Volume 13, Issue 3 (7-2025)

J. Pediatr. Rev 2025, 13(3): 209-224 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Abbasi G, Khalilnezhadevati M, Karimi M. Factors that Alleviate and Exacerbate Chronic Pain in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Rev 2025; 13 (3) :209-224

URL: http://jpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-751-en.html

URL: http://jpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-751-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Sar.C., Islamic Azad University, Sari, Iran. , gh_abbasi@iausari.ac.ir

2- Department of Psychology, Go.C., Islamic Azad University, Gorgan, Iran.

3- Department of Psychology, Sar.C., Islamic Azad University, Sari, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Go.C., Islamic Azad University, Gorgan, Iran.

3- Department of Psychology, Sar.C., Islamic Azad University, Sari, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 616 kb]

(684 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1180 Views)

Full-Text: (552 Views)

Introduction

Chronic pain is a prevalent and complex issue that, with its unclear etiology and poor response to treatment, presents significant challenges for clinicians and has substantial impacts on an individual’s quality of life and social costs [1]. In children and adolescents, chronic pain refers to pain that persists for more than three months and, unlike acute pain, does not serve a protective function but instead becomes a persistent condition that affects various aspects of life, including education, social relationships, and mental health [2].

The prevalence of chronic pain in both adults and children is alarmingly high [3, 4], imposing significant economic burdens on healthcare systems [5]. However, a comprehensive and accurate classification for chronic pain is still underdeveloped [6]. Although previous systematic reviews have explored various aspects of chronic pain, gaps remain in understanding the intricate interplay between biological, psychological, and social factors. Recent findings highlight newly identified contributors to pain persistence, necessitating an updated review to integrate these insights [7].

Chronic pain among youth involves not only medical concerns but also carries considerable consequences on their societal and financial circumstances [8]. Even with continued interventions, a full recovery remains out of reach for a considerable number of sufferers [9].

When pain transitions into a chronic state, it no longer serves as a protective alert and causes both bodily and emotional complications [10]. Adolescents, in particular, encounter distinct challenges due to developmental transitions, heightened academic demands, and evolving social interactions, all of which can contribute to the persistence and severity of chronic pain [11]. Research indicates that this condition can reduce academic performance, increase drug dependence, and result in school absenteeism and decreased physical activity [4, 12]. Additionally, studies show that children with chronic pain are at a significantly higher risk of developing depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairments compared to their peers [13, 14].

Given the widespread changes in children’s and adolescents’ lifestyles due to technological advancements and the pervasive presence of social networks, chronic pain is expected to become one of the major health challenges of the future [15]. Many factors contribute to chronic pain in children and adolescents. For instance, psychological distress, such as anxiety, can amplify the perception of pain, whereas strong familial support can serve as an exacerbating factor, helping children and adolescents cope more effectively [16, 17]. In order to comprehensively grasp this issue, adopting a model that incorporates biological, psychological, and social dynamics is crucial.

Among these, psychological factors play a crucial role in the experience of pain and the response to treatment. Although physiotherapy efforts have grown, the psychological domain of this problem in the pediatric population has remained relatively neglected [18].

The purpose of this systematic review was to address this deficiency by examining biological, psychological, and social influences to form a more integrated view of chronic pain in younger individuals [11]. Many past studies have mainly concentrated on distinct therapeutic strategies or singular aspects of chronic pain rather than considering a multidimensional perspective. Nonetheless, it is vital to develop a complete framework that includes the interactive roles of biological, psychological, and social dimensions for effective pain care [17].

Newer reviews emphasize the importance of revising population-based data concerning youth chronic pain. The prevalence of chronic pain varies significantly across different demographic groups, and emerging research suggests that socioeconomic and cultural influences play a pivotal role in shaping pain experiences. This review will incorporate the latest findings to enhance the accuracy and depth of understanding regarding chronic pain in children and adolescents [7].

Furthermore, earlier systematic reviews often limited their scope to particular treatments or isolated elements of chronic pain, such as pharmacological or physical interventions. Yet, a holistic model addressing the mutual impact of biological, psychological, and social domains remains essential for adequately managing chronic pain in children and adolescents [17].

This systematic review was designed to overcome these limitations by combining findings related to biological, psychological, and social elements, offering a unified understanding of pain in children and adolescents [11]. Previous reviews have focused on specific treatments or types of pain, but there have been fewer comprehensive reviews that simultaneously examine biological, psychological, and social exacerbating and moderating factors in children with chronic pain. This study aimed to address this gap in the knowledge base.

This review aimed to synthesize these data points to identify the main biological, psychological, and social variables that either worsen or ease chronic pain. Appreciating these multidimensional factors is key to enhancing support measures and optimizing therapeutic strategies for children and adolescent patients.

Methods

This systematic review aimed at identifying and synthesizing studies that explored the alleviating and exacerbating factors of chronic pain in children and adolescents (5 to 18 years).

A comprehensive search was conducted using specialized keywords across multiple English-language databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE, and PsycINFO, and the Google Scholar search engine, covering publications from January 2010 to April 2025. The final search was conducted in April 2025 to ensure the inclusion of the most recent and relevant studies.

Study authors were not approached for further data collection or identification of unpublished work. The search strategy was developed using Boolean operators (AND/OR) to combine relevant keywords, including (“pediatric chronic pain” OR “adolescent chronic pain” OR “persistent pain”) AND (“psychological factors” OR “family functioning” OR “parental distress”) AND (“pain management” OR “biopsychosocial factors”) AND (“systematic review” OR “Risk and protective factors”). In PubMed, searches were conducted without restrictions on study type but were limited to English-language publications between January 2010 and April 2025. The inclusion criteria required studies to focus on children and adolescents aged 5 to 18 years diagnosed with chronic pain lasting more than three months, specifically examining psychological, social, or family-related influences. Eligible studies employed empirical research methods using cross-sectional or longitudinal designs and were published in reputable, peer-reviewed scientific journals in English.

The exclusion criteria eliminated theoretical papers, case studies, and qualitative research, along with studies addressing acute pain or specific medical conditions, such as cancer. Non-English publications were excluded to maintain consistency in data analysis. These criteria were designed to enhance sample homogeneity, ensure a clear focus on psychosocial dimensions rather than medical conditions, and improve the generalizability of findings. While the PICOS framework was not explicitly implemented, its fundamental components, population, exposure, outcome, and study design were implicitly considered.

