long-term disabilities or even death. Unlike adult strokes, the causes and risk factors in children are diverse and distinct. The World Health Organization (WHO) defined stroke in 1970 as a “rapidly developed clinical sign of focal (or global) disturbance of cerebral function, lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death, with no apparent cause other than of vascular origin” [1]. Pediatric strokes are generally categorized into perinatal and childhood strokes. Perinatal strokes occur from 28 weeks of gestation up to 28 days after birth. They may present early with symptoms like seizures or encephalopathy, referred to as “acute perinatal strokes”, or later in infancy with signs such as early hand dominance or focal seizures, termed “presumed perinatal strokes”. On the other hand, childhood strokes occur from the age of 28 days to 18 years. Among ischemic stroke types in children, arterial ischemic stroke (AIS) and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) are the most common types, occurring more frequently than pediatric brain malignancies. The annual incidence of AIS is approximately 5 per 100,000 children and affects about 1 in every 2,000 newborns [2]. Hemorrhagic strokes (HSs)—which involve bleeding within or around the brain—account for nearly half of all pediatric stroke cases, with an annual incidence of 1–1.7 per 100,000 children [3]. A large-scale study by deVeber et al. on 1,129 children with AIS reported an annual incidence of 1.72 per 100,000 children, with a significantly higher rate in neonates (10.2 per 100,000). Clinical presentations vary based on age; 88% of neonates had seizures, while 77% of older children presented with focal neurological deficits, and 54% in both groups exhibited more generalized neurological signs. Stroke-related mortality was 5%, and long-term neurological deficits were observed in 60% of neonates and 70% of older children [3]. Kalita et al. examined 79 children aged 1 month to 18 years who had suffered a stroke. Of these children, 62 had AIS, 10 experienced intracerebral hemorrhage, and 7 were diagnosed with CVST [4]. Carey et al. further noted that the incidence of ischemic strokes affecting the brain’s posterior circulation was 0.38 per 100,000 person-years, with a mortality rate of 0.11 per 100,000 person-years [5]. Interestingly, their findings showed a higher incidence in boys than in girls, even after adjusting for trauma and other risk factors. Stroke recurrence is another concern in pediatric populations. Studies suggest that 7-20% of children who experience a stroke may suffer a recurrence over several years of follow-up [6]. This review study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of pediatric stroke, including its risk factors, clinical signs, diagnostic approaches, and management strategies—ultimately to support timely diagnosis and improve outcomes for affected children.

Results

Types of pediatric stroke

Strokes in children can be categorized into various groups based on their specific characteristics; whether the stroke is ischemic or hemorrhagic, whether it affects the arterial or venous systems, and whether it involves the anterior or posterior circulation of the brain (Figure 1).

Ischemic strokes in children are typically caused by either thrombotic or embolic events and may affect both arterial and venous blood vessels. In contrast, HSs include all types of non-traumatic bleeding within the skull, excluding intraventricular hemorrhages seen in neonates. These can appear as intraparenchymal (within brain tissue) or subarachnoid hemorrhages (bleeding in the space around the brain). Interestingly, HSs account for about half of all strokes in children, which is much higher than the roughly 15% seen in adults. According to the WHO, transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) and stroke-like episodes are not classified as true strokes. A TIA is defined as a temporary neurological disturbance that resolves within 24 hours. If a stroke-like event is caused by a vascular issue, it is considered a stroke. However, if it stems from other causes (such as metabolic or neurological conditions), it will fall outside this definition [6, 7].

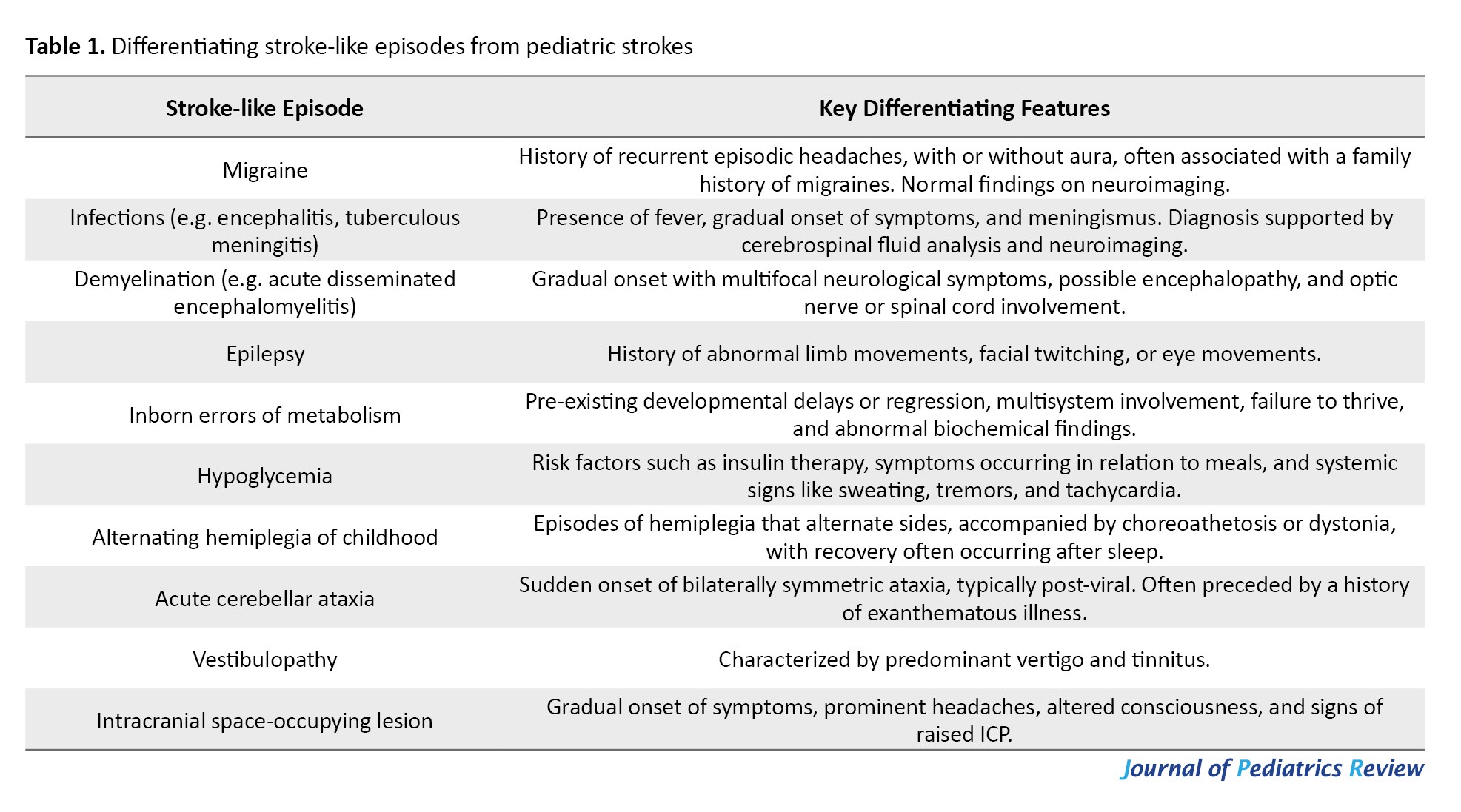

Several conditions can resemble stroke in children, making diagnosis challenging. These include seizures, hypoglycemia, migraines, infections (e.g. meningitis or encephalitis), multiple sclerosis, brain tumors, and metabolic disorders such as MELAS (mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes) [6, 7]. Table I summarizes common pediatric conditions that may be misdiagnosed as strokes, including demyelinating diseases, acute cerebellar ataxia, intracranial masses, and even psychiatric or functional neurological disorders [7].