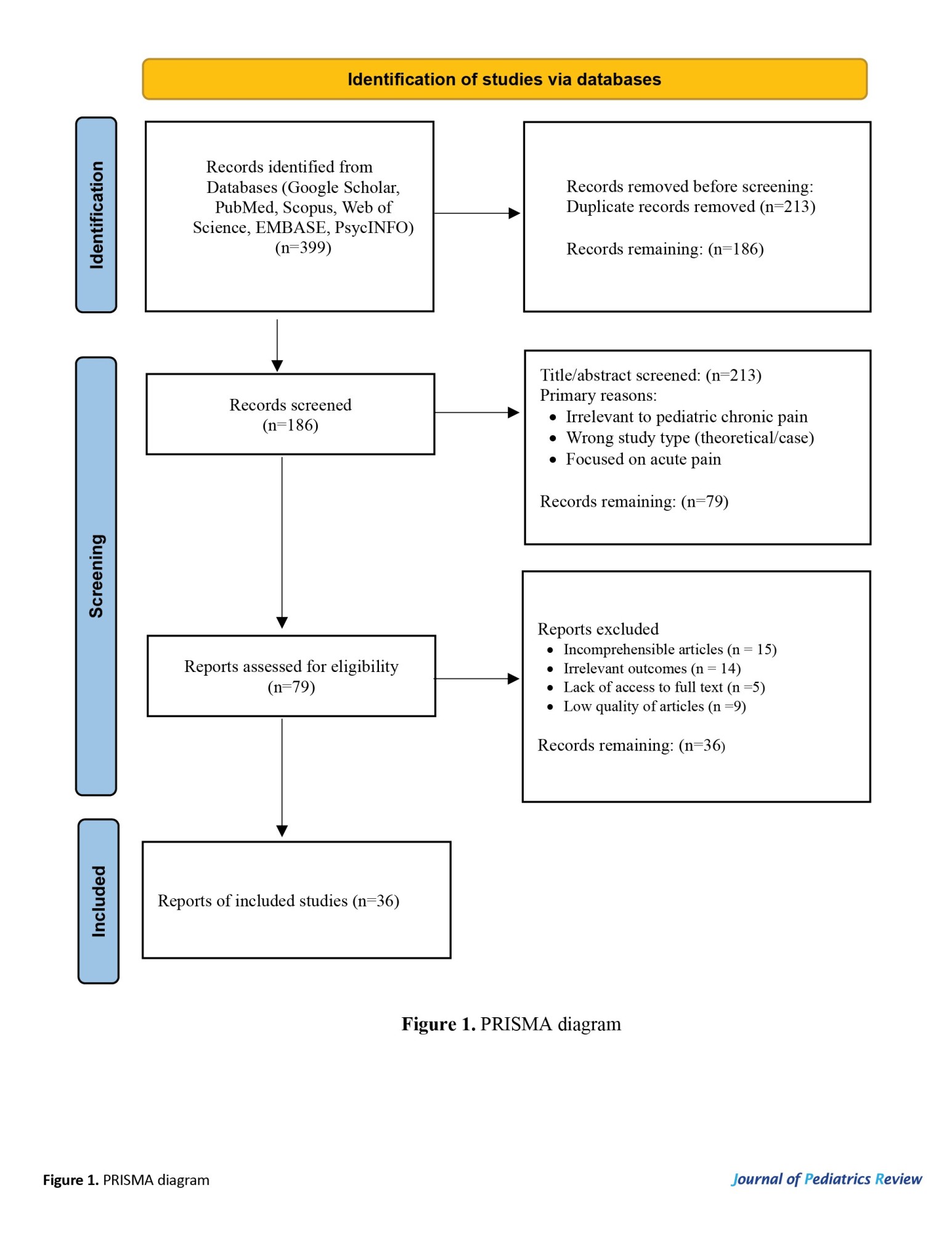

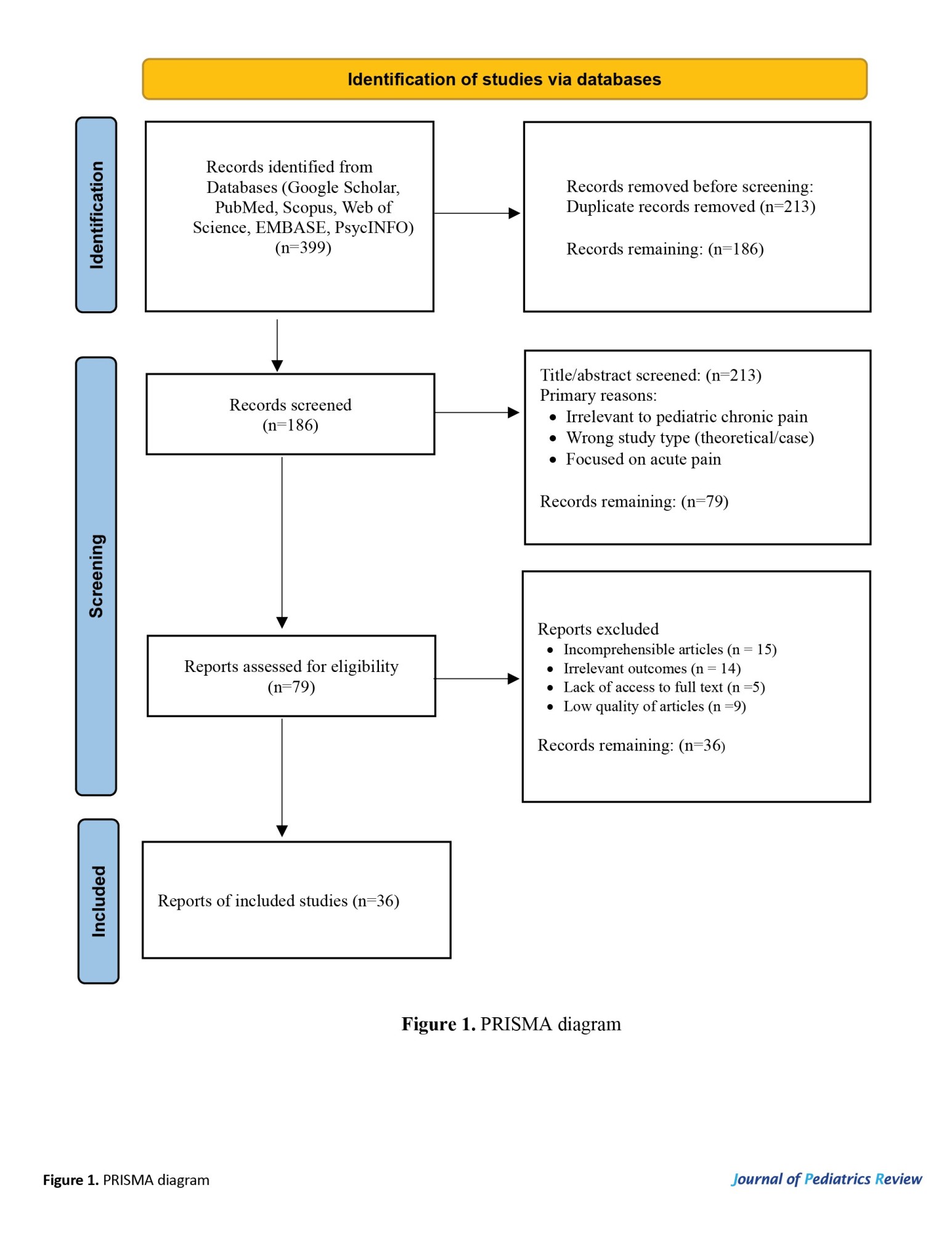

The researchers screened titles and abstracts for relevance. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third researcher. The STROBE checklist was applied to evaluate study quality; each article received a score from 0 to 18, with those under 9 designated as low-quality. Following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flowchart (Figure 1), duplicate articles were removed before two independent reviewers examined the full texts of potentially eligible studies based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. As this review did not involve a meta-analysis, a narrative synthesis approach was applied.

Data extraction was carried out by one researcher using a pre-designed data extraction form, followed by verification by a second researcher to ensure accuracy. Extracted information included study characteristics (authors, year, country, and design), participant details (sample size, age, gender, and type of chronic pain), assessed biological, psychological, social, and family-related variables associated with pain, measurement tools used, and key findings regarding the relationship between these variables and chronic pain. The review assumed consistency in the definition of chronic pain across included articles, as pain lasting over three months, and no follow-up contact was made with study authors to verify or add to the data.

Risk of bias was assessed at the study level using the standardized Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist for quantitative studies, which evaluates factors, such as study design, clarity of inclusion/exclusion criteria, adequacy of data collection methods, and control of confounding variables. Two researchers independently assessed study quality, resolving disagreements through discussion. The findings from the bias assessment were considered in the narrative synthesis, though no statistical weighting was applied, as this review did not include a meta-analysis. Given that most studies were observational, STROBE was used to ensure the adequacy of scientific reporting, methodological legitimacy, and reliability of findings.

Results

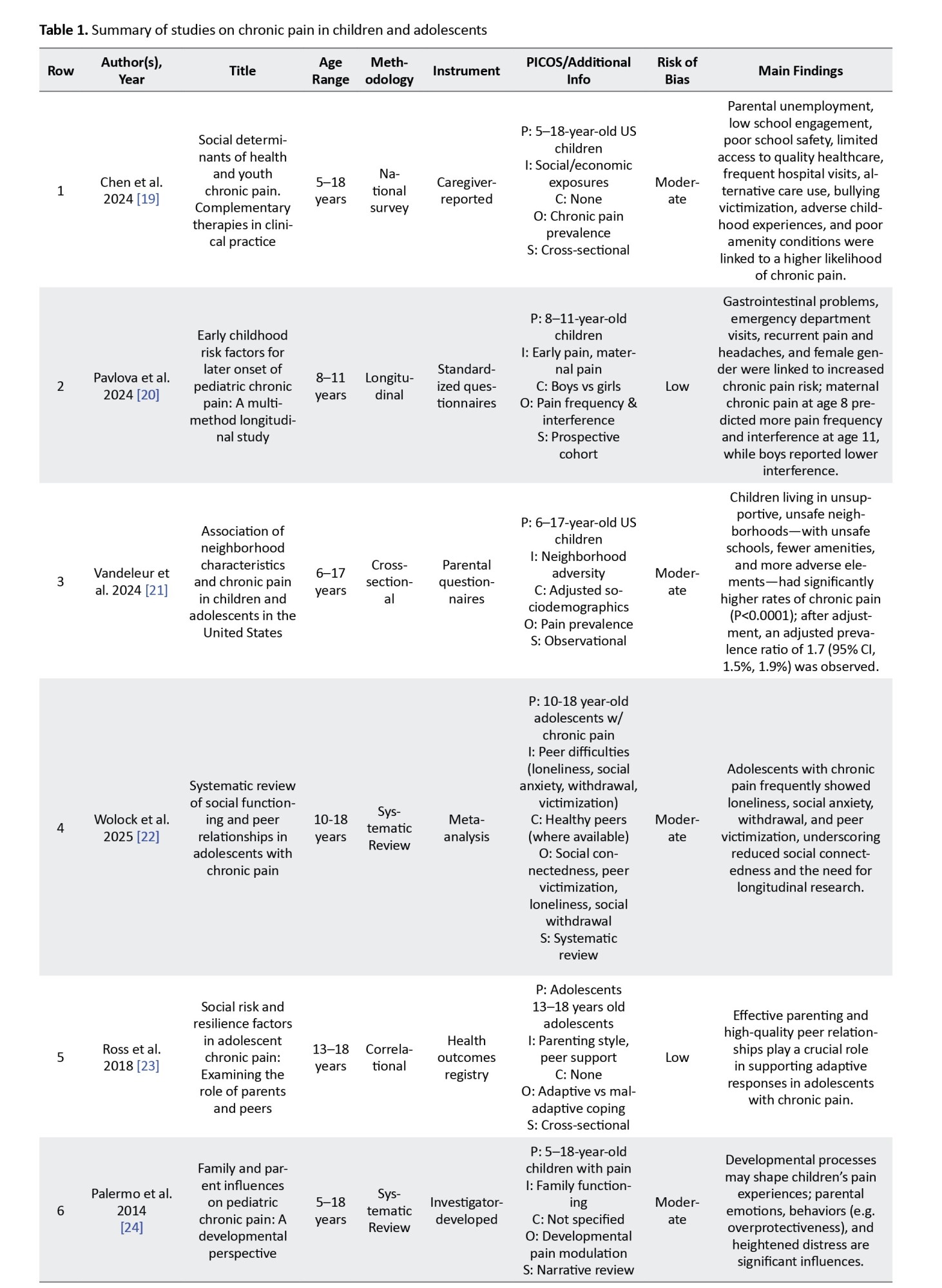

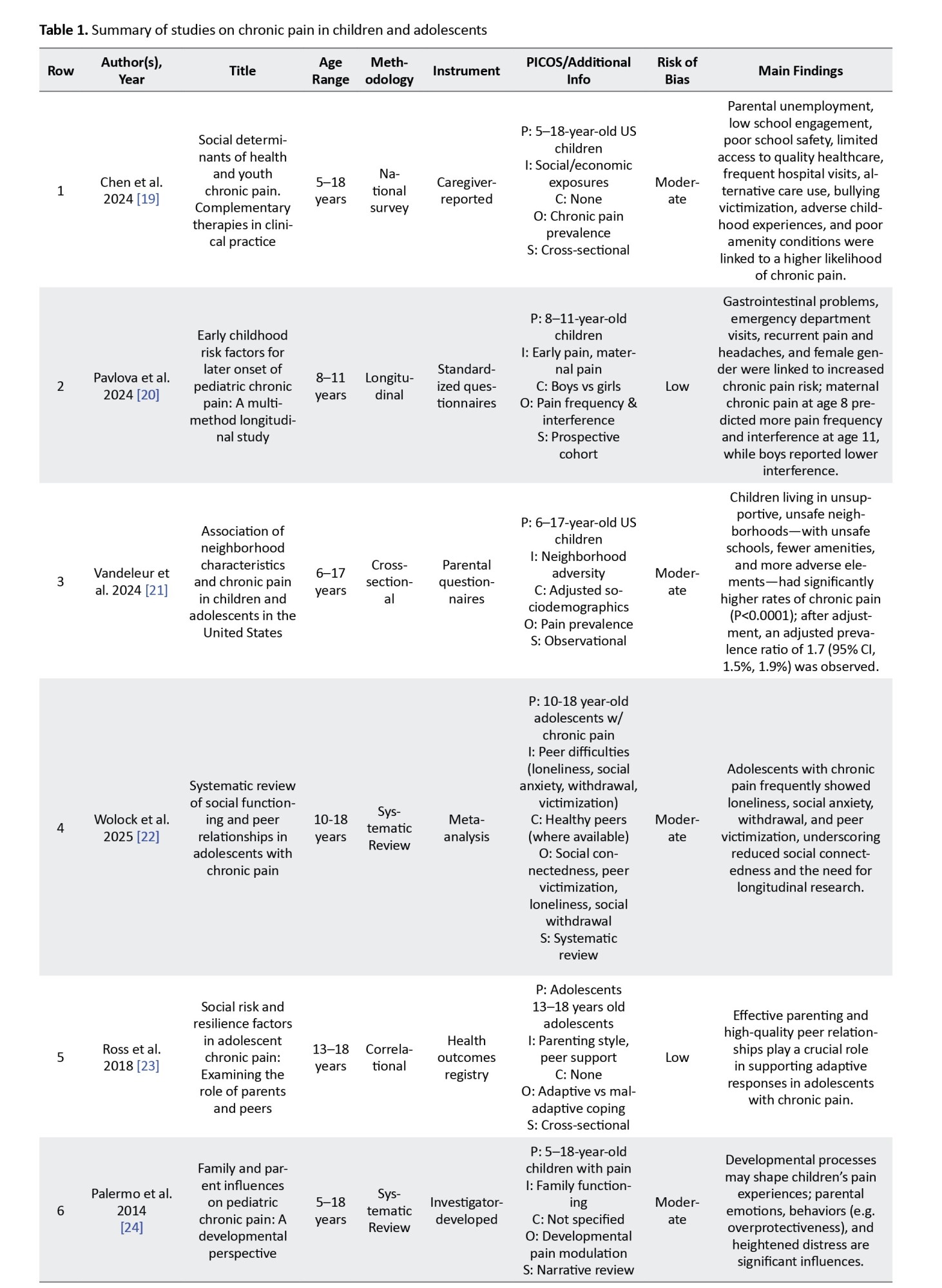

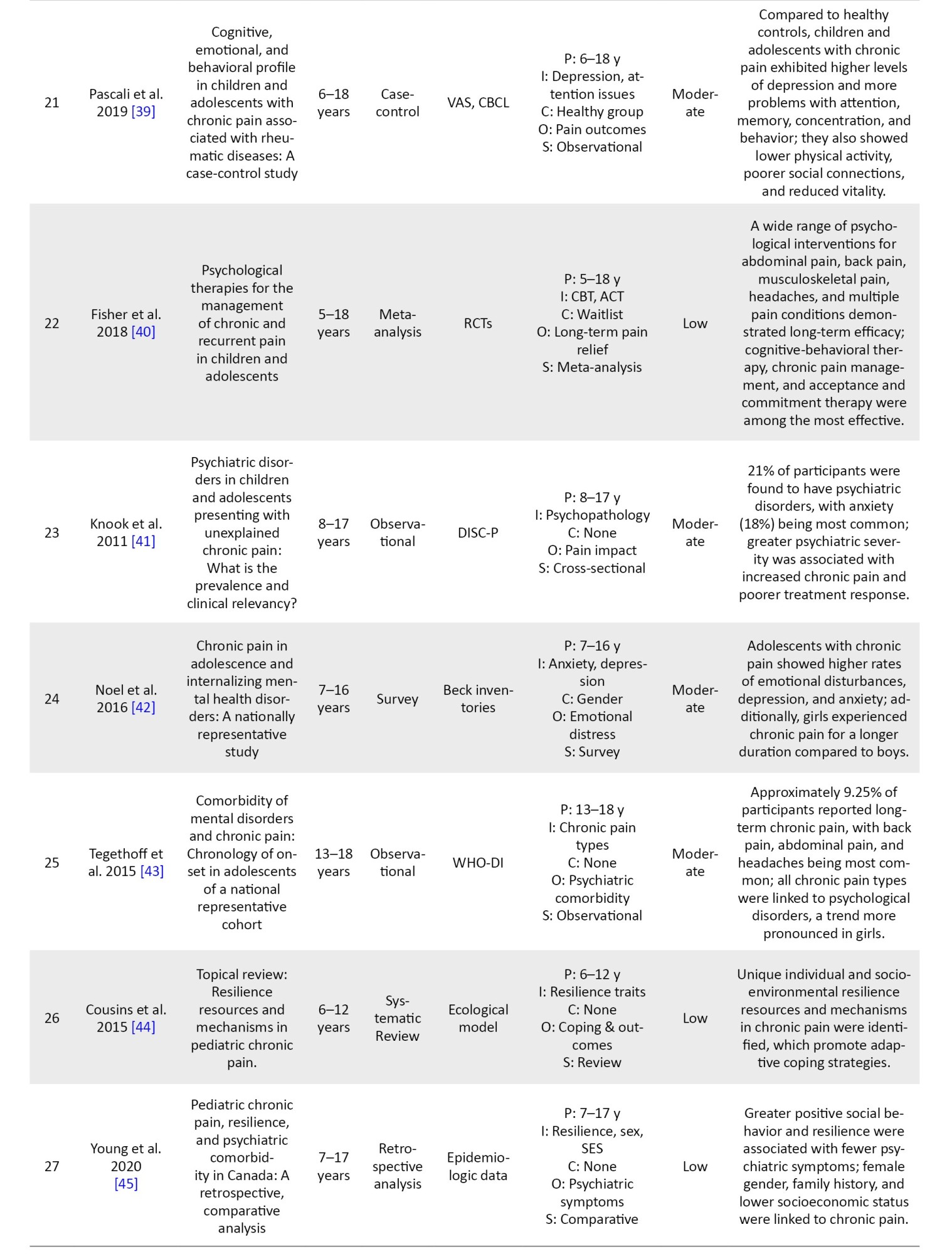

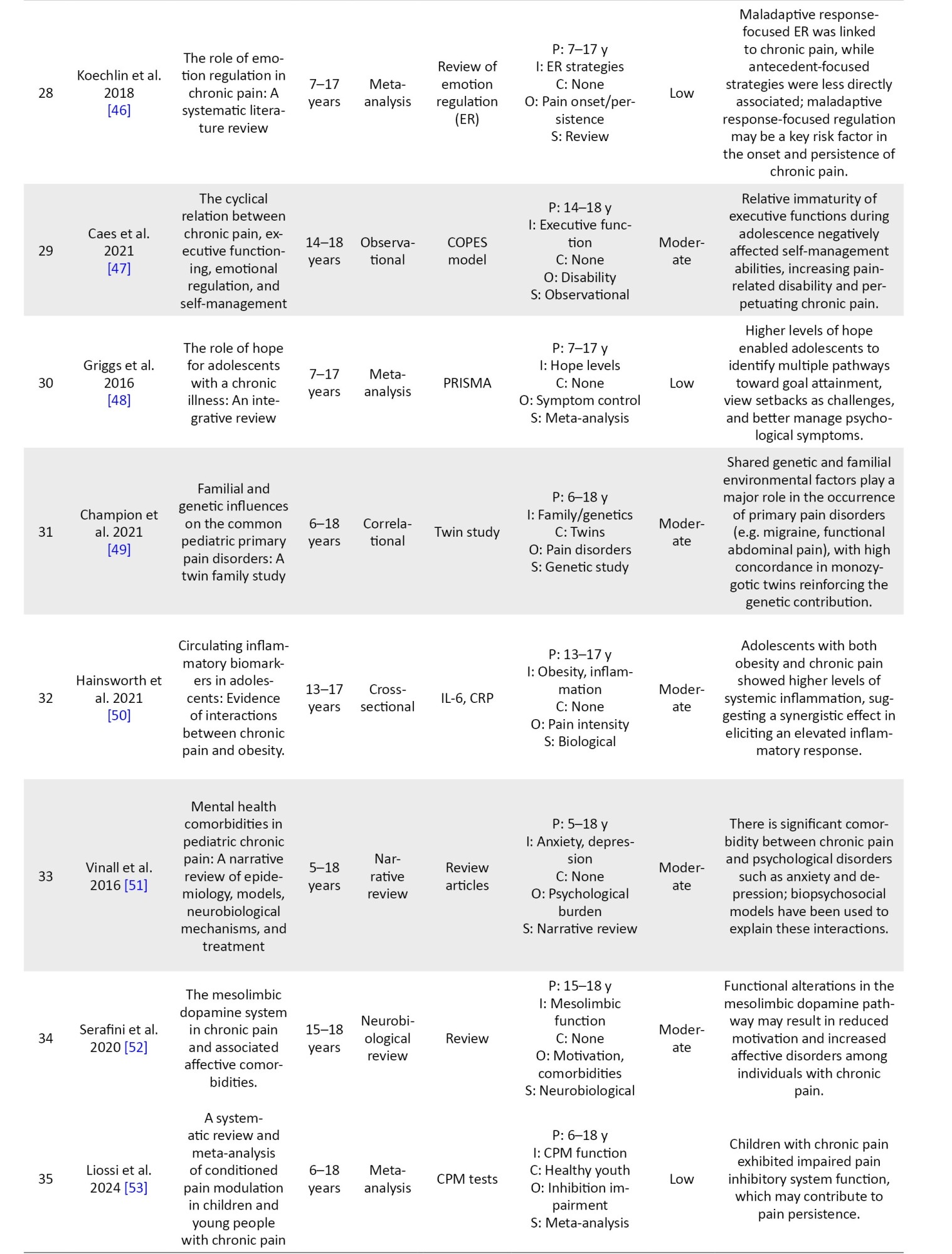

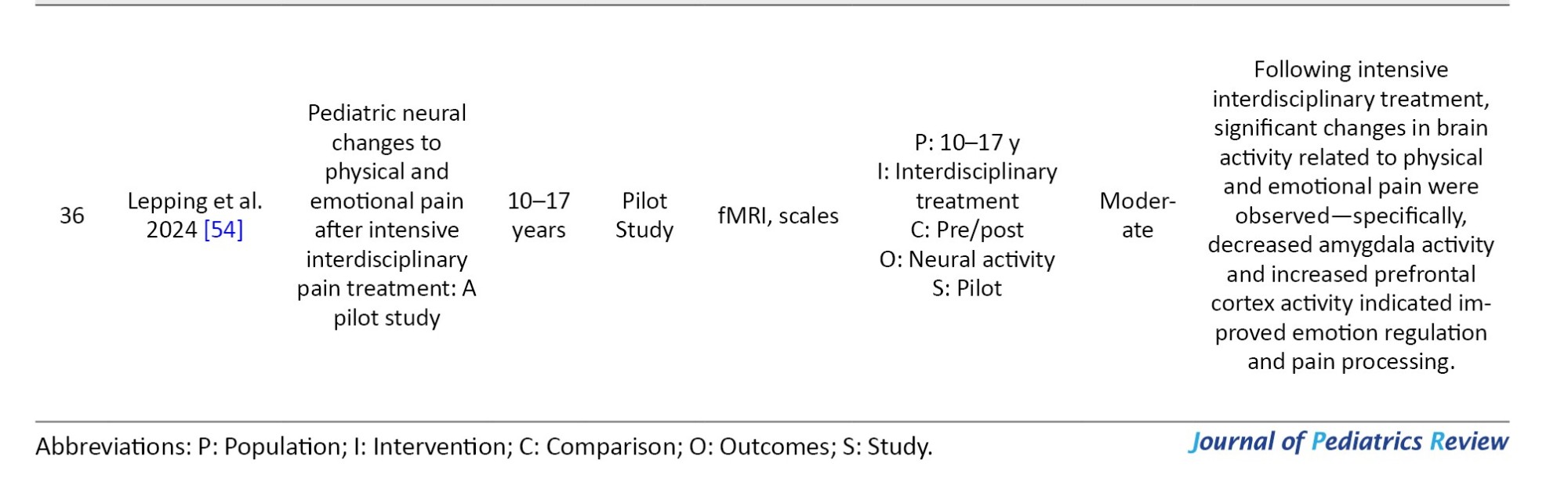

In this review, 36 articles on chronic pain in children and adolescents were classified according to the biopsychosocial model. The biological aspect (9 articles), the psychological aspect (13 articles), and the social aspect (7 articles) were reviewed, and 7 articles were a combination of factors. Overall, the studies emphasized biological, psychological and social factors, and the results highlight the importance of a multidimensional approach to the treatment of chronic pain in children. Overall, the strength of evidence was moderate to high for psychological and social domains, while for biological factors, the evidence strength was moderate.