In a study by Kim et al., 409 patients admitted to the Emergency Department under “code stroke” protocols were assessed. Out of these, 125 children (about 31%) were eventually diagnosed with stroke mimics rather than true strokes. The most frequent mimics included seizures (21.7%), drug toxicity (12.0%), metabolic disturbances (11.2%), brain tumors (8.8%), and peripheral vertigo (7.2%). Risk factors that increased the likelihood of a stroke mimic diagnosis included underlying psychiatric conditions, confusion or altered consciousness, seizure-like activity, and dizziness [8]. Similarly, DeLaroche et al. investigated 59 children who were evaluated using the pediatric stroke clinical pathway. Among them, only 14 were confirmed to have suffered a stroke, while the remaining 45 were diagnosed with stroke mimics. The most common mimicking conditions in this group were functional neurological disorders (20.0%), transient neurological symptoms (17.8%), migraines (15.6%), and seizures (11.1%) [9]. These findings highlight the importance of careful clinical evaluation and appropriate neuroimaging when assessing children with suspected stroke symptoms, as a wide range of other conditions may closely resemble stroke but require very different treatment approaches.

Risk factors of pediatric strokes

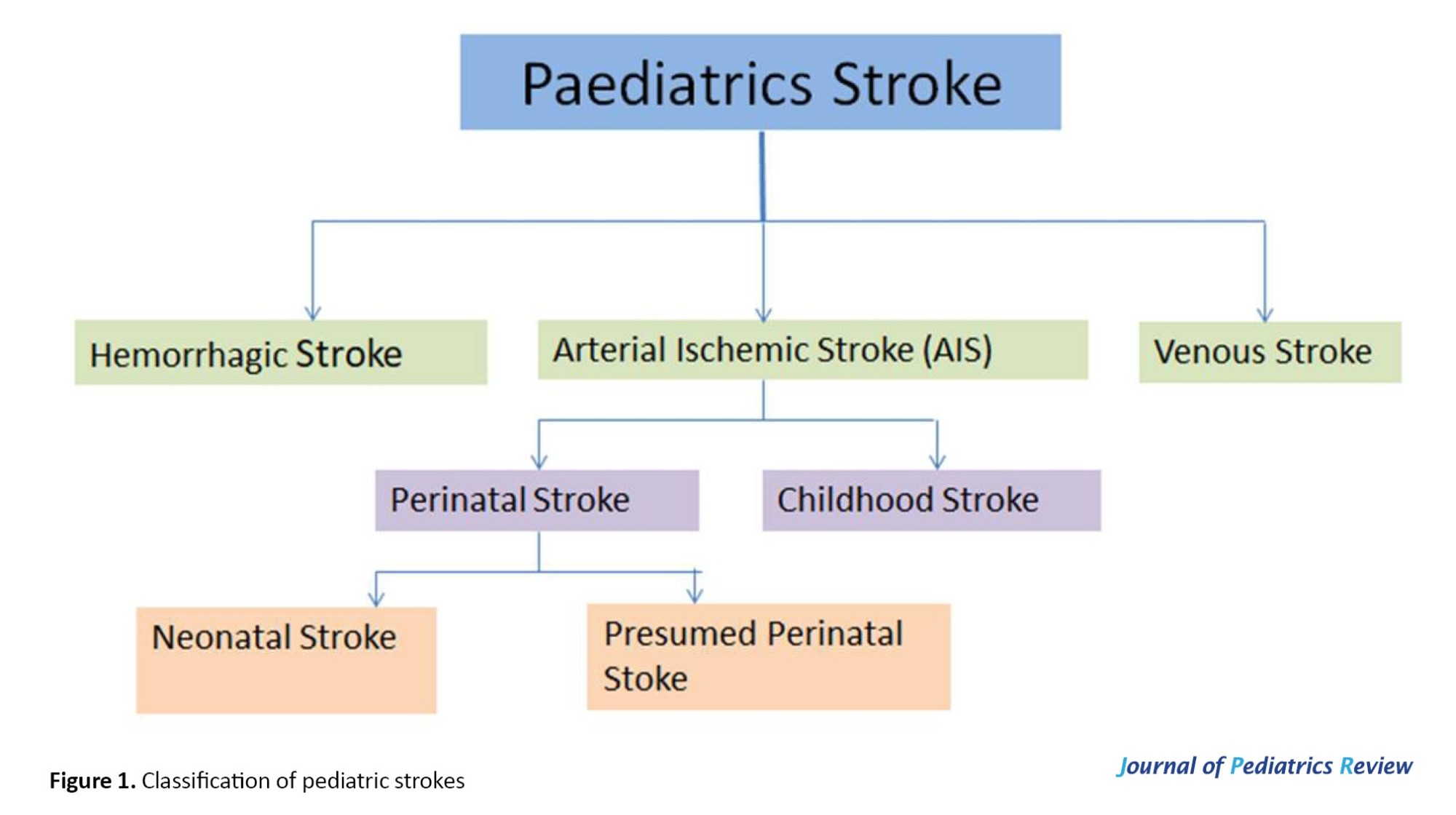

Stroke in children is a complex condition with a wide range of underlying risk factors, including vascular abnormalities (vasculopathies), blood disorders, heart conditions, and clotting issues (coagulopathies). Other risk factors may include infections, kidney disease, autoimmune conditions, metabolic disorders, and head trauma (Figure 2).

Several conditions can resemble stroke in children, making diagnosis challenging. These include seizures, hypoglycemia, migraines, infections (e.g. meningitis or encephalitis), multiple sclerosis, brain tumors, and metabolic disorders such as MELAS (mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes) [6, 7]. Table I summarizes common pediatric conditions that may be misdiagnosed as strokes, including demyelinating diseases, acute cerebellar ataxia, intracranial masses, and even psychiatric or functional neurological disorders [7].