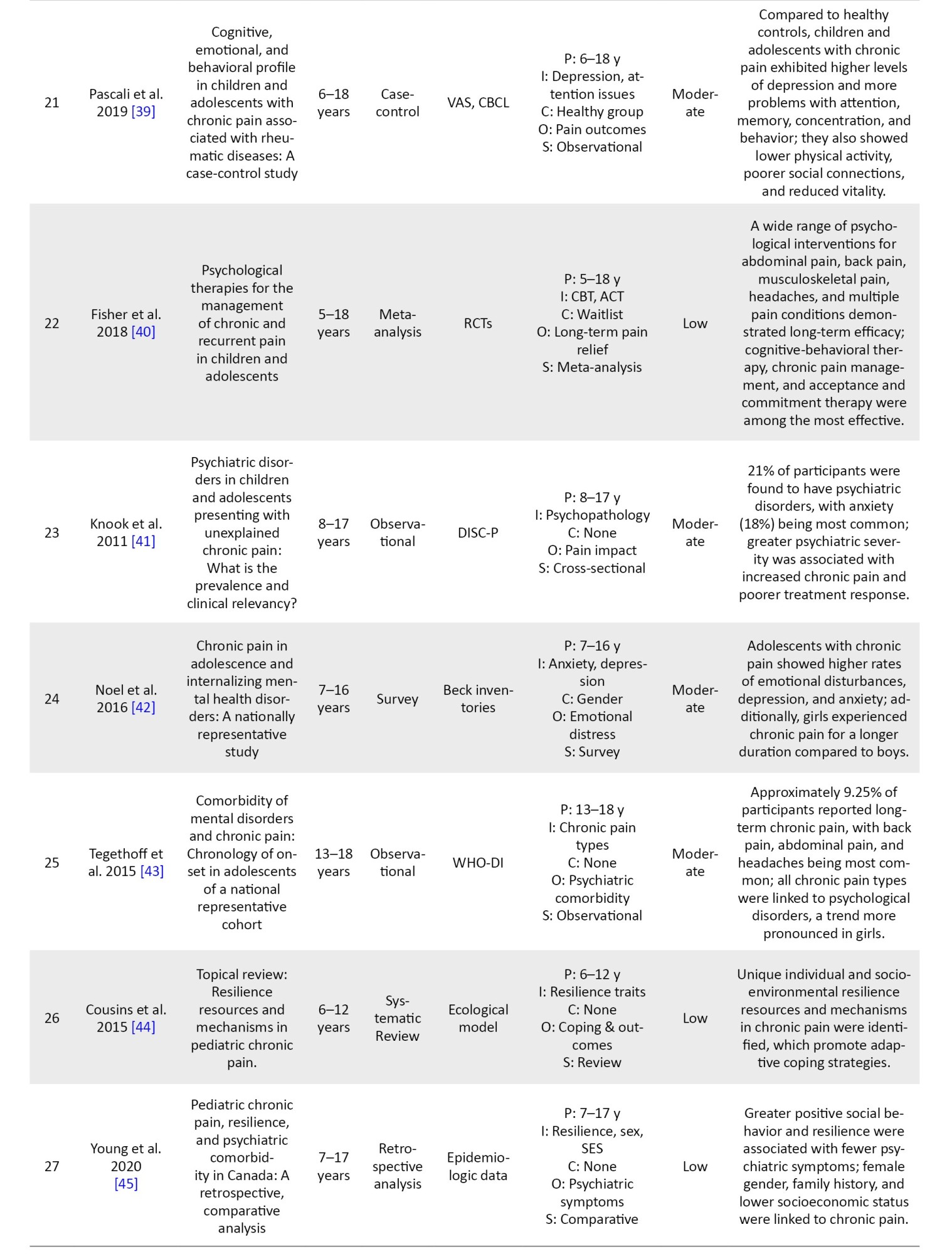

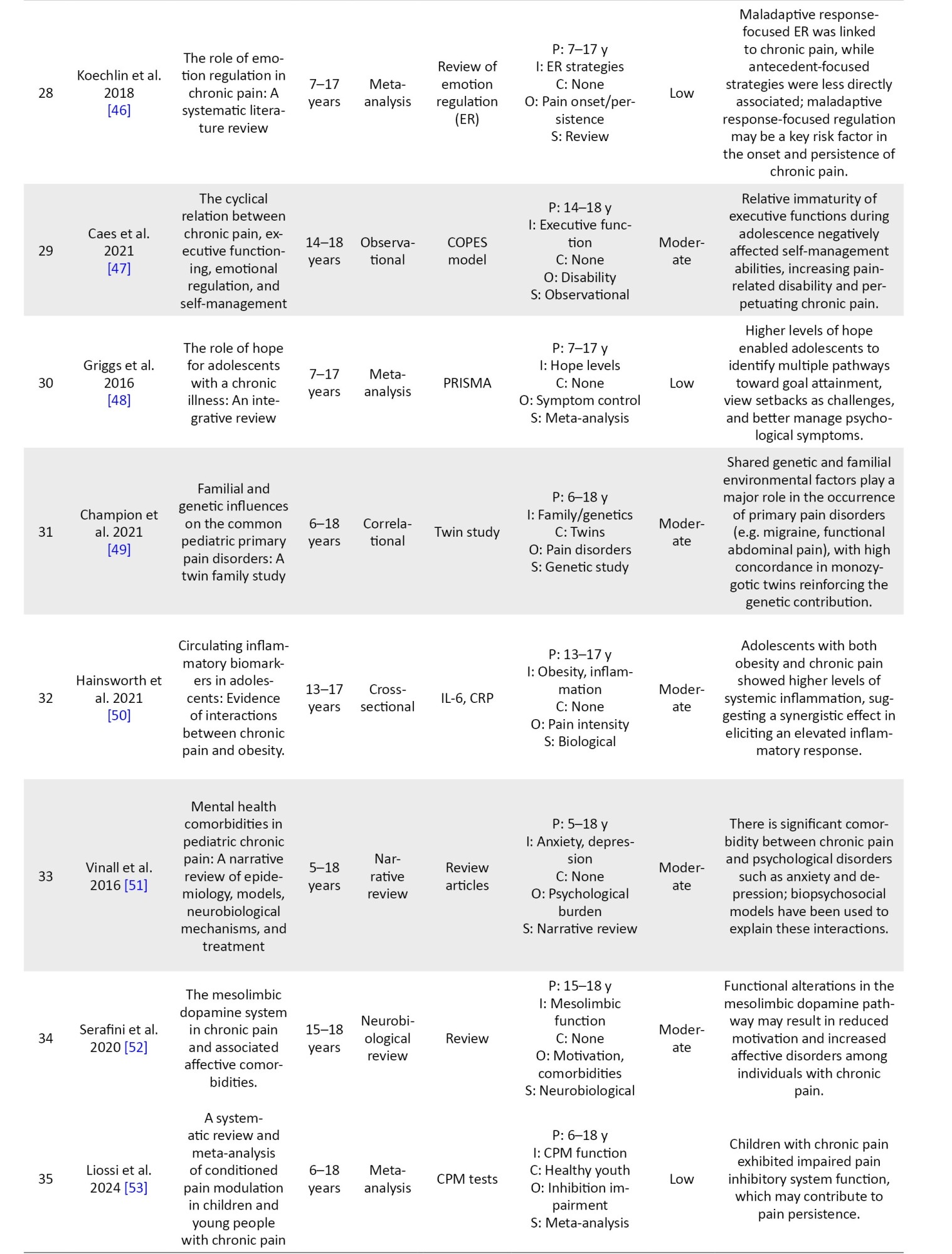

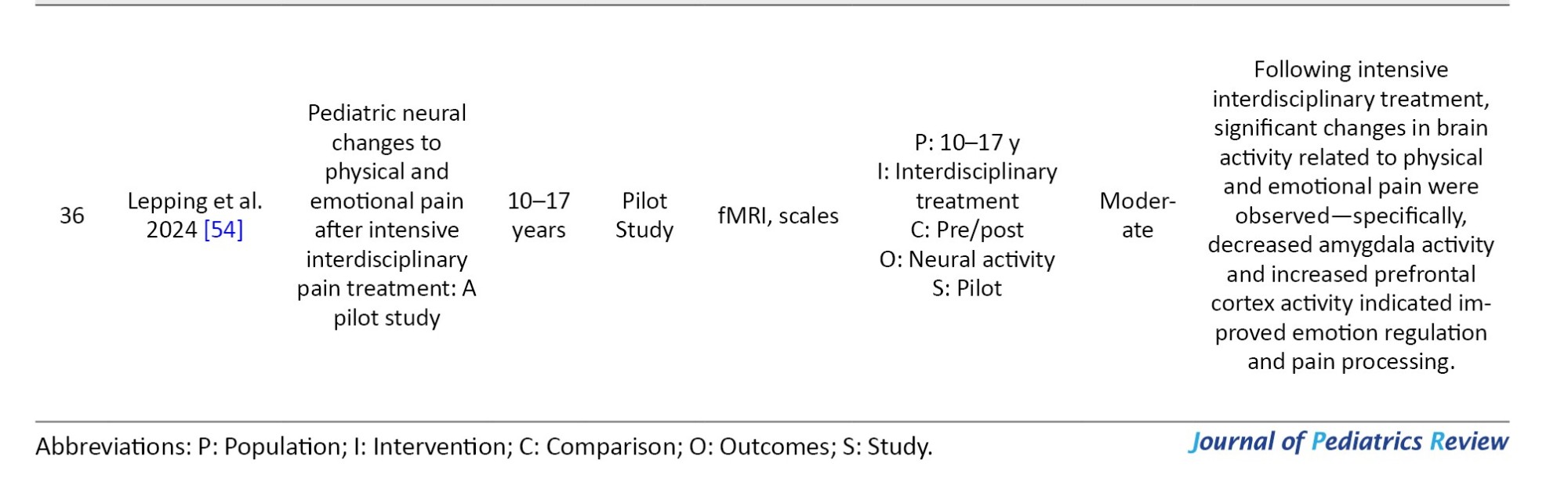

The findings from the reviewed articles on the alleviating and exacerbating factors in chronic pain among children and adolescents are presented in Table 1.

Biological factors

A review of studies shows that biological factors play an important role in chronic pain in children and adolescents. In this regard, several studies have shown that girls are at a higher risk of developing chronic pain. Specifically, research shows that 76% of girls aged 16–18 experience chronic pain [20, 28, 29, 32, 42].

Additionally, dysfunction in endogenous pain inhibitory systems [53], obesity, and systemic inflammation [50]have been identified as contributing factors. Findings also suggest that functional alterations in the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway [52] play a role in exacerbating chronic pain. Among biological factors, neuroplasticity changes [54], aging, and neural system maturation [47] have been recognized as influencing self-regulation of pain.

Psychological factors

Findings from this systematic review indicate that, based on the biopsychosocial model, psychological factors are recognized as both alleviating and exacerbating chronic pain [33].

Among psychological factors, psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and stress [32-36, 38, 39, 51], and pain catastrophizing [26, 33, 35] play a significant role in the onset and persistence of chronic pain. Difficulty with emotion regulation has been highlighted as a critical factor in sustaining chronic pain over time. Psychological factors can act as both alleviating and exacerbating elements depending on how they are regulated or expressed. Other cognitive factors, such as excessive attention to pain [39] and cognitive biases, have been identified as exacerbating factors that influence pain perception.

Additionally, findings suggest that among psychological modulators of chronic pain, resilience, including traits, such as hope [42-44, 23, 44], and access to physical treatments like physiotherapy [30], as well as psychological therapies, such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and pain management programs [40], can significantly support children and adolescents with chronic pain. These approaches enable them to maintain meaningful participation in daily activities despite pain.

Social factors

Findings from the reviewed studies indicate that various social factors contribute to either the exacerbation or moderation of chronic pain in children and adolescents. Among the most significant exacerbating social factors, family-related factors, such as poor family functioning and inappropriate parenting styles (e.g. excessive parental overprotection) [23-26], as well as parental psychological distress and a history of chronic pain [24, 26, 27, 45], have been identified.

School-related contributors, like reduced attendance [19], unsafe environments [19, 21], repeated absences [37], and weak peer relationships [23, 31, 45], have been consistently linked to increased rates of chronic pain. Additionally, from a socioeconomic perspective, documented studies have shown that factors, such as parental unemployment [19], low household income [29], and residence in disadvantaged neighborhoods [21] are correlated with increased prevalence and severity of chronic pain.

Discussion

This study was conducted with the aim of examining exacerbating and moderating factors influencing chronic pain in children and adolescents, with a particular emphasis on the biopsychosocial framework. According to this model, psychological factors play a crucial role in modulating and intensifying chronic pain in pediatric populations. In this context, findings highlight the critical role of psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and stress, in both the initiation and persistence of chronic pain conditions. These affective disorders are linked to increased pain intensity, reduced coping capacity, and lower levels of physical activity, ultimately leading to greater disability, social withdrawal, and functional impairment. These findings are consistent with growing evidence emphasizing that psychological distress and pain symptoms mutually reinforce one another in pediatric populations [32-36, 38, 39, 51].

Among cognitive-affective mechanisms, pain catastrophizing has emerged as a key exacerbating factor. Consistent with previous studies [33, 35], higher levels of catastrophizing were found to be associated with greater pain intensity, increased disability, heightened fear of movement, and diminished quality of life. Catastrophizing perpetuates a maladaptive cycle, wherein negative expectations regarding pain amplify both the sensory and emotional components of pain perception and reinforce avoidance behaviors and social withdrawal [35]. One study noted a weaker link between parental catastrophizing and disability in children, possibly reflecting the influence of factors like parenting style [26].

Emotion regulation difficulties were also identified as critical factors contributing to the persistence of chronic pain. Maladaptive strategies, such as rumination, experiential avoidance, and emotional suppression, were associated with greater disability and poorer psychological outcomes [35, 46]. Conversely, adaptive emotion regulation strategies, including cognitive reappraisal and emotional acceptance, showed a positive correlation with improved functionality and resilience. These results support theoretical models that position emotion regulation at the core of chronic pain maintenance during youth [46].

Among psychological factors, resilience was identified as a significant protective factor, enabling children and adolescents to maintain meaningful engagement in daily activities despite persistent pain. Higher resilience levels were linked to lower anxiety, depression, and stress, as well as more active coping strategies [44, 23, 45].

Optimism, a central component of resilience, may help buffer the negative effects of chronic pain by supporting adaptive emotion regulation and encouraging future-oriented positivity [40].

However, not all studies reported uniform protective effects. Ross et al. found that resilience may only exert its protective benefits in the presence of supportive peer relationships [23], emphasizing the importance of social factors, such as school and peer environments, in shaping resilience outcomes.

Findings further underscore that integrating psychosocial interventions alongside physical treatments may substantially improve patient outcomes. Physical therapies, including physiotherapy [30], and psychological interventions, such as ACT, CBT, and comprehensive pain management programs, have demonstrated potential in fostering acceptance, psychological flexibility, and adaptation [40]. The primary goal of these treatments is to break the negative cognitive-emotional loop and enhance function, highlighting the value of a multimodal strategy in treating pediatric chronic pain.

Individual differences, including age and gender, significantly influence vulnerability to chronic pain. Compared to boys, girls tend to exhibit lower resilience, heightened anxiety, and increased pain severity [55]. Such insights reinforce the importance of customizing psychological support to enhance coping capacity among children and adolescents with chronic pain. Interventions focusing on cognitive training, emotion regulation strategies, and resilience enhancement should be integral components of pain management programs for pediatric populations.

This systematic review also examined the role of social determinants in the amplification and mitigation of chronic pain in children and adolescents. Findings suggest that the social environment exerts a profound influence on the individual’s experience of chronic pain, consistent with the biopsychosocial framework. This model conceptualizes chronic pain as not only biological but also socially shaped, involving variables, like family dynamics, school pressures, friendships, and economic context. The family unit, as a primary social structure, plays a pivotal role in both the development and management of chronic pain in children. This perspective is supported by several studies [23-27], indicating that overprotective or neglectful parenting is tied to more severe pain and poorer adaptability in children [23–26]. These parenting behaviors may reinforce helplessness and dependency, thereby obstructing the development of effective coping strategies. Additionally, parental psychological distress or a history of chronic pain may indirectly exacerbate pain intensity in children by instilling negative pain-related expectations and fostering maladaptive coping responses [23, 24, 26, 27].

The educational environment also constitutes a critical social domain. School disengagement, poor attendance, and unsafe academic settings have all been associated with increased rates of pediatric chronic pain [19, 21, 36]. Likewise, problematic peer dynamics can act as stress triggers, intensifying both pain symptoms and emotional distress in young individuals [23, 31, 56].

Socioeconomic status also exerts a significant influence on chronic pain experiences. Evidence indicates that children living in underprivileged households marked by parental joblessness or low income are more likely to suffer from frequent and intense chronic pain episodes [19, 29, 21]. Mechanisms such as persistent stress, limited access to medical care, and weaker coping skills may explain this socioeconomic link to chronic pain [57, 58]. While socioeconomic status may not directly dictate pain severity, it can shape outcomes by affecting healthcare access and treatment equity [59].

Finally, findings highlight the biological underpinnings of chronic pain, including gender disparities, dysfunctions in endogenous pain inhibition systems, neuroplasticity modifications, neural maturation, obesity-related systemic inflammation, and genetic/epigenetic influences.

One of the most notable biological observations is the elevated risk of chronic pain in girls aged 16–18, with prevalence reaching 76% according to cited studies. Possible explanations for this gender difference include hormonal variability, neural distinctions, and multifactorial biopsychosocial influences [20, 28]. Overall, these insights underscore the need for developmentally tailored biopsychosocial treatment approaches to effectively address chronic pain in children and adolescents.

Conclusion

Chronic pain in children and adolescents is a complex, multifaceted phenomenon shaped by the intricate interplay of biological, psychological, and social determinants. Genetic predispositions, female sex, dysfunction in endogenous pain-inhibitory systems, obesity-related systemic inflammation, alterations in the mesolimbic dopaminergic circuitry, neuroplasticity changes, as well as advancing age and neural maturation may heighten pain sensitivity. At the same time, psychological components, such as emotional distress, catastrophic thinking, difficulties in regulating emotions, levels of resilience, and availability of multidisciplinary interventions, strongly shape both how pain is perceived and how well individuals function.

In addition to personal traits, the social context, including problematic family environments, school-related obstacles, peer interactions, and economic background, plays a crucial role in shaping how children and adolescents experience chronic pain. Findings from this systematic review emphasize the biopsychosocial model as a pivotal framework in understanding chronic pain etiology.

Collectively, the findings underscore the necessity of creating age-appropriate, integrated biopsychosocial approaches that respond comprehensively to the specific needs of children and adolescents. It is essential that future research emphasize long-term and interventional designs to clarify causal relationships and evaluate the effectiveness of evidence-based, multidisciplinary treatments grounded in the biopsychosocial perspective.

Study limitations

Many of the included studies employed cross-sectional designs, which restrict conclusions about causality. There was heterogeneity in measurement tools and definitions across studies, making synthesis and comparison more complex. Additionally, only English-language, peer-reviewed studies were included. This review has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings, potentially introducing language and publication bias. Although study-level risk of bias was assessed using a standardized checklist, bias at the outcome level was not consistently evaluated. Moreover, the exclusion of grey literature and unpublished data might have limited the comprehensiveness of the review.

To overcome these limitations, future studies are recommended to adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to explore causal relationships between biopsychosocial factors and chronic pain. The development of culturally relevant frameworks tailored to non-Western populations and the use of standardized international tools can enhance the comparability of studies. Additionally, integrating physiological data (such as inflammatory markers) with psychosocial factors and focusing on specific subgroups (e.g. adolescents with comorbid disorders) may provide a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms and support the design of personalized interventions. These approaches could pave the way for the development of more comprehensive strategies in managing chronic pain in children and adolescents.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is a systematic review with no human or animal sample.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all individuals whose contributions to literature search and technical guidance supported the development of this review.