In a study by Kim et al., 409 patients admitted to the Emergency Department under “code stroke” protocols were assessed. Out of these, 125 children (about 31%) were eventually diagnosed with stroke mimics rather than true strokes. The most frequent mimics included seizures (21.7%), drug toxicity (12.0%), metabolic disturbances (11.2%), brain tumors (8.8%), and peripheral vertigo (7.2%). Risk factors that increased the likelihood of a stroke mimic diagnosis included underlying psychiatric conditions, confusion or altered consciousness, seizure-like activity, and dizziness [8]. Similarly, DeLaroche et al. investigated 59 children who were evaluated using the pediatric stroke clinical pathway. Among them, only 14 were confirmed to have suffered a stroke, while the remaining 45 were diagnosed with stroke mimics. The most common mimicking conditions in this group were functional neurological disorders (20.0%), transient neurological symptoms (17.8%), migraines (15.6%), and seizures (11.1%) [9]. These findings highlight the importance of careful clinical evaluation and appropriate neuroimaging when assessing children with suspected stroke symptoms, as a wide range of other conditions may closely resemble stroke but require very different treatment approaches.

Risk factors of pediatric strokes

Stroke in children is a complex condition with a wide range of underlying risk factors, including vascular abnormalities (vasculopathies), blood disorders, heart conditions, and clotting issues (coagulopathies). Other risk factors may include infections, kidney disease, autoimmune conditions, metabolic disorders, and head trauma (Figure 2).

In contrast to adults where stroke is often caused by atherosclerosis or embolism, childhood strokes are typically linked to underlying medical conditions, especially those affecting the heart, blood vessels, or blood composition [10-12].

The most common causes of HS in children are vascular malformations, including arteriovenous (AV) malformations, aneurysms, and cavernomas. During the physical exam, clinicians should check for hemangiomas or other vascular or neurocutaneous signs that might point to an underlying condition. Blood disorders contribute to 10-30% of HSs, and certain substances such as phenylpropanolamine (a nasal decongestant), cocaine, and other illicit drugs can also trigger HSs. While high blood pressure is a well-known risk factor in adults, it plays a less significant role in childhood HS. CVST often occurs alongside childhood infections such as ear infections (otitis media), meningitis, or head trauma. Other risk factors include nephrotic syndrome, dehydration, elevated homocysteine levels, recent brain surgery, malignancies, and medication-induced clotting disorders. Neurosurgical operations near the brain’s venous structures and blockage of the jugular veins can also increase the risk. In newborns, open skull sutures might compress the venous sinuses during or after delivery, especially when lying on their back, raising the risk of CVST.

Cerebral arteriopathy

One of the most common causes of pediatric stroke is cerebral arteriopathy, responsible for nearly 50% of childhood AIS [13]. This refers to diseases causing narrowing or blockage of brain arteries, and includes causes such as arterial dissection, varicella-zoster vasculitis, primary or secondary vasculitis, radiation-induced vasculopathy, genetic conditions (e.g. neurofibromatosis type 1 and trisomy 21), and moyamoya disease/syndrome.

The most frequent form of cerebral arteriopathy in children is focal cerebral arteriopathy, which is often inflammatory in nature and may follow viral infections, especially varicella. It typically presents with unilateral narrowing at the carotid artery trifurcation and usually has a single-phase (monophasic) course [13, 14]. More diffuse or bilateral forms of arteriopathy can be seen in primary central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis or in systemic inflammatory conditions. Another emerging form is the mineralizing angiopathy, which affects the lenticulostriate arteries and is increasingly recognized in younger children. In sickle cell disease (SCD), stroke is a major cause of disability and death, occurring in around 4% of affected children. The risk is highest in the first decade, declines in adolescence, and then increases again in early adulthood [15]. In most SCD-related strokes, arteriopathy is a key factor, often seen alongside moyamoya changes.

Coagulopathies

Coagulation disorders are frequent in pediatric strokes. These may be genetic (e.g. factor V Leiden mutations) or acquired (e.g. antiphospholipid antibody syndrome). Prothrombotic medications, including oral contraceptives and chemotherapy agents like asparaginase, also contribute. Other prothrombotic conditions, such as deficiencies in antithrombin, protein C, and protein S, as well as elevated lipoprotein (a), play significant roles. Vascular malformations, contributing to 40-90% of childhood HS, further increase the risk [16-18].

Congenital heart disease

Congenital heart disease increases the risk of stroke by 19-fold, with ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes occurring due to embolic mechanisms similar to those in adults. Risk factors include arrhythmias, cardiac catheterization, anticoagulation, ventricular assist devices, and corrective surgeries. A thorough cardiovascular evaluation, including electrocardiography and echocardiography, is essential for children with suspected AIS. Studies have identified sepsis, dehydration, hypoxia, acidosis, arteriopathy, and chronic systemic diseases like SCD as prominent risk factors for AIS in children [19-21]. Pangprasertkul et al. [22] conducted a study and identified AIS in 56% of cases and HS in 35.2% of cases. Their discovery revealed that moyamoya disease/syndrome constituted the predominant factor leading to AIS, making up 21.6% of the cases. In contrast, the rupture of cerebral AV malformation emerged as the primary cause of HS, representing 21.9% of the cases. Moreover, it was noted that over one-third (39%) of children exhibited multiple risk factors linked to stroke, with iron deficiency anemia being a prevalent condition in children with AIS, accounting for 39.2% of the cases.

Infections

Certain infections are well-established risk factors for stroke in children. These infections include bacterial meningitis, viral encephalitis, HIV, herpesviruses, especially varicella-zoster virus (VZV), is linked to subcortical strokes affecting areas such as the basal ganglia. Other infectious triggers include tuberculosis, syphilis, influenza A, parvovirus B19, and enteroviruses [23]. These pathogens may lead to stroke through vasculitis, arteriopathy, or in-situ thrombosis.

Oncology-related factors

In children with cancer, stroke risk may stem from the disease itself or its treatment, including radiation and chemotherapy. Drugs such as cytarabine and L-asparaginase have been particularly linked to higher stroke risk. Research has shown that strokes occur in about 3.3% of children with AIS, and in 10.7% of those with CVST during cancer treatment [24-26].

Genetic and hereditary conditions

Several genetic disorders increase the risk of pediatric stroke. These include Fabry disease, homocystinuria, mitochondrial disorders (e.g. MELAS), neurofibromatosis type 1, and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Some strokes are linked to mutations in enzymes such as cystathionine beta-synthase and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, which can result in hyperhomocysteinemia—a condition that promotes vascular damage and early atherosclerosis. These risks are further worsened by vitamin deficiencies in B12 (cyanocobalamin), B6 (pyridoxine), and folate [27-30].