References

Chronic pain is a prevalent and complex issue that, with its unclear etiology and poor response to treatment, presents significant challenges for clinicians and has substantial impacts on an individual’s quality of life and social costs [1]. In children and adolescents, chronic pain refers to pain that persists for more than three months and, unlike acute pain, does not serve a protective function but instead becomes a persistent condition that affects various aspects of life, including education, social relationships, and mental health [2].

The prevalence of chronic pain in both adults and children is alarmingly high [3, 4], imposing significant economic burdens on healthcare systems [5]. However, a comprehensive and accurate classification for chronic pain is still underdeveloped [6]. Although previous systematic reviews have explored various aspects of chronic pain, gaps remain in understanding the intricate interplay between biological, psychological, and social factors. Recent findings highlight newly identified contributors to pain persistence, necessitating an updated review to integrate these insights [7].

Chronic pain among youth involves not only medical concerns but also carries considerable consequences on their societal and financial circumstances [8]. Even with continued interventions, a full recovery remains out of reach for a considerable number of sufferers [9].

When pain transitions into a chronic state, it no longer serves as a protective alert and causes both bodily and emotional complications [10]. Adolescents, in particular, encounter distinct challenges due to developmental transitions, heightened academic demands, and evolving social interactions, all of which can contribute to the persistence and severity of chronic pain [11]. Research indicates that this condition can reduce academic performance, increase drug dependence, and result in school absenteeism and decreased physical activity [4, 12]. Additionally, studies show that children with chronic pain are at a significantly higher risk of developing depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairments compared to their peers [13, 14].

Given the widespread changes in children’s and adolescents’ lifestyles due to technological advancements and the pervasive presence of social networks, chronic pain is expected to become one of the major health challenges of the future [15]. Many factors contribute to chronic pain in children and adolescents. For instance, psychological distress, such as anxiety, can amplify the perception of pain, whereas strong familial support can serve as an exacerbating factor, helping children and adolescents cope more effectively [16, 17]. In order to comprehensively grasp this issue, adopting a model that incorporates biological, psychological, and social dynamics is crucial.

Among these, psychological factors play a crucial role in the experience of pain and the response to treatment. Although physiotherapy efforts have grown, the psychological domain of this problem in the pediatric population has remained relatively neglected [18].

The purpose of this systematic review was to address this deficiency by examining biological, psychological, and social influences to form a more integrated view of chronic pain in younger individuals [11]. Many past studies have mainly concentrated on distinct therapeutic strategies or singular aspects of chronic pain rather than considering a multidimensional perspective. Nonetheless, it is vital to develop a complete framework that includes the interactive roles of biological, psychological, and social dimensions for effective pain care [17].

Newer reviews emphasize the importance of revising population-based data concerning youth chronic pain. The prevalence of chronic pain varies significantly across different demographic groups, and emerging research suggests that socioeconomic and cultural influences play a pivotal role in shaping pain experiences. This review will incorporate the latest findings to enhance the accuracy and depth of understanding regarding chronic pain in children and adolescents [7].

Furthermore, earlier systematic reviews often limited their scope to particular treatments or isolated elements of chronic pain, such as pharmacological or physical interventions. Yet, a holistic model addressing the mutual impact of biological, psychological, and social domains remains essential for adequately managing chronic pain in children and adolescents [17].

This systematic review was designed to overcome these limitations by combining findings related to biological, psychological, and social elements, offering a unified understanding of pain in children and adolescents [11]. Previous reviews have focused on specific treatments or types of pain, but there have been fewer comprehensive reviews that simultaneously examine biological, psychological, and social exacerbating and moderating factors in children with chronic pain. This study aimed to address this gap in the knowledge base.

This review aimed to synthesize these data points to identify the main biological, psychological, and social variables that either worsen or ease chronic pain. Appreciating these multidimensional factors is key to enhancing support measures and optimizing therapeutic strategies for children and adolescent patients.

Methods

This systematic review aimed at identifying and synthesizing studies that explored the alleviating and exacerbating factors of chronic pain in children and adolescents (5 to 18 years).

A comprehensive search was conducted using specialized keywords across multiple English-language databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE, and PsycINFO, and the Google Scholar search engine, covering publications from January 2010 to April 2025. The final search was conducted in April 2025 to ensure the inclusion of the most recent and relevant studies.

Study authors were not approached for further data collection or identification of unpublished work. The search strategy was developed using Boolean operators (AND/OR) to combine relevant keywords, including (“pediatric chronic pain” OR “adolescent chronic pain” OR “persistent pain”) AND (“psychological factors” OR “family functioning” OR “parental distress”) AND (“pain management” OR “biopsychosocial factors”) AND (“systematic review” OR “Risk and protective factors”). In PubMed, searches were conducted without restrictions on study type but were limited to English-language publications between January 2010 and April 2025. The inclusion criteria required studies to focus on children and adolescents aged 5 to 18 years diagnosed with chronic pain lasting more than three months, specifically examining psychological, social, or family-related influences. Eligible studies employed empirical research methods using cross-sectional or longitudinal designs and were published in reputable, peer-reviewed scientific journals in English.

The exclusion criteria eliminated theoretical papers, case studies, and qualitative research, along with studies addressing acute pain or specific medical conditions, such as cancer. Non-English publications were excluded to maintain consistency in data analysis. These criteria were designed to enhance sample homogeneity, ensure a clear focus on psychosocial dimensions rather than medical conditions, and improve the generalizability of findings. While the PICOS framework was not explicitly implemented, its fundamental components, population, exposure, outcome, and study design were implicitly considered.

The researchers screened titles and abstracts for relevance. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third researcher. The STROBE checklist was applied to evaluate study quality; each article received a score from 0 to 18, with those under 9 designated as low-quality. Following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flowchart (Figure 1), duplicate articles were removed before two independent reviewers examined the full texts of potentially eligible studies based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. As this review did not involve a meta-analysis, a narrative synthesis approach was applied.

Data extraction was carried out by one researcher using a pre-designed data extraction form, followed by verification by a second researcher to ensure accuracy. Extracted information included study characteristics (authors, year, country, and design), participant details (sample size, age, gender, and type of chronic pain), assessed biological, psychological, social, and family-related variables associated with pain, measurement tools used, and key findings regarding the relationship between these variables and chronic pain. The review assumed consistency in the definition of chronic pain across included articles, as pain lasting over three months, and no follow-up contact was made with study authors to verify or add to the data.

Risk of bias was assessed at the study level using the standardized Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist for quantitative studies, which evaluates factors, such as study design, clarity of inclusion/exclusion criteria, adequacy of data collection methods, and control of confounding variables. Two researchers independently assessed study quality, resolving disagreements through discussion. The findings from the bias assessment were considered in the narrative synthesis, though no statistical weighting was applied, as this review did not include a meta-analysis. Given that most studies were observational, STROBE was used to ensure the adequacy of scientific reporting, methodological legitimacy, and reliability of findings.

Results

In this review, 36 articles on chronic pain in children and adolescents were classified according to the biopsychosocial model. The biological aspect (9 articles), the psychological aspect (13 articles), and the social aspect (7 articles) were reviewed, and 7 articles were a combination of factors. Overall, the studies emphasized biological, psychological and social factors, and the results highlight the importance of a multidimensional approach to the treatment of chronic pain in children. Overall, the strength of evidence was moderate to high for psychological and social domains, while for biological factors, the evidence strength was moderate.

The findings from the reviewed articles on the alleviating and exacerbating factors in chronic pain among children and adolescents are presented in Table 1.

Biological factors

A review of studies shows that biological factors play an important role in chronic pain in children and adolescents. In this regard, several studies have shown that girls are at a higher risk of developing chronic pain. Specifically, research shows that 76% of girls aged 16–18 experience chronic pain [20, 28, 29, 32, 42].

Additionally, dysfunction in endogenous pain inhibitory systems [53], obesity, and systemic inflammation [50]have been identified as contributing factors. Findings also suggest that functional alterations in the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway [52] play a role in exacerbating chronic pain. Among biological factors, neuroplasticity changes [54], aging, and neural system maturation [47] have been recognized as influencing self-regulation of pain.

Psychological factors

Findings from this systematic review indicate that, based on the biopsychosocial model, psychological factors are recognized as both alleviating and exacerbating chronic pain [33].

Among psychological factors, psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and stress [32-36, 38, 39, 51], and pain catastrophizing [26, 33, 35] play a significant role in the onset and persistence of chronic pain. Difficulty with emotion regulation has been highlighted as a critical factor in sustaining chronic pain over time. Psychological factors can act as both alleviating and exacerbating elements depending on how they are regulated or expressed. Other cognitive factors, such as excessive attention to pain [39] and cognitive biases, have been identified as exacerbating factors that influence pain perception.

Additionally, findings suggest that among psychological modulators of chronic pain, resilience, including traits, such as hope [42-44, 23, 44], and access to physical treatments like physiotherapy [30], as well as psychological therapies, such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and pain management programs [40], can significantly support children and adolescents with chronic pain. These approaches enable them to maintain meaningful participation in daily activities despite pain.

Social factors

Findings from the reviewed studies indicate that various social factors contribute to either the exacerbation or moderation of chronic pain in children and adolescents. Among the most significant exacerbating social factors, family-related factors, such as poor family functioning and inappropriate parenting styles (e.g. excessive parental overprotection) [23-26], as well as parental psychological distress and a history of chronic pain [24, 26, 27, 45], have been identified.

School-related contributors, like reduced attendance [19], unsafe environments [19, 21], repeated absences [37], and weak peer relationships [23, 31, 45], have been consistently linked to increased rates of chronic pain. Additionally, from a socioeconomic perspective, documented studies have shown that factors, such as parental unemployment [19], low household income [29], and residence in disadvantaged neighborhoods [21] are correlated with increased prevalence and severity of chronic pain.

Discussion

This study was conducted with the aim of examining exacerbating and moderating factors influencing chronic pain in children and adolescents, with a particular emphasis on the biopsychosocial framework. According to this model, psychological factors play a crucial role in modulating and intensifying chronic pain in pediatric populations. In this context, findings highlight the critical role of psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and stress, in both the initiation and persistence of chronic pain conditions. These affective disorders are linked to increased pain intensity, reduced coping capacity, and lower levels of physical activity, ultimately leading to greater disability, social withdrawal, and functional impairment. These findings are consistent with growing evidence emphasizing that psychological distress and pain symptoms mutually reinforce one another in pediatric populations [32-36, 38, 39, 51].

Among cognitive-affective mechanisms, pain catastrophizing has emerged as a key exacerbating factor. Consistent with previous studies [33, 35], higher levels of catastrophizing were found to be associated with greater pain intensity, increased disability, heightened fear of movement, and diminished quality of life. Catastrophizing perpetuates a maladaptive cycle, wherein negative expectations regarding pain amplify both the sensory and emotional components of pain perception and reinforce avoidance behaviors and social withdrawal [35]. One study noted a weaker link between parental catastrophizing and disability in children, possibly reflecting the influence of factors like parenting style [26].

Emotion regulation difficulties were also identified as critical factors contributing to the persistence of chronic pain. Maladaptive strategies, such as rumination, experiential avoidance, and emotional suppression, were associated with greater disability and poorer psychological outcomes [35, 46]. Conversely, adaptive emotion regulation strategies, including cognitive reappraisal and emotional acceptance, showed a positive correlation with improved functionality and resilience. These results support theoretical models that position emotion regulation at the core of chronic pain maintenance during youth [46].

Among psychological factors, resilience was identified as a significant protective factor, enabling children and adolescents to maintain meaningful engagement in daily activities despite persistent pain. Higher resilience levels were linked to lower anxiety, depression, and stress, as well as more active coping strategies [44, 23, 45].

Optimism, a central component of resilience, may help buffer the negative effects of chronic pain by supporting adaptive emotion regulation and encouraging future-oriented positivity [40].

However, not all studies reported uniform protective effects. Ross et al. found that resilience may only exert its protective benefits in the presence of supportive peer relationships [23], emphasizing the importance of social factors, such as school and peer environments, in shaping resilience outcomes.

Findings further underscore that integrating psychosocial interventions alongside physical treatments may substantially improve patient outcomes. Physical therapies, including physiotherapy [30], and psychological interventions, such as ACT, CBT, and comprehensive pain management programs, have demonstrated potential in fostering acceptance, psychological flexibility, and adaptation [40]. The primary goal of these treatments is to break the negative cognitive-emotional loop and enhance function, highlighting the value of a multimodal strategy in treating pediatric chronic pain.

Individual differences, including age and gender, significantly influence vulnerability to chronic pain. Compared to boys, girls tend to exhibit lower resilience, heightened anxiety, and increased pain severity [55]. Such insights reinforce the importance of customizing psychological support to enhance coping capacity among children and adolescents with chronic pain. Interventions focusing on cognitive training, emotion regulation strategies, and resilience enhancement should be integral components of pain management programs for pediatric populations.

This systematic review also examined the role of social determinants in the amplification and mitigation of chronic pain in children and adolescents. Findings suggest that the social environment exerts a profound influence on the individual’s experience of chronic pain, consistent with the biopsychosocial framework. This model conceptualizes chronic pain as not only biological but also socially shaped, involving variables, like family dynamics, school pressures, friendships, and economic context. The family unit, as a primary social structure, plays a pivotal role in both the development and management of chronic pain in children. This perspective is supported by several studies [23-27], indicating that overprotective or neglectful parenting is tied to more severe pain and poorer adaptability in children [23–26]. These parenting behaviors may reinforce helplessness and dependency, thereby obstructing the development of effective coping strategies. Additionally, parental psychological distress or a history of chronic pain may indirectly exacerbate pain intensity in children by instilling negative pain-related expectations and fostering maladaptive coping responses [23, 24, 26, 27].

The educational environment also constitutes a critical social domain. School disengagement, poor attendance, and unsafe academic settings have all been associated with increased rates of pediatric chronic pain [19, 21, 36]. Likewise, problematic peer dynamics can act as stress triggers, intensifying both pain symptoms and emotional distress in young individuals [23, 31, 56].

Socioeconomic status also exerts a significant influence on chronic pain experiences. Evidence indicates that children living in underprivileged households marked by parental joblessness or low income are more likely to suffer from frequent and intense chronic pain episodes [19, 29, 21]. Mechanisms such as persistent stress, limited access to medical care, and weaker coping skills may explain this socioeconomic link to chronic pain [57, 58]. While socioeconomic status may not directly dictate pain severity, it can shape outcomes by affecting healthcare access and treatment equity [59].

Finally, findings highlight the biological underpinnings of chronic pain, including gender disparities, dysfunctions in endogenous pain inhibition systems, neuroplasticity modifications, neural maturation, obesity-related systemic inflammation, and genetic/epigenetic influences.

One of the most notable biological observations is the elevated risk of chronic pain in girls aged 16–18, with prevalence reaching 76% according to cited studies. Possible explanations for this gender difference include hormonal variability, neural distinctions, and multifactorial biopsychosocial influences [20, 28]. Overall, these insights underscore the need for developmentally tailored biopsychosocial treatment approaches to effectively address chronic pain in children and adolescents.

Conclusion

Chronic pain in children and adolescents is a complex, multifaceted phenomenon shaped by the intricate interplay of biological, psychological, and social determinants. Genetic predispositions, female sex, dysfunction in endogenous pain-inhibitory systems, obesity-related systemic inflammation, alterations in the mesolimbic dopaminergic circuitry, neuroplasticity changes, as well as advancing age and neural maturation may heighten pain sensitivity. At the same time, psychological components, such as emotional distress, catastrophic thinking, difficulties in regulating emotions, levels of resilience, and availability of multidisciplinary interventions, strongly shape both how pain is perceived and how well individuals function.

In addition to personal traits, the social context, including problematic family environments, school-related obstacles, peer interactions, and economic background, plays a crucial role in shaping how children and adolescents experience chronic pain. Findings from this systematic review emphasize the biopsychosocial model as a pivotal framework in understanding chronic pain etiology.

Collectively, the findings underscore the necessity of creating age-appropriate, integrated biopsychosocial approaches that respond comprehensively to the specific needs of children and adolescents. It is essential that future research emphasize long-term and interventional designs to clarify causal relationships and evaluate the effectiveness of evidence-based, multidisciplinary treatments grounded in the biopsychosocial perspective.

Study limitations

Many of the included studies employed cross-sectional designs, which restrict conclusions about causality. There was heterogeneity in measurement tools and definitions across studies, making synthesis and comparison more complex. Additionally, only English-language, peer-reviewed studies were included. This review has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings, potentially introducing language and publication bias. Although study-level risk of bias was assessed using a standardized checklist, bias at the outcome level was not consistently evaluated. Moreover, the exclusion of grey literature and unpublished data might have limited the comprehensiveness of the review.

To overcome these limitations, future studies are recommended to adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to explore causal relationships between biopsychosocial factors and chronic pain. The development of culturally relevant frameworks tailored to non-Western populations and the use of standardized international tools can enhance the comparability of studies. Additionally, integrating physiological data (such as inflammatory markers) with psychosocial factors and focusing on specific subgroups (e.g. adolescents with comorbid disorders) may provide a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms and support the design of personalized interventions. These approaches could pave the way for the development of more comprehensive strategies in managing chronic pain in children and adolescents.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is a systematic review with no human or animal sample.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all individuals whose contributions to literature search and technical guidance supported the development of this review.

References

- Roman-Juan J, Sánchez-Rodríguez E, Solé E, Castarlenas E, Jensen MP, Miró J. Psychological factors and pain medication use in adolescents with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2023; 24(10):1183-8. [ [DOI:10.1093/pm/pnad075] [PMID]

- Lo Cascio A, Cascino M, Dabbene M, Paladini A, Viswanath O, Varrassi G, Latina R. Epidemiology of Pediatric Chronic Pain: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2025; 29(1):71. [DOI:10.1007/s11916-025-01380-5] [PMID]

- Rau LM, Grothus S, Sommer A, Grochowska K, Claus BB, Zernikow B, et al. Chronic pain in schoolchildren and its association with psychological wellbeing before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Health. 2021; 69(5):721-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.027] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Beynon AM, Hebert JJ, Hodgetts CJ, Boulos LM, Walker BF. Chronic physical illnesses, mental health disorders, and psychological features as potential risk factors for back pain from childhood to young adulthood: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur Spine J. 2020; 29(3):480-96. [DOI:10.1007/s00586-019-06278-6] [PMID]

- Miró J, Roman-Juan J, Sánchez-Rodríguez E, Solé E, Castarlenas E, Jensen MP. Chronic pain and high impact chronic pain in children and adolescents: A cross-sectional study. J Pain. 2023; 24(5):812-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpain.2022.12.007] [PMID]

- Faltyn M, Cresswell L, Van Lieshout RJ. Psychological problems in parents of children and adolescents with chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Health Med. 2021; 26(3):298-312. [DOI:10.1080/13548506.2020.1778756] [PMID]

- Tutelman PR, Langley CL, Chambers CT, Parker JA, Finley GA, Chapman D, et al. Epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents: A protocol for a systematic review update. BMJ open. 2021; 11(2):e043675. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043675]

- Yong RJ, Mullins PM, Bhattacharyya N. Prevalence of chronic pain among adults in the United States. Pain. 2022; 163(2):e328-32. [DOI:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002291] [PMID]

- Rogers AH, Farris SG. A meta-analysis of the associations of elements of the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain with negative affect, depression, anxiety, pain-related disability and pain intensity. Eur J Pain. 2022; 26(8):1611-35. [DOI:10.1002/ejp.1994] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Murray CB, de la Vega R, Murphy LK, Kashikar-Zuck S, Palermo TM. The prevalence of chronic pain in young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2022; 163(9):e972-84. [DOI:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002541] [PMID]

- Essner BS, Tran ST, Koven ML. Biopsychosocial approaches to pediatric chronic pain management. In: Shah RD, Suresh S, editors. Opioid therapy in infants, children, and adolescents. New York: Springer; 2020. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-36287-4_16]

- Zhang D, Lee EKP, Mak ECW, Ho CY, Wong SYS. Mindfulness-based interventions: An overall review. Br Med Bull. 2021; 138(1):41-57. [DOI:10.1093/bmb/ldab005] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rosky CJ, Roberts RL, Hanley AW, Garland EL. Mindful lawyering: A pilot study on mindfulness training for law students. Mindfulness. 2022; 13(9):2347-56. [DOI:10.1007/s12671-022-01965-w] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Schulte-Goecking H, Azqueta-Gavaldon M, Storz C, Woiczinski M, Fraenkel P, Leukert J, et al. Psychological, social and biological correlates of body perception disturbance in complex regional pain syndrome. Curr Psychol. 2022; 41(3):1337-47. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-020-00635-1]