Clinical symptoms of pediatric stroke

The symptoms of pediatric stroke can vary significantly, depending not only on the type of stroke—ischemic or hemorrhagic—but also on the age of the child at the time of onset. In children, the most common sign of ischemic stroke is a focal neurological deficit, typically hemiplegia, which has been reported in up to 94% of cases. However, other acute symptoms may include visual disturbances, speech or language difficulties, sensory loss, and imbalance or coordination issues. In comparison, HSs often present with headaches, vomiting, and reduced consciousness, which are less typical in ischemic events. Seizures are also a frequent presentation, affecting approximately 50% of pediatric stroke cases, regardless of the stroke type or the child’s age [31]. Intraparenchymal HS often presents with symptoms like seizures, vomiting, quickly worsening focal neurological problems, decreased consciousness, and signs of increased pressure inside the skull. On the other hand, subarachnoid HS usually appears suddenly and severely, often starting with a “sentinel” headache (an intense first-time headache) followed by vomiting and altered mental status. Vascular malformations might also cause symptoms such as pulsating sounds in the ears (pulsatile tinnitus), unusual noises heard over the skull (cranial bruit), an enlarged head (macrocephaly), or signs of heart failure due to high blood flow.

The presentation of stroke in children also often varies depending on their age. In neonates and cases of perinatal stroke, early signs may include focal seizures or lethargy within the first few days of life. However, more specific neurological deficits such as hemiparesis may not become evident until weeks or even months later, particularly in presumed perinatal ischemic stroke, which typically presents later in infancy with gradually developing hemiparesis and imaging findings of an old infarct. In infants under one year of age, symptoms can be subtle and include hypotonia, lethargy, apnea, or poor feeding. Toddlers and young children may present with nonspecific signs, such as irritability, vomiting, seizures, or a bulging fontanelle, which suggests increased intracranial pressure (ICP). In contrast, older children and adolescents are more likely to display typical stroke symptoms, such as sudden onset of focal neurological deficits, headache, vomiting, speech disturbances, balance problems, aphasia, visual changes, and altered mental status [32]. CVST is more common in children, particularly newborns. The symptoms can be subtle and vary widely, making the diagnosis challenging but important to recognize because treatment is effective. Children may present with worsening headaches, swelling of the optic disc (papilledema), double vision due to sixth nerve palsies, focal neurological problems, seizures, or confusion.

Diagnostic challenges in young children

Recognizing stroke in younger children can be challenging because their symptoms often appear nonspecific, such as fever, nausea, or unexplained vomiting. However, there are certain red flags that should prompt urgent neurological assessment and immediate neuroimaging. These include the sudden onset of focal seizures, severe or abrupt headaches, noticeable behavioral changes, episodes of loss of consciousness, new-onset ataxia or vertigo, neck stiffness, and the appearance of either transient or persistent focal neurological deficits [6].

Anatomical and vascular patterns of pediatric stroke

In pediatric strokes, the middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory is the most frequently affected, typically resulting in hemiplegia that is more pronounced in the upper limbs, along with hemianopsia and speech or language difficulties. In contrast, strokes involving the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) are more likely to cause weakness in the lower limbs. Posterior circulation strokes, affecting areas supplied by the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) and the vertebrobasilar system, are commonly associated with symptoms such as vertigo, nystagmus, double vision (diplopia), and problems with coordination and balance (ataxia).

Brainstem signs and lesion localization

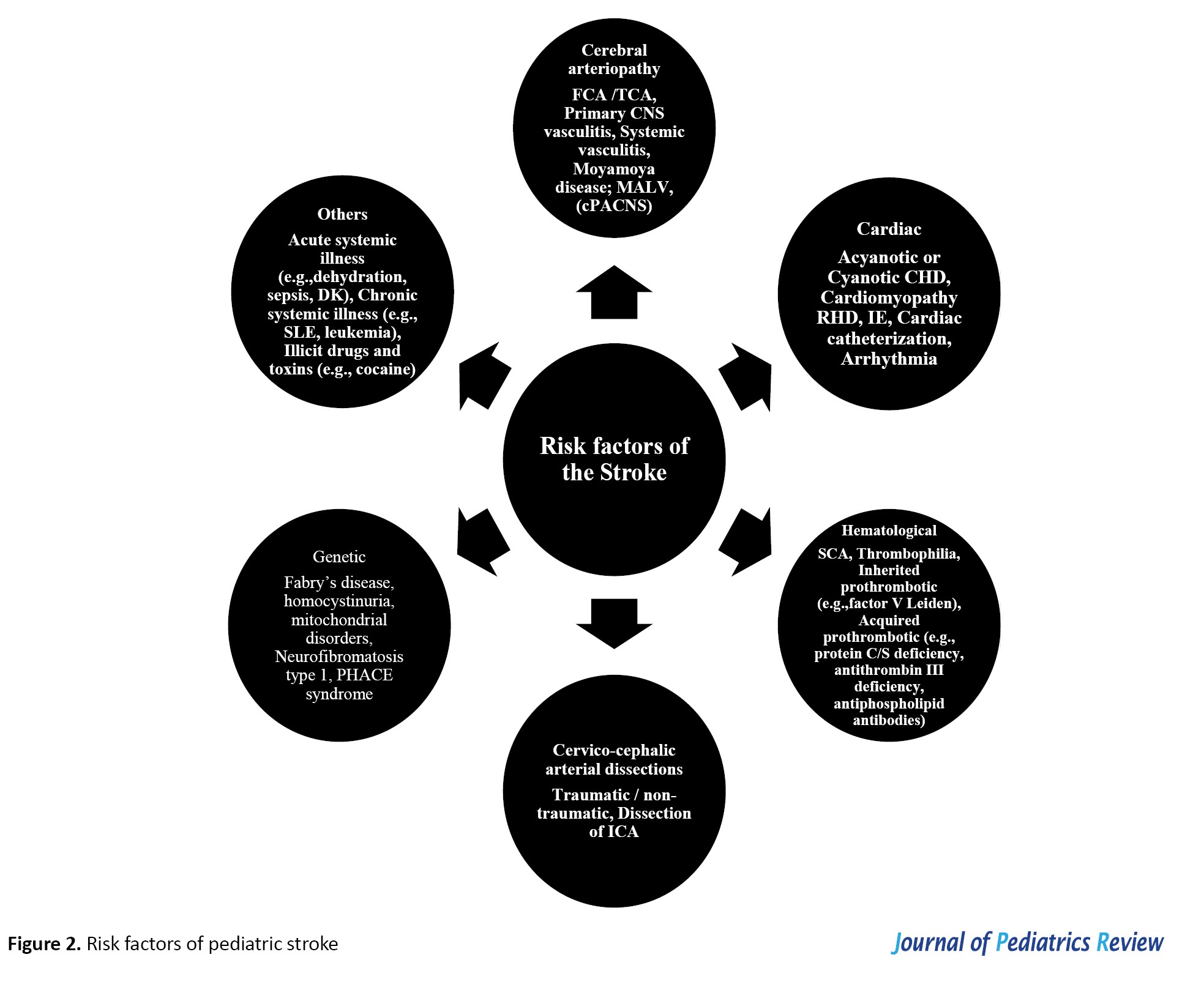

Bulbar dysfunction and dysarthria suggest brainstem lesions, with eye deviation helping localize the lesion. Eye deviation toward the lesion indicates hemispheric involvement, whereas deviation away from the lesion points to brainstem involvement. Focal neurological signs can provide valuable clues about the location of a stroke lesion. When both the cranial nerve deficit and hemiplegia appear on the same side of the body, referred to as uncrossed hemiplegia, which typically points to a supratentorial lesion. In contrast, crossed hemiplegia, where the cranial nerve involvement occurs on one side and the hemiplegia on the opposite side, is more suggestive of a brainstem lesion [33] (Figure 3).

The most common causes of HS in children are vascular malformations, including arteriovenous (AV) malformations, aneurysms, and cavernomas. During the physical exam, clinicians should check for hemangiomas or other vascular or neurocutaneous signs that might point to an underlying condition. Blood disorders contribute to 10-30% of HSs, and certain substances such as phenylpropanolamine (a nasal decongestant), cocaine, and other illicit drugs can also trigger HSs. While high blood pressure is a well-known risk factor in adults, it plays a less significant role in childhood HS. CVST often occurs alongside childhood infections such as ear infections (otitis media), meningitis, or head trauma. Other risk factors include nephrotic syndrome, dehydration, elevated homocysteine levels, recent brain surgery, malignancies, and medication-induced clotting disorders. Neurosurgical operations near the brain’s venous structures and blockage of the jugular veins can also increase the risk. In newborns, open skull sutures might compress the venous sinuses during or after delivery, especially when lying on their back, raising the risk of CVST.

Cerebral arteriopathy

One of the most common causes of pediatric stroke is cerebral arteriopathy, responsible for nearly 50% of childhood AIS [13]. This refers to diseases causing narrowing or blockage of brain arteries, and includes causes such as arterial dissection, varicella-zoster vasculitis, primary or secondary vasculitis, radiation-induced vasculopathy, genetic conditions (e.g. neurofibromatosis type 1 and trisomy 21), and moyamoya disease/syndrome.

The most frequent form of cerebral arteriopathy in children is focal cerebral arteriopathy, which is often inflammatory in nature and may follow viral infections, especially varicella. It typically presents with unilateral narrowing at the carotid artery trifurcation and usually has a single-phase (monophasic) course [13, 14]. More diffuse or bilateral forms of arteriopathy can be seen in primary central nervous system (CNS) vasculitis or in systemic inflammatory conditions. Another emerging form is the mineralizing angiopathy, which affects the lenticulostriate arteries and is increasingly recognized in younger children. In sickle cell disease (SCD), stroke is a major cause of disability and death, occurring in around 4% of affected children. The risk is highest in the first decade, declines in adolescence, and then increases again in early adulthood [15]. In most SCD-related strokes, arteriopathy is a key factor, often seen alongside moyamoya changes.

Coagulopathies

Coagulation disorders are frequent in pediatric strokes. These may be genetic (e.g. factor V Leiden mutations) or acquired (e.g. antiphospholipid antibody syndrome). Prothrombotic medications, including oral contraceptives and chemotherapy agents like asparaginase, also contribute. Other prothrombotic conditions, such as deficiencies in antithrombin, protein C, and protein S, as well as elevated lipoprotein (a), play significant roles. Vascular malformations, contributing to 40-90% of childhood HS, further increase the risk [16-18].

Congenital heart disease

Congenital heart disease increases the risk of stroke by 19-fold, with ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes occurring due to embolic mechanisms similar to those in adults. Risk factors include arrhythmias, cardiac catheterization, anticoagulation, ventricular assist devices, and corrective surgeries. A thorough cardiovascular evaluation, including electrocardiography and echocardiography, is essential for children with suspected AIS. Studies have identified sepsis, dehydration, hypoxia, acidosis, arteriopathy, and chronic systemic diseases like SCD as prominent risk factors for AIS in children [19-21]. Pangprasertkul et al. [22] conducted a study and identified AIS in 56% of cases and HS in 35.2% of cases. Their discovery revealed that moyamoya disease/syndrome constituted the predominant factor leading to AIS, making up 21.6% of the cases. In contrast, the rupture of cerebral AV malformation emerged as the primary cause of HS, representing 21.9% of the cases. Moreover, it was noted that over one-third (39%) of children exhibited multiple risk factors linked to stroke, with iron deficiency anemia being a prevalent condition in children with AIS, accounting for 39.2% of the cases.

Infections

Certain infections are well-established risk factors for stroke in children. These infections include bacterial meningitis, viral encephalitis, HIV, herpesviruses, especially varicella-zoster virus (VZV), is linked to subcortical strokes affecting areas such as the basal ganglia. Other infectious triggers include tuberculosis, syphilis, influenza A, parvovirus B19, and enteroviruses [23]. These pathogens may lead to stroke through vasculitis, arteriopathy, or in-situ thrombosis.

Oncology-related factors

In children with cancer, stroke risk may stem from the disease itself or its treatment, including radiation and chemotherapy. Drugs such as cytarabine and L-asparaginase have been particularly linked to higher stroke risk. Research has shown that strokes occur in about 3.3% of children with AIS, and in 10.7% of those with CVST during cancer treatment [24-26].

Genetic and hereditary conditions

Several genetic disorders increase the risk of pediatric stroke. These include Fabry disease, homocystinuria, mitochondrial disorders (e.g. MELAS), neurofibromatosis type 1, and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Some strokes are linked to mutations in enzymes such as cystathionine beta-synthase and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, which can result in hyperhomocysteinemia—a condition that promotes vascular damage and early atherosclerosis. These risks are further worsened by vitamin deficiencies in B12 (cyanocobalamin), B6 (pyridoxine), and folate [27-30].

Clinical symptoms of pediatric stroke

The symptoms of pediatric stroke can vary significantly, depending not only on the type of stroke—ischemic or hemorrhagic—but also on the age of the child at the time of onset. In children, the most common sign of ischemic stroke is a focal neurological deficit, typically hemiplegia, which has been reported in up to 94% of cases. However, other acute symptoms may include visual disturbances, speech or language difficulties, sensory loss, and imbalance or coordination issues. In comparison, HSs often present with headaches, vomiting, and reduced consciousness, which are less typical in ischemic events. Seizures are also a frequent presentation, affecting approximately 50% of pediatric stroke cases, regardless of the stroke type or the child’s age [31]. Intraparenchymal HS often presents with symptoms like seizures, vomiting, quickly worsening focal neurological problems, decreased consciousness, and signs of increased pressure inside the skull. On the other hand, subarachnoid HS usually appears suddenly and severely, often starting with a “sentinel” headache (an intense first-time headache) followed by vomiting and altered mental status. Vascular malformations might also cause symptoms such as pulsating sounds in the ears (pulsatile tinnitus), unusual noises heard over the skull (cranial bruit), an enlarged head (macrocephaly), or signs of heart failure due to high blood flow.

The presentation of stroke in children also often varies depending on their age. In neonates and cases of perinatal stroke, early signs may include focal seizures or lethargy within the first few days of life. However, more specific neurological deficits such as hemiparesis may not become evident until weeks or even months later, particularly in presumed perinatal ischemic stroke, which typically presents later in infancy with gradually developing hemiparesis and imaging findings of an old infarct. In infants under one year of age, symptoms can be subtle and include hypotonia, lethargy, apnea, or poor feeding. Toddlers and young children may present with nonspecific signs, such as irritability, vomiting, seizures, or a bulging fontanelle, which suggests increased intracranial pressure (ICP). In contrast, older children and adolescents are more likely to display typical stroke symptoms, such as sudden onset of focal neurological deficits, headache, vomiting, speech disturbances, balance problems, aphasia, visual changes, and altered mental status [32]. CVST is more common in children, particularly newborns. The symptoms can be subtle and vary widely, making the diagnosis challenging but important to recognize because treatment is effective. Children may present with worsening headaches, swelling of the optic disc (papilledema), double vision due to sixth nerve palsies, focal neurological problems, seizures, or confusion.

Diagnostic challenges in young children

Recognizing stroke in younger children can be challenging because their symptoms often appear nonspecific, such as fever, nausea, or unexplained vomiting. However, there are certain red flags that should prompt urgent neurological assessment and immediate neuroimaging. These include the sudden onset of focal seizures, severe or abrupt headaches, noticeable behavioral changes, episodes of loss of consciousness, new-onset ataxia or vertigo, neck stiffness, and the appearance of either transient or persistent focal neurological deficits [6].

Anatomical and vascular patterns of pediatric stroke

In pediatric strokes, the middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory is the most frequently affected, typically resulting in hemiplegia that is more pronounced in the upper limbs, along with hemianopsia and speech or language difficulties. In contrast, strokes involving the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) are more likely to cause weakness in the lower limbs. Posterior circulation strokes, affecting areas supplied by the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) and the vertebrobasilar system, are commonly associated with symptoms such as vertigo, nystagmus, double vision (diplopia), and problems with coordination and balance (ataxia).

Brainstem signs and lesion localization

Bulbar dysfunction and dysarthria suggest brainstem lesions, with eye deviation helping localize the lesion. Eye deviation toward the lesion indicates hemispheric involvement, whereas deviation away from the lesion points to brainstem involvement. Focal neurological signs can provide valuable clues about the location of a stroke lesion. When both the cranial nerve deficit and hemiplegia appear on the same side of the body, referred to as uncrossed hemiplegia, which typically points to a supratentorial lesion. In contrast, crossed hemiplegia, where the cranial nerve involvement occurs on one side and the hemiplegia on the opposite side, is more suggestive of a brainstem lesion [33] (Figure 3).

Circulatory considerations in pediatric stroke

The brain receives its blood supply from two major systems: The anterior circulation through the internal carotid arteries, and the posterior circulation via the vertebrobasilar system, both of which meet at the circle of Willis. In children, strokes are more often seen in MCA territory than in the ACA or PCA territories. When the anterior circulation is affected, symptoms depend on which side of the brain is involved. For example, right-sided strokes in right-handed children often cause language difficulties (aphasia), while left-sided strokes more commonly lead to problems with visuospatial perception. Strokes in the posterior circulation tend to cause visual field defects, trouble recognizing colors or objects, double vision (diplopia), dizziness or vertigo, crossed motor signs (meaning brainstem involvement), and balance problems [6, 14]. The differences between anterior and posterior circulation strokes are summarized in Table 2.

Methods of pediatric stroke diagnosis

In the acute setting, brain imaging is a cornerstone of stroke diagnosis in children. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) are the primary tools, with vascular imaging through CT angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) providing essential details about blood vessel involvement. In some cases, advanced techniques like perfusion imaging can be used to assess brain tissue viability. Children at high risk for stroke should undergo immediate neurological assessment followed by urgent imaging. While MRI is the preferred modality, a CT scan—ideally combined with CTA—should be completed within one hour of arrival if MRI is not available [34, 35]. For CVST, when MRI is unavailable, contrast-enhanced CT scans can help, showing classic signs such as the “empty-delta” on contrast CT or the dense triangle sign on plain CT. For HS diagnosis, CT scans are typically the first choice because they are very sensitive in detecting acute bleeding. A thorough evaluation usually involves a CT brain scan combined with CTA, as well as MRI with susceptibility-weighted imaging to detect even small amounts of bleeding. In specialized centers, digital subtraction angiography (DSA) might be performed for a more detailed view. Advanced MRI techniques are very effective at identifying residual blood products after most brain bleeds. Angiographic studies, whether done by CT, MRI, or conventional methods, are important to rule out vascular abnormalities like AV malformations or aneurysms.

CT brain imaging

A CT scan is often the first-line investigation, particularly when an HS is suspected. However, their ability to detect early ischemic changes is limited, especially in the first 12 hours after symptom onset. In fact, over half of children with AIS may have a normal initial CT. That said, CT remains useful in certain settings (e.g. when MRI is unavailable) or for detecting calcifications, such as those seen in mineralizing angiopathy of the lenticulostriate arteries. CTA is often limited to the brain in hemorrhagic cases but can extend to the neck in ischemic events without bleeding. Although CT can reliably detect large infarcts and exclude hemorrhage, MRI is much better at identifying small or early infarcts [36, 37].

MRI brain imaging

MRI, especially when combined with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI), is regarded as the gold standard for diagnosing AIS in children. DWI is particularly valuable because it detects cytotoxic edema early, allowing stroke to be identified even when standard MRI or CT scans appear normal. MRA is also useful in visualizing vascular occlusions, arteriopathies, and abnormalities in blood flow. MRI is highly sensitive in detecting small infarcts, lesions in the posterior fossa, hemorrhagic transformations, multiple infarcts, and flow voids that suggest vessel narrowing or blockage. In cases of AIS, MRA should ideally include imaging from the aortic arch to the vertex of the brain, while in HS cases, imaging may focus on the intracranial vessels. However, since many pediatric patients require sedation or anesthesia for MRI, practical considerations related to safety and logistics are important. If MRI is not possible, CTA serves as a dependable alternative.

Advanced imaging and acute interventions

When AIS is confirmed within 4 hours and HS is ruled out, clinicians may consider thrombolytic therapy with IV tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or mechanical thrombectomy, although these are used with caution due to limited pediatric data. For CVST, a combination of MRI and MR venography is the preferred diagnostic approach.

DSA

DSA remains the most detailed imaging technique for assessing vascular flow, inflammation, aneurysms, and emboli. It is especially valuable in diagnosing moyamoya disease, where it reveals the classic “puff of smoke” appearance. DSA is typically reserved for cases where the cause of stroke is unclear after initial imaging [6].

Additional diagnostic methods

In addition to imaging, a thorough diagnostic evaluation should be done to identify underlying risk factors:

Electroencephalography (EEG): Helps distinguish between seizures, migraines, or other causes of transient neurological symptoms.

Echocardiography: Recommended for all pediatric stroke patients to identify potential cardiac sources of emboli, such as patent foramen ovale (PFO) or ventricular dysfunction.

Hemoglobin electrophoresis: Essential for diagnosing hemoglobinopathies like SCD.

Thrombophilia panel: Evaluation should include screening for both inherited and acquired prothrombotic conditions. This involves testing for deficiencies in protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III, as well as identifying genetic mutations such as factor V Leiden and the prothrombin G20210A mutation. Additionally, the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies should be assessed, along with measuring levels of lipoprotein (a) and homocysteine, as elevations in these markers can increase the risk of thrombotic events.

Infectious and metabolic screening: Important for identifying infections such as VZV, endocarditis, or syphilis that may trigger vascular inflammation or thrombosis.

Immunologic testing: May be necessary in children with suspected autoimmune or immunodeficiency disorders.

Optional investigations: In more complex cases, additional investigations are often necessary to distinguish stroke from other conditions that may present with similar symptoms, as presented in Table 1. A thorough diagnostic workup helps ensure accurate identification and appropriate management of the underlying condition [14, 38, 39].

Pediatric stroke management methods

While pediatric stroke management often draws from adult stroke treatment protocols, it is important to recognize that key differences exist, especially when it comes to acute interventions like anticoagulation, thrombolysis, and mechanical thrombectomy. Due to limited data in children, these treatments require careful consideration and are not routinely recommended. Management should be comprehensive, addressing both acute-phase stabilization and long-term rehabilitation and secondary prevention. A structured approach that balances immediate care with ongoing support is essential for optimizing outcomes in affected children (Table 3).

Acute-phase management methods

Supportive care: Effective management of pediatric stroke begins with stabilizing the basics—ensuring the child’s airway is clear, breathing is adequate, and circulation is stable. To prevent complications such as aspiration, oral intake should be withheld until the swallowing ability is carefully assessed. Maintaining normal body temperature and oxygen levels is critical, and blood sugar should be kept within a safe range, avoiding both low and high extremes. While a modest rise in blood pressure is often tolerated, any low blood pressure must be corrected promptly using intravenous fluids, keeping the head flat when necessary, and employing vasopressors if required.

When cerebral edema occurs due to large ischemic strokes, it can cause dangerous increases in ICP. It is vital to regularly monitor children for signs such as headaches that worsen with position changes, vomiting, irritability or agitation, changes in consciousness, sixth cranial nerve palsy, and swelling of the optic nerve (papilledema). The development of Cushing’s triad—high blood pressure, slow heart rate, and abnormal breathing—signals severe ICP elevation but typically appears in later stages. Managing cerebral edema involves promptly correcting factors such as low oxygen (hypoxia), high carbon dioxide (hypercarbia), and low blood pressure, elevating the head of the bed to about 30 degrees, and ensuring proper head and neck positioning to support venous drainage. For intubated patients, muscle relaxants can control shivering, and pain relief is important to prevent spikes in ICP caused by discomfort. Medical treatments may include carefully controlled hyperventilation to lower carbon dioxide levels, along with hyperosmolar therapies such as intravenous mannitol or hypertonic saline to draw fluid out of the brain. Continuous monitoring of blood osmolarity and electrolytes is essential to avoid complications such as dehydration, low blood pressure, or kidney issues. If these measures fail and ICP remains dangerously high or if there is significant brain swelling causing pressure effects, surgical options like decompressive craniectomy may be necessary [13-41].

Respiratory status and oxygen saturation should be closely observed, and supplemental oxygen should be provided only if levels fall below 95%, since routine oxygen therapy has not been shown to benefit children without hypoxemia. Seizures frequently accompany AISs in children. Unless the child has active seizures or a history of epilepsy, preventative seizure medications are generally not recommended. However, if seizures occur, starting antiseizure drugs—such as levetiracetam—is a reasonable approach during the acute phase. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to support therapeutic hypothermia for pediatric stroke outside of clinical trials. Therefore, cooling strategies should be avoided until more data confirms safety and effectiveness. Once the child is stabilized, early planning for rehabilitation is crucial. Starting physiotherapy and mobilization as soon as possible helps reduce complications such as aspiration pneumonia, bedsores, blood clots, and joint contractures.

Antiplatelet therapy: For most children diagnosed with AIS, starting antiplatelet treatment—usually aspirin at a dose of 3-5 mg per kg per day (up to a maximum of 325 mg daily) within the first 24 hours is generally advised, unless there are contraindications such as bleeding into the brain (hemorrhagic transformation) [13]. It is important to avoid aspirin and other blood-thinning medications during the first day after intravenous thrombolysis, as these can increase bleeding risks. There’s growing evidence that clopidogrel might be a good alternative to aspirin in children, showing similar effectiveness. However, aspirin should never be given during viral illnesses, such as influenza or chickenpox, due to the risk of Reye syndrome, a rare but serious condition.

Anticoagulant therapy: For children with AIS who are considered high-risk, like those with cardioembolic stroke, arterial dissection, or clotting disorders, anticoagulant treatment using heparin or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is typically recommended. LMWH is usually started as soon as the diagnosis is made and continued until these specific risk factors are excluded. A common dosing for enoxaparin, a type of LMWH, is 1 mg/kg given by subcutaneous injection every 12 hours [13].

Recanalization therapy: Recanalization treatments, such as acute thrombolytic therapy or mechanical thrombectomy, might be considered for certain carefully chosen children under 18 who experience AIS. However, there is still limited information available on the safety and effectiveness of these procedures in pediatric patients [13-41]. Case reports have shown positive results in children who meet the same criteria as adults for intravenous thrombolysis. When tPA is given within 4.5 hours after symptom onset, the risk of serious brain bleeding is low [42]. Since pediatric stroke is rare and conducting large trials is difficult, alteplase (a type of tPA) may be considered for adolescents ≥13 years who meet adult treatment guidelines [40]. Although tenecteplase is gaining popularity for adult stroke care, its safety and proper dosing in children have not been well established yet [43]. Therefore, outside of clinical studies, the use of tPA in children with AIS is generally not recommended.

For CVST, the use of tPA has a stronger backing (class II recommendation), as there is better evidence supporting thrombolytic treatment in intravenous strokes among children. A review study suggested that intravenous thrombolysis might be an option for kids aged 1 month to 18 years who meet adult criteria, especially in severe cases involving major artery blockages, significant blood clotting disorders, or basilar artery occlusion with concerning clinical and imaging findings [42].

Mechanical thrombectomy can be considered for children with AIS caused by blockages in large vessels, including the end of the internal carotid artery, the beginning segment of the MCA (M1), or the basilar artery. Although this treatment is backed by level C evidence and carries a class iIb recommendation, its use in pediatric stroke is still debated. While recanalization therapies like thrombectomy are well-established in adult stroke care, their effectiveness and safety in children require further study [13, 40, 41].

Long-term management methods

Neurorehabilitation: Children who survive a stroke require a carefully planned neurorehabilitation program that targets the various challenges they may face, including physical, cognitive, language, behavioral, and adaptive difficulties. Without proper neurorehabilitation, more than half of these children are likely to have lasting neurological problems. Early and consistent use of therapies such as physiotherapy, along with medications to reduce muscle spasticity, plays a crucial role in improving motor function and helping these children regain as much independence as possible after an ischemic stroke [13, 44].

Secondary prevention: The risk of stroke or TIA recurring in children ranges from 7% to 35%, making long-term prevention methods such as antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies a critical focus in ongoing care. In antiplatelet therapy, aspirin is commonly prescribed at a dose of 1-5 mg/kg/day for most cases of ischemic stroke, except when the stroke is caused by cardioembolism, arterial dissection, or an underlying hypercoagulable condition. This treatment is generally maintained for about two years, as this period carries the highest chance of recurrence. In anticoagulant therapy, warfarin is used as one of the most effective options for long-term anticoagulation in children and plays an important role in secondary stroke prevention. Since warfarin takes several days to become fully effective, LMWH is often given initially as a bridge therapy. The typical target international normalized ratio (INR) is between 2 and 3, but for children with mechanical heart valves, a slightly higher INR range of 2.5 to 3.5 is recommended. Warfarin is especially indicated in cases of cardioembolic stroke linked to congenital or acquired heart disease, hypercoagulable disorders, and arterial dissection [13, 45].

Targeted treatments based on underlying causes

Treatment for pediatric AIS is carefully tailored to address the specific cause behind the stroke. For children whose stroke is linked to arteriopathy (except those with adenosine deaminase 2 deficiency), aspirin is preferred over anticoagulants, typically given at 3-5 mg/kg per day, up to a maximum of 81 mg daily. This antithrombotic therapy is usually continued for about two years, as this timeframe carries the highest risk for stroke recurrence. In cases of primary CNS vasculitis, steroids and immunosuppressive treatments may be used to control inflammation.

When stroke results from arterial dissection, treatment generally involves aspirin at 3-5 mg/kg daily or anticoagulation using warfarin or LMWH for 3-6 months. After this initial period, patients usually transition to long-term aspirin therapy. Children and young adults with symptomatic moyamoya disease are often recommended to undergo revascularization surgery. Common surgical options include EDAMS (Encephalo-duro-arterio-myo-synangiosis) or EDASS (Encephalo-duro-arteriosynangiosis), which aim to restore adequate blood flow to the brain.

If a cardioembolic source is suspected, especially in children with complex congenital heart defects, short-term anticoagulation with either LMWH or unfractionated heparin (UFH) is initiated, while vascular imaging and echocardiography are performed to confirm the diagnosis. If no cardioembolic cause is identified, anticoagulation is discontinued and aspirin is initiated instead. Initial anticoagulation usually involves intravenous UFH or subcutaneous LMWH for 5-7 days, followed by LMWH or warfarin therapy for 3-6 months. If anticoagulation is not possible, aspirin at a dose of 3-5 mg/kg per day should be used. Surgical repair of heart defects may also be necessary.

For strokes caused by hypercoagulable conditions (other than SCD), anticoagulation with intravenous UFH or subcutaneous LMWH is typically started, following a similar protocol as for cardioembolic stroke. There is no standardized treatment yet for strokes caused by adenosine deaminase 2 deficiency. Because of the heightened risk of HS in these patients, antithrombotic therapy is generally discontinued. Some evidence suggests that tumor necrosis factor inhibitors such as etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, or golimumab, may help reduce stroke recurrence, but more research is needed to establish their safety and effectiveness. Additionally, patients with Fabry disease should be treated with alpha-galactosidase replacement therapy [7].

In children with a cryptogenic ischemic stroke (unknown cause), the exact role of a PFO in causing the stroke or increasing the risk of recurrence remains unclear. Unlike in adults, there is not enough evidence to guide management decisions in children. As a result, the recommended approach is to treat with aspirin at a dose of 3-5 mg/kg per day rather than opting for anticoagulation or percutaneous PFO closure in these cases. Typically, when the cause of ischemic stroke in a child remains unidentified after evaluation, antithrombotic treatment, usually with aspirin, is continued for two years, which corresponds to the period of highest risk for stroke recurrence [6, 44].

For children with SCD who experience stroke, regular blood transfusions are used to keep the percentage of sickled hemoglobin below 30%. However, due to the long-term complications associated with frequent transfusions, bone marrow transplantation from a matched sibling donor is considered the preferred treatment for long-term management.

For children with CVST, treatment starts with anticoagulation using LMWH or UFH, transitioning to oral warfarin for long-term therapy. The goal is to maintain an INR between 2 and 3. Typically, children receive anticoagulation for 5 to 10 days initially, followed by LMWH or warfarin for 3-6 months, provided there is no major bleeding. After three months, imaging can assess whether the veins have reopened; if so, anticoagulation might be stopped. For cases with significant bleeding, follow-up imaging after 5-7 days is advised, continuing anticoagulation if the clot is still growing. In some children, lifelong anticoagulation may be necessary based on the underlying cause. Addressing associated conditions, such as nephrotic syndrome and dehydration, is important, and supplementation with folic acid, vitamin B12, and pyridoxine is recommended in cases of elevated homocysteine levels [45-49].

For children with HS, initial management focuses on stabilizing the patient and providing supportive care [48-51]. Depending on the cause and clinical scenario, treatment might include vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma, or recombinant clotting factor concentrates to manage bleeding. In some cases, surgery or neuro-radiological interventions may be needed to address AV malformations, aneurysms, or other vascular lesions.

Conclusion

Although pediatric stroke is uncommon, it poses significant challenges due to its unique features and wide range of causes, often leading to serious illness and even death. This makes it essential for healthcare providers to remain vigilant. Any child showing sudden focal neurological signs—such as weakness, problems with coordination, speech difficulties, severe headaches, changes in consciousness, or seizures—should be evaluated for stroke. Thanks to advancements in imaging technology, especially MRI, diagnosing stroke in children has become much more accurate, with MRI now considered the gold standard.