- Brintz CE, Roth I, Faurot K, Rao S, Gaylord SA. Feasibility and acceptability of an abbreviated, four-week mindfulness program for chronic pain management. Pain Med. 2020; 21(11):2799-810. [DOI:10.1093/pm/pnaa208] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Martí L, Garriga-Cazorla H, Roman-Juan J, Miró J. Family-related factors in children and adolescents with chronic pain: A systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2025; 29(6):e70038. [DOI:10.1002/ejp.70038] [PMID]

- Koechlin H, Locher C, Prchal A. Talking to children and families about chronic pain: The importance of pain education-an introduction for pediatricians and other health care providers. Children. 2020; 7(10):179. [DOI:10.3390/children7100179] [PMID] [PMCID]

- O'Connor S, Mayne A, Hood B. Virtual reality-based mindfulness for chronic pain management: A scoping review. Pain Manag Nurs. 2022; 23(3):359-69. [DOI:10.1016/j.pmn.2022.03.013] [PMID]

- Chen Y, Liu Z, Werneck AO, Huang T, Van Damme T, Kramer AF, et al. Social determinants of health and youth chronic pain. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2024; 57:101911. [DOI:10.1016/j.ctcp.2024.101911] [PMID]

- Pavlova M, Noel M, Orr SL, Walker A, Madigan S, McDonald SW, et al. Early childhood risk factors for later onset of pediatric chronic pain: A multi-method longitudinal study. BMC Pediatr. 2024; 24(1):508. [DOI:10.1186/s12887-024-04951-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Vandeleur DM, Cunningham MM, Palermo TM, Groenewald CB. Association of neighborhood characteristics and chronic pain in children and adolescents in the United States. Clin J Pain. 2024; 40(3):174-81. [DOI:10.1097/AJP.0000000000001179] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Wolock ER, Sinisterra M, Fedele DA, Bishop MD, Boissoneault J, Janicke DM. A systematic review of social functioning and peer relationships in adolescents with chronic pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2025; 50(4):354-76. [DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/jsaf014]

- Ross AC, Simons LE, Feinstein AB, Yoon IA, Bhandari RP. Social risk and resilience factors in adolescent chronic pain: Examining the role of parents and peers. J Pediatr Psychol. 2018; 43(3):303-13. [DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/jsx118] [PMID]

- Palermo TM, Valrie CR, Karlson CW. Family and parent influences on pediatric chronic pain: A developmental perspective. Am Psychol. 2014; 69(2):142-52. [DOI:10.1037/a0035216] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lewandowski AS, Palermo TM, Stinson J, Handley S, Chambers CT. Systematic review of family functioning in families of children and adolescents with chronic pain. J Pain. 2010; 11(11):1027-38. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpain.2010.04.005] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Donnelly TJ, Palermo TM, Newton-John TRO. Parent cognitive, behavioural, and affective factors and their relation to child pain and functioning in pediatric chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2020; 161(7):1401-19. [DOI:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001833] [PMID]

- Poppert Cordts KM, Stone AL, Beveridge JK, Wilson AC, Noel M. The (parental) whole is greater than the sum of its parts: A multifactorial model of parent factors in pediatric chronic pain. J Pain. 2019; 20(7):786-95. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpain.2019.01.004] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Haraldstad K, Christophersen KA, Helseth S. Health-related quality of life and pain in children and adolescents: A school survey. BMC Pediatr. 2017; 17(1):174. [DOI:10.1186/s12887-017-0927-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Groenewald CB, Murray CB, Palermo TM. Adverse childhood experiences and chronic pain among children and adolescents in the United States. Pain Rep. 2020; 5(5):e839. [DOI:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000839] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Calvo-Muñoz I, Gómez-Conesa A, Sánchez-Meca J. Physical therapy treatments for low back pain in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013; 14:55. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2474-14-55] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Forgeron PA, King S, Stinson JN, McGrath PJ, MacDonald AJ, Chambers CT. Social functioning and peer relationships in children and adolescents with chronic pain: A systematic review. Pain Res Manag. 2010; 15(1):27-41. [DOI:10.1155/2010/820407] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Tran ST, Jastrowski Mano KE, Anderson Khan K, Davies WH, Hainsworth KR. Patterns of anxiety symptoms in pediatric chronic pain as reported by youth, mothers, and fathers. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology. 2016; 4(1):51-62.[DOI: 10.1037/cpp000012

- Simons LE. Fear of pain in children and adolescents with neuropathic pain and complex regional pain syndrome. Pain. 2016; 157:S90-7. [DOI:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000377] [PMID]

- Stahlschmidt L, Rosenkranz F, Dobe M, Wager J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents with chronic pain. Health Psychol. 2020; 39(5):463-70. [DOI:10.1037/hea0000859] [PMID]

- Miller MM, Scott EL, Trost Z, Hirsh AT. Perceived injustice is associated with pain and functional outcomes in children and adolescents with chronic pain: A preliminary examination. J Pain. 2016; 17(11):1217-26. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpain.2016.08.002] [PMID]

- Wager J, Brown D, Kupitz A, Rosenthal N, Zernikow B. Prevalence and associated psychosocial and health factors of chronic pain in adolescents: Differences by sex and age. Eur J Pain. 2020; 24(4):761-72. [DOI: 10.1002/ejp.1526] [PMID]

- Simons LE, Sieberg CB, Claar RL. Anxiety and impairment in a large sample of children and adolescents with chronic pain. Pain Res Manag. 2012; 17(2):93-7. [DOI:10.1155/2012/420676] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mei Q, Li C, Yin Y, Wang Q, Wang Q, Deng G. The relationship between the psychological stress of adolescents in school and the prevalence of chronic low back pain: A cross-sectional study in China. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2019; 13:24. [DOI:10.1186/s13034-019-0283-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Pascali M, Matera E, Craig F, Torre F, Giordano P, Margari F, et al. Cognitive, emotional, and behavioral profile in children and adolescents with chronic pain associated with rheumatic diseases: A case-control study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019; 24(3):433-45. [DOI:10.1177/1359104518805800] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fisher E, Law E, Dudeney J, Palermo TM, Stewart G, Eccleston C. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; 9(9):CD003968. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD003968.pub5] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Knook LM, Konijnenberg AY, van der Hoeven J, Kimpen JL, Buitelaar JK, van Engeland H, et al. Psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents presenting with unexplained chronic pain: What is the prevalence and clinical relevancy? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011; 20(1):39-48. [DOI:10.1007/s00787-010-0146-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Noel M, Groenewald CB, Beals-Erickson SE, Gebert JT, Palermo TM. Chronic pain in adolescence and internalizing mental health disorders: A nationally representative study. Pain. 2016; 157(6):1333-8. [DOI:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000522] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Tegethoff M, Belardi A, Stalujanis E, Meinlschmidt G. Comorbidity of mental disorders and chronic pain: Chronology of onset in adolescents of a national representative cohort. J Pain. 2015; 16(10):1054-64. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpain.2015.06.009] [PMID]

- Cousins LA, Kalapurakkel S, Cohen LL, Simons LE. Topical review: Resilience resources and mechanisms in pediatric chronic pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015; 40(9):840-5. [DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/jsv037] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Young MA, Anang P, Gavalova A. Pediatric chronic pain, resilience and psychiatric comorbidity in Canada: A retrospective, comparative analysis. Front Health Serv. 2022; 2:852322. [DOI:10.3389/frhs.2022.852322] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Koechlin H, Coakley R, Schechter N, Werner C, Kossowsky J. The role of emotion regulation in chronic pain: A systematic literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2018; 107:38-45. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.02.002] [PMID]

- Caes L, Dick B, Duncan C, Allan J. The cyclical relation between chronic pain, executive functioning, emotional regulation, and self-management. J Pediatr Psychol. 2021; 46(3):286-92. [DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa114] [PMID]

- Griggs S, Walker RK. The role of hope for adolescents with a chronic illness: An integrative review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016; 31(4):404-21. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2016.02.011] [PMID]

- Champion D, Bui M, Bott A, Donnelly T, Goh S, Chapman C, et al. Familial and genetic influences on the common pediatric primary pain disorders: A twin family study. Children. 2021; 8(2):89. [DOI:10.3390/children8020089] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hainsworth KR, Simpson PM, Raff H, Grayson MH, Zhang L, Weisman SJ. Circulating inflammatory biomarkers in adolescents: Evidence of interactions between chronic pain and obesity. Pain Rep. 2021; 6(1):e916. [DOI:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000916] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Vinall J, Pavlova M, Asmundson GJ, Rasic N, Noel M. Mental health comorbidities in pediatric chronic pain: A narrative review of epidemiology, models, neurobiological mechanisms and treatment. Children. 2016; 3(4):40. [DOI:10.3390/children3040040] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Serafini RA, Pryce KD, Zachariou V. The mesolimbic dopamine system in chronic pain and associated affective comorbidities. Biol Psychiatry. 2020; 87(1):64-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.10.018] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Liossi C, Laycock H, Radhakrishnan K, Hussain Z, Schoth DE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of conditioned pain modulation in children and young people with chronic pain. Children. 2024; 11(11):1367. [DOI:10.3390/children11111367] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lepping RJ, Hoffart CM, Bruce AS, Taylor JM, Mardis NJ, Lim SL, et al. Pediatric neural changes to physical and emotional pain after intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment: A pilot study. Clin J Pain. 2024; 40(11):665-72. [DOI:10.1097/AJP.0000000000001237] [PMID]

- Boerner KE, Eccleston C, Chambers CT, Keogh E. Sex differences in the efficacy of psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2017; 258(4):569-82. [DOI:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000803] [PMID]

- Macedo RB, Coelho-e-Silva MJ, Sousa NF, Valente-dos-Santos J, Machado-Rodrigues AM, Cumming SP, et al. Quality of life, school backpack weight, and nonspecific low back pain in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2015; 91(3):263-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpedp.2015.03.001]

- Lau JYF, Heathcote LC, Beale S, Gray S, Jacobs K, Wilkinson N, et al. Cognitive biases in children and adolescents with chronic pain: A review of findings and a call for developmental research. J Pain. 2018; 19(6):589-98. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpain.2018.01.005] [PMID]

- Page MJ, Moher D, McKenzie JE. Introduction to preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses 2020 and implications for research synthesis methodologists. Res Synth Methods. 2022; 13(2):156-63. [DOI:10.1002/jrsm.1535] [PMID]

- Gong C, Shan H, Sun Y, Zheng J, Zhu C, Zhong W, et al. Social support as a key factor in chronic pain management programs: A scoping review. Curr Psychol. 2024; 43(31):25453-67. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-024-06233-9]

Type of Study: Systematic Review |

Subject:

Pediatric Psychology

Received: 2025/05/5 | Accepted: 2025/06/28 | Published: 2025/07/19

Received: 2025/05/5 | Accepted: 2025/06/28 | Published: 2025/07/19

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |