Volume 13, Issue 4 (10-2025)

J. Pediatr. Rev 2025, 13(4): 339-344 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

MZ J, Umapathy N, Mahesh M, Gulab Chaudhary D. Diagnostic Accuracy of Pulse Oximetry in Children With Different Skin Tones: A Cross-sectional Study. J. Pediatr. Rev 2025; 13 (4) :339-344

URL: http://jpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-783-en.html

URL: http://jpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-783-en.html

Diagnostic Accuracy of Pulse Oximetry in Children With Different Skin Tones: A Cross-sectional Study

1- Department of Paediatrics, Postgraduate, Saveetha University (SIMATS), Chennai, India.

2- Department of Paediatrics, Postgraduate, Saveetha University (SIMATS), Chennai, India. ,navinu02@gmail.com

2- Department of Paediatrics, Postgraduate, Saveetha University (SIMATS), Chennai, India. ,

Keywords: Pulse oximetry, Diagnostic accuracy, Skin tone, Fitzpatrick scale, Pediatric hypoxemia, Oxygen saturation (SaO₂), Arterial blood gas (ABG)

Full-Text [PDF 352 kb]

(177 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (245 Views)

Full-Text: (58 Views)

Introduction

Pulse oximetry is a cornerstone of non-invasive monitoring in pediatric medicine, offering real-time estimation of arterial oxygen saturation (peripheral oxygen saturation [SpO₂]) and is widely used in emergency, operative, and intensive care settings due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and clinical utility [1–3]. Its role is particularly vital in low-resource environments where arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis may not be readily accessible. However, emerging evidence has raised concerns about the accuracy of SpO₂ readings across different skin tones. Pulse oximeters, which rely on differential light absorption, may be affected by melanin content, leading to systematic overestimation of SpO₂ in individuals with darker skin tones [1, 3]. This measurement bias has been well-documented in adult populations, but pediatric-specific data remain sparse.

Although some pediatric studies report similar trends, such as a mean SpO₂–SaO₂ difference of 2.58 in Black children versus 0.89 in White children, the use of race or ethnicity as a proxy for skin tone has been a major limitation [3–5]. Most available studies have indicated that overestimation is more pronounced at lower saturations; yet, few have used validated skin tone assessment tools [1, 5]. This lack of objective, reproducible skin tone assessment limits the generalizability and precision of findings. The need for prospective studies using validated tools such as the Fitzpatrick Skin Type classification is widely recognized. To address this gap, the present study prospectively evaluates the diagnostic accuracy of pulse oximetry (SpO₂) in children stratified by objectively classified skin tone using the Fitzpatrick skin type scale. By comparing SpO₂ with ABG-derived SaO₂, we aimed to quantify the measurement bias across skin tones and assess its clinical implications. We hypothesized that darker skin tones are associated with significantly greater overestimation of SpO₂, raising concerns about potential under-recognition of hypoxemia in this group.

Methods

Study design and participants

This observational, cross-sectional study was conducted on nearly 300 children over a 6-month period (January-June 2025) admitted to the pediatric ward of the hospital affiliated to Saveetha Medical College in India for various illnesses. The sample size was calculated as 71 per group using the Equation 1:

1. n=(Z1-α2+Z1-β)2×σ2/Δ2,

considering a two-sided α=0.05 (Z1-α2=1.96), 80% power (Z1-β=0.84), an expected mean difference (Δ) of 2% between ABG and SpO, and a standard deviation (σ) of 6% derived from pilot data. Thus, a minimum of 213 participants (three skin tone groups) was required. Considering a 20–25% sample dropout, the sample size increased to 270.

Of 376 children assessed for eligibility, 300 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis (100 per three groups). This ensured adequate power for statistical comparisons. The participants were selected using a consecutive sampling method. Children who required ABG analysis and those with parental consent were included. Children with hemodynamic instability requiring vasoactive support (dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine), those with poor peripheral perfusion (capillary refill time >2 seconds with cold peripheries in a thermoneutral environment), and those requiring intensive care support were excluded.

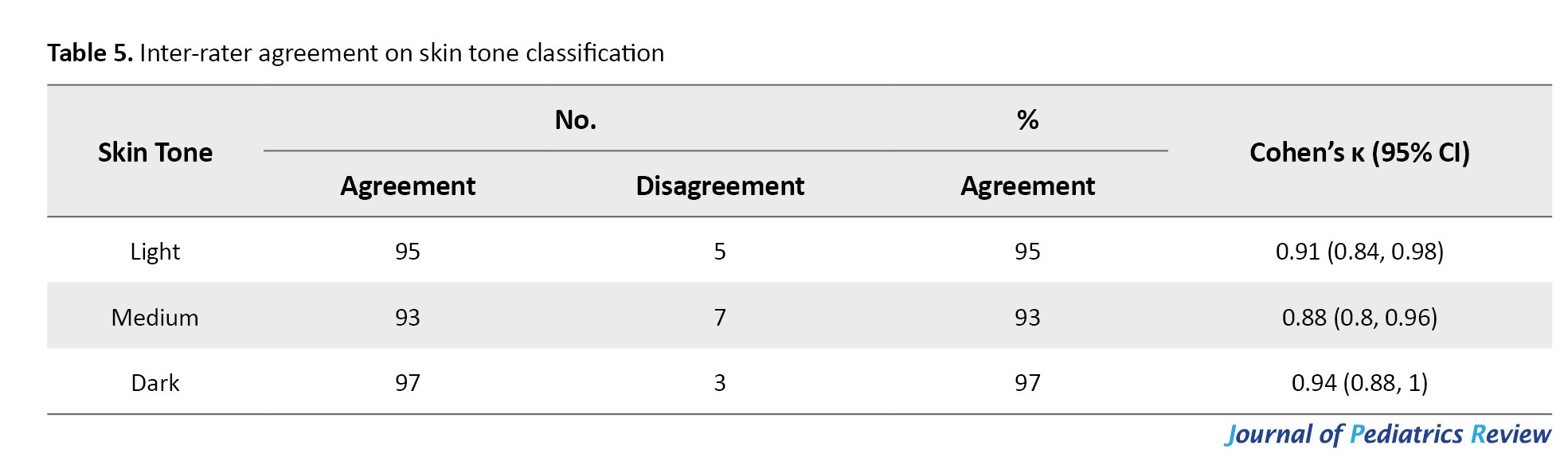

Skin tone was assessed using the Fitzpatrick skin type scale (type I to VI), based on visual inspection by trained clinical staff blinded to oximetry readings. For analysis, skin tones were grouped into three categories: Light (type I–II), medium (type III–IV), dark (type V–VI). A second independent rater assessed inter-rater agreement for the allocation of patients using Cohen’s kappa (κ).

Data collection

We obtained simultaneous SpO₂ and ABG-derived SpO₂ readings. SpO₂ measurements were done using a standardized, FDA-approved pulse oximeter (model XYZ) with an appropriate sensor size for age and weight. SaO₂ was measured via co-oximetry from an arterial blood sample collected for clinical purposes. All SpO₂ measurements were recorded within 5 minutes of ABG sampling under stable respiratory and hemodynamic conditions. Other collected data included: Age, sex, weight, and underlying diagnosis; site of pulse oximeter probe placement, and room air vs supplemental oxygen status.

The primary outcome was the mean difference between SpO₂ and SaO₂, categorized by skin tone type. Secondary outcomes included: Proportion of readings with clinically significant overestimation (SpO₂≥92% when SaO₂<88%) and the root mean square error (RMSE) of SpO₂ compared to SaO₂.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present demographic and clinical characteristics. Agreement between SpO₂ and SaO₂ was assessed using Bland–Altman plots and mean difference at a 95% confidence interval (CI). ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare differences among skin tone groups. Multivariable linear regression was performed to control for potential confounders (e.g. age, oxygen use, site of measurement). Statistical significance was set at 0.05. Analyses were performed in SPSS software, version 27 and R software, version 4.2.2.

Results

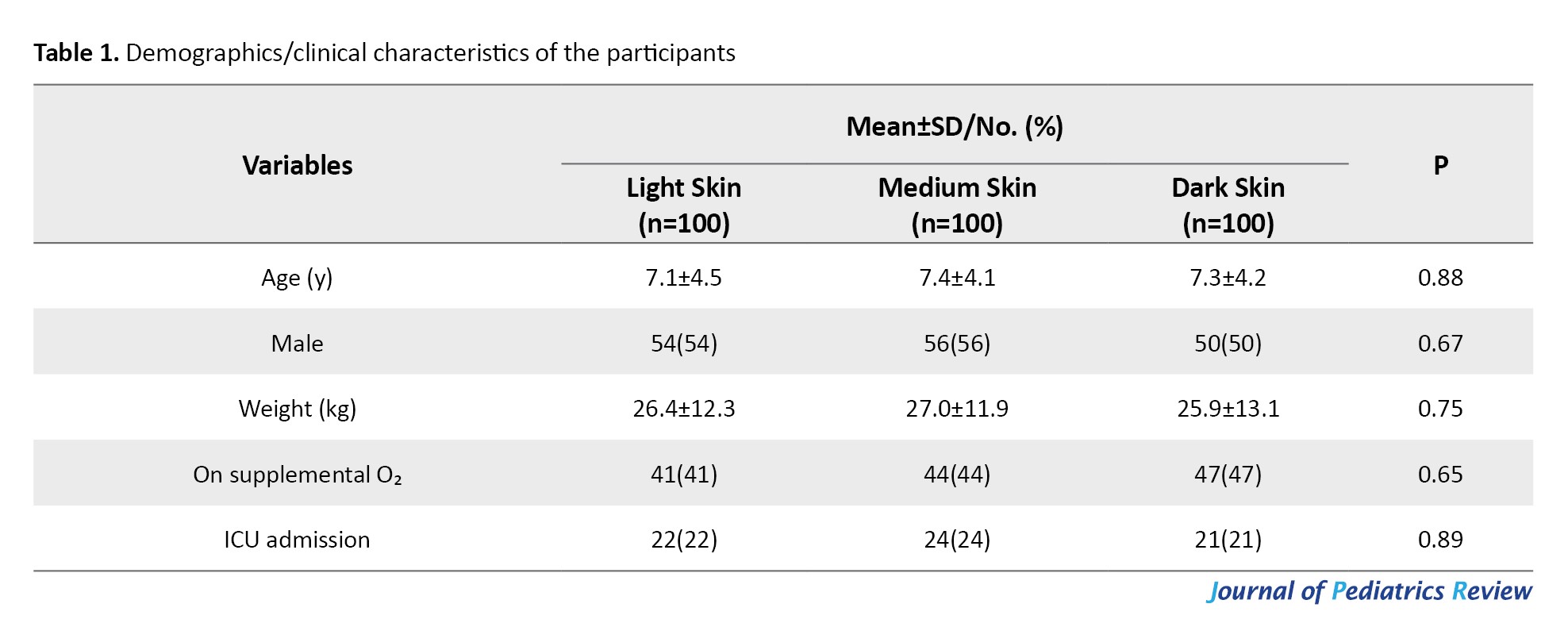

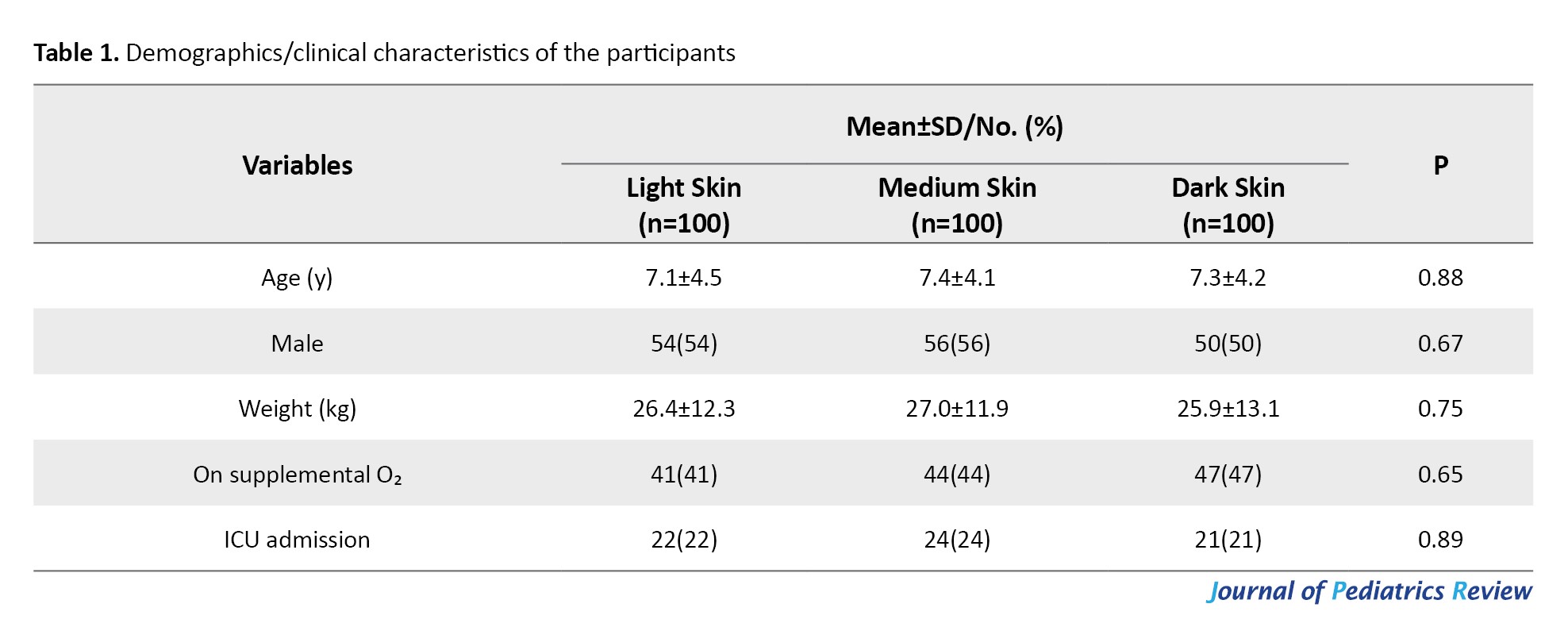

Table 1 presents the demographic/clinical characteristics of the participants.

There were no significant differences in demographic/clinical characteristics among the three skin tone groups (P>0.05). Therefore, age, weight, and sex distribution, oxygen supplementation, and ICU admission rates were similar among light-, medium-, and dark-skinned children at baseline.

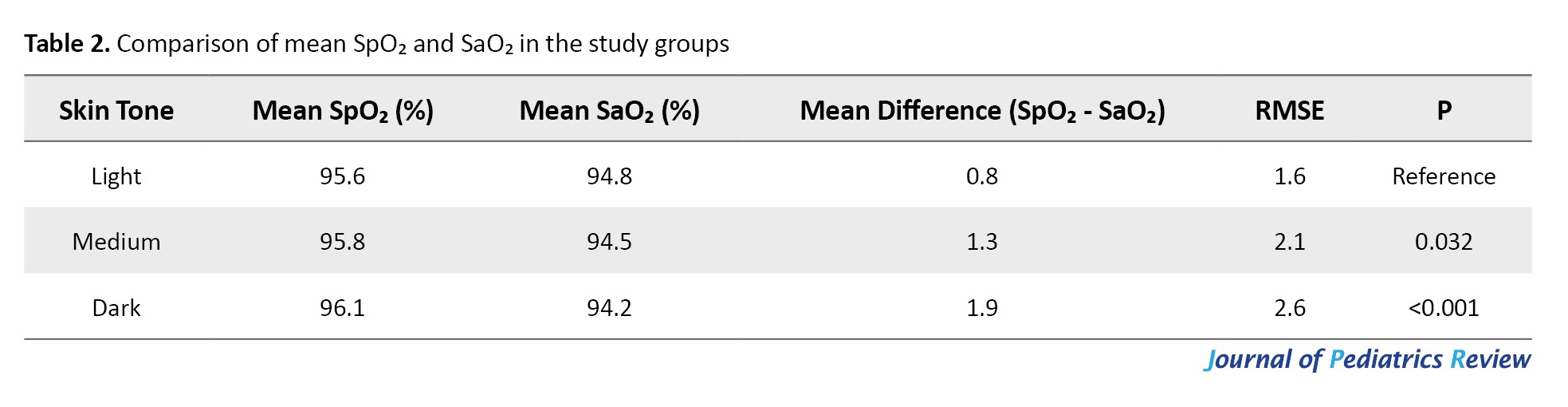

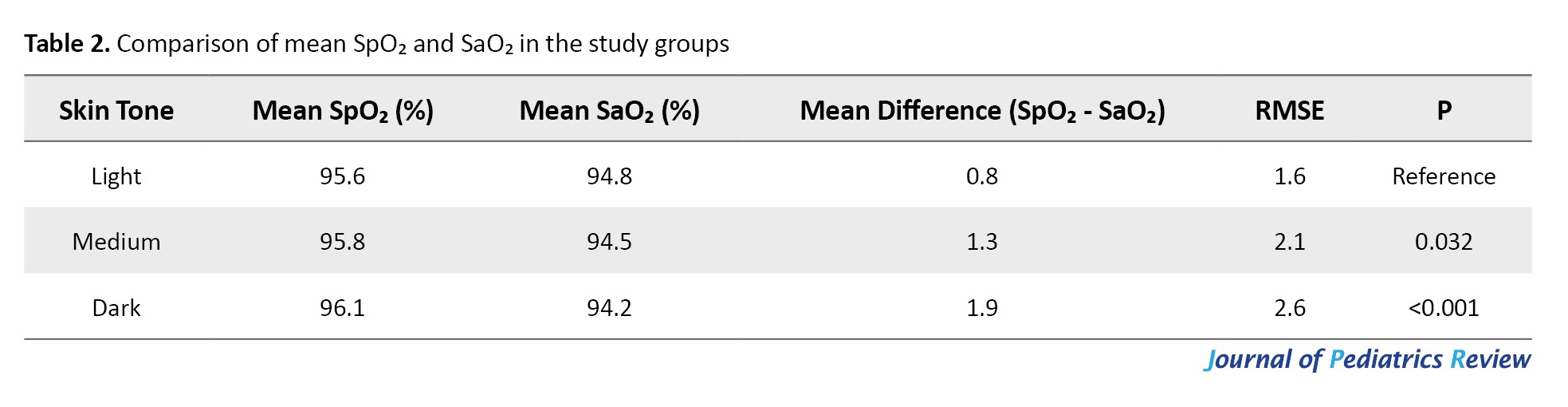

According to the results in Table 2, pulse oximetry (SpO₂) overestimated SaO₂ in all groups, with a significant bias observed in the dark-skinned group (P<0.001).

Children with dark skin had a mean bias of +1.9%, higher than that of light-skinned children (+0.8%). The RMSE was also higher in the dark-skinned group, indicating reduced measurement accuracy. These findings suggest a discrepancy in SpO₂ readings related to skin tone.

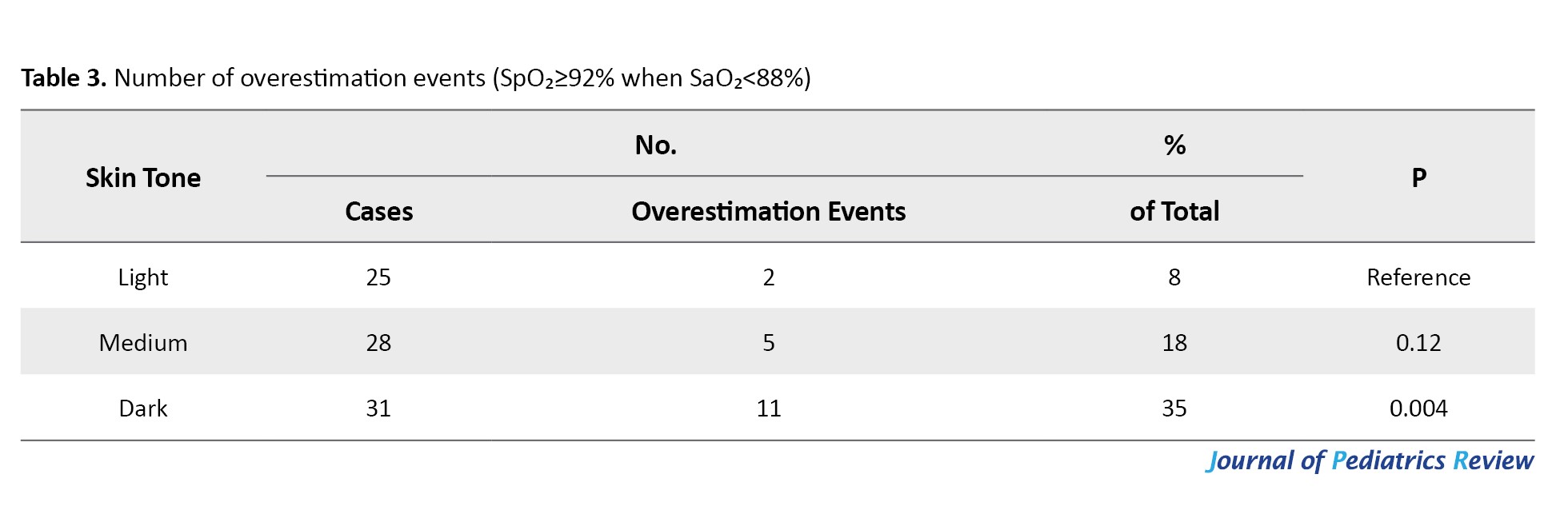

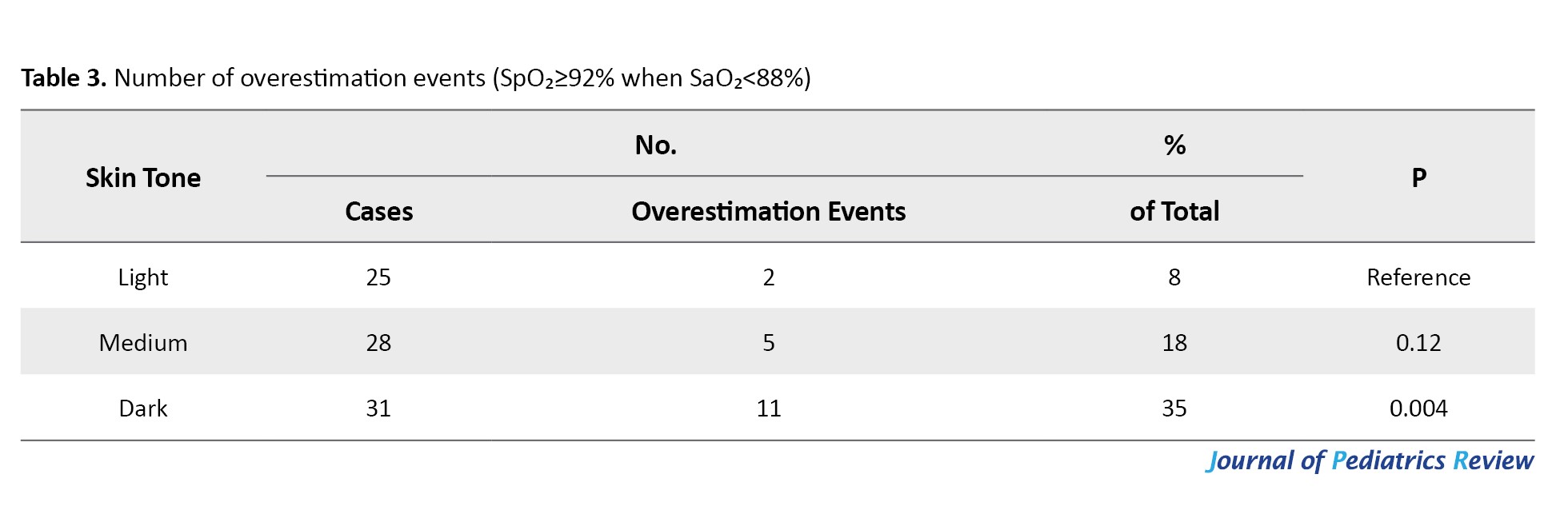

According to the results in Table 3, among children with SaO₂<88%, overestimation by pulse oximetry (SpO₂≥92%) occurred more frequently in the dark-skinned group (35%) compared to the medium-skinned (18%) and light-skinned (8%) groups.

The difference in overestimation was statistically significant in the dark-skinned group (P=0.004), highlighting a potential clinical safety concern in darker-skinned children, who may be falsely reassured by normal pulse oximeter readings.

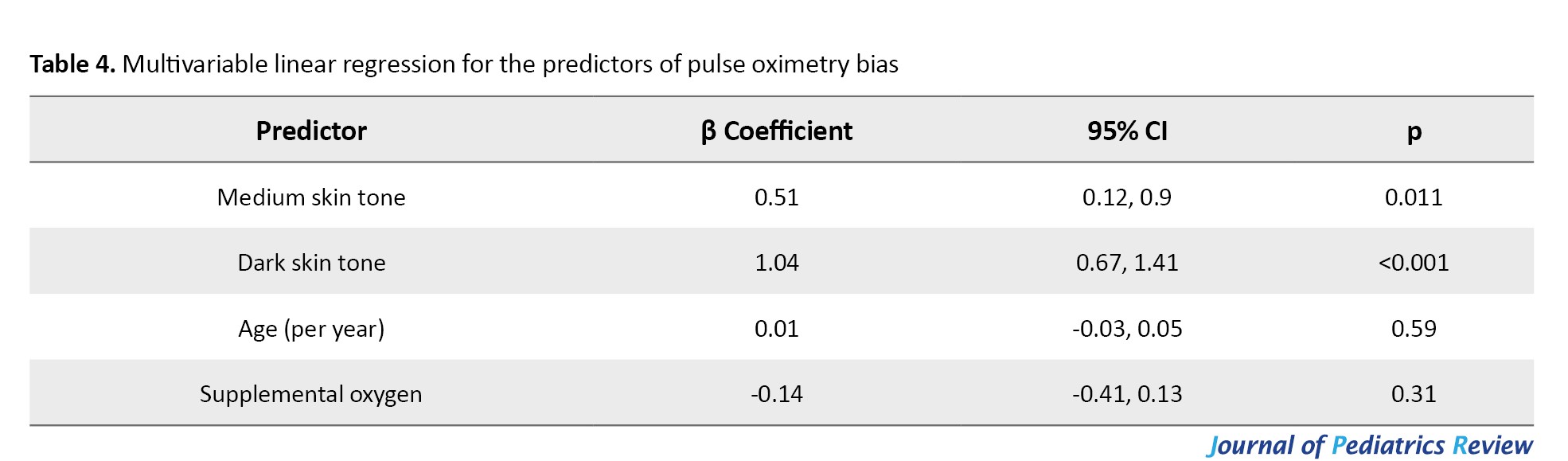

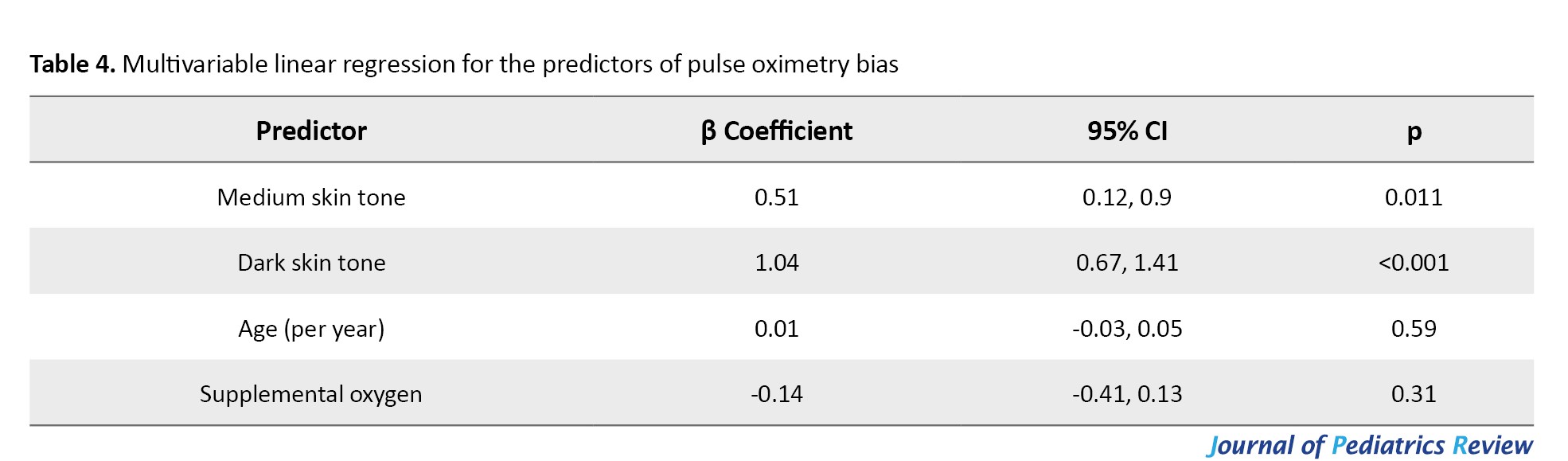

Multivariable regression analysis (Table 4) showed that dark skin tone (P<0.001) and medium skin tone (P=0.011) were significantly associated with greater pulse oximetry bias.

The dark skin tone increases the bias by 1.04 units, and the medium skin tone increases it by 0.51 units. Age and oxygen supplementation were not significant predictors of pulse oximetry bias (P>0.05).

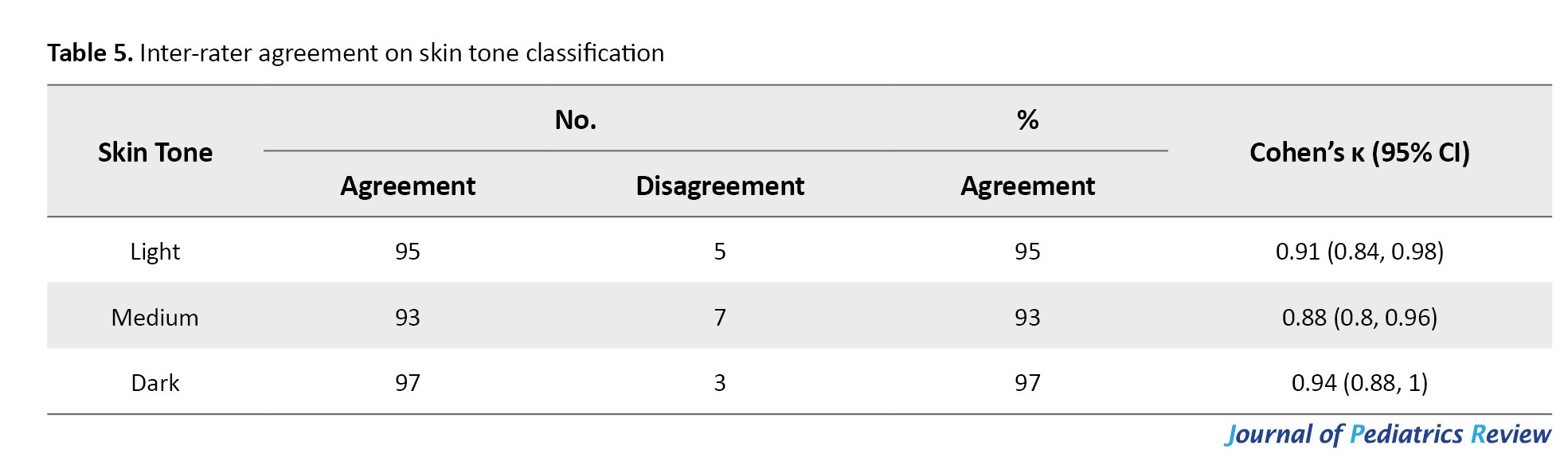

There was high inter-rater agreement in skin tone classification using the Fitzpatrick scale, with overall agreement exceeding 90% in all categories (κ=0.91 for light, 0.88 for medium, and 0.94 for dark skin tones) (Table 5).

These results support the reliability of visual skin tone classification in our study.

Discussion

This prospective study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of pulse oximetry in the pediatric population stratified by objectively classified skin tone using the Fitzpatrick scale. The findings demonstrated a statistically significant overestimation of arterial SpO₂ by pulse oximetry (SpO₂). The magnitude of this bias was significantly higher in dark-skinned children. For these children, there was a mean SpO₂–SaO₂ bias of +1.9%, compared to +0.8% in light-skinned children. The RMSE was also high, indicating reduced measurement precision in dark skin tones. Among children with true hypoxemia (SaO₂<88%), falsely high SpO₂ readings (≥92%) occurred in 35% of dark-skinned children, compared to only 8% in those with light skin. This discrepancy persisted even after adjustment for age and oxygen supplementation, underscoring skin tone as an independent predictor of pulse oximetry bias.

Our findings align with a growing body of evidence indicating skin tone–related discrepancies in pulse oximeter readings. Adult ICU studies have reported similar patterns, with darker-skinned patients exhibiting a mean bias of 1.05% and an accuracy RMSE of 4.15%, compared to 0.34% in lighter-skinned counterparts [6]. In children, a study identified SpO₂–SaO₂ differences of 2.58% in black children versus 0.89% in white children during cardiac procedures [2], consistent with the magnitude of bias found in our study. Moreover, pediatric prospective studies have confirmed the presence of occult hypoxemia, defined as SaO₂<88% despite SpO₂≥92%, in up to 7% of children with darker skin versus 0% in lighter skin groups [7]. A meta-analysis further supported these concerns, reporting a pooled SpO₂ overestimation bias of 1.11% in individuals with darker skin, particularly at SpO₂ below 90% [8]. Our study contributes to pediatric-specific prospective research, addressing a critical knowledge gap by utilizing standardized skin tone classification.

Unlike previous studies that relied on self-reported race or ethnicity as proxies for skin tone, we utilized the Fitzpatrick scale, a validated and reproducible tool for skin type classification. This approach enhances the objectivity and clinical relevance of our findings. Other novel methods such as the Monk skin tone scale and spectrophotometric techniques, have recently been explored for more granular pigmentation assessment [9]. A high inter-rater agreement (κ>0.88) in our study confirmed that visual classification of skin tones remains a practical and reliable method in clinical settings. Discrepancies between race-based and skin tone-based measures have been emphasized in recent frameworks calling for more standardized, multi-dimensional approaches to skin tone assessment [9, 10].

Our findings are consistent with data from the POSTer-Child study, which reported a SpO₂–SaO₂ bias of 3.67% in dark-skinned children compared to 1.37% in light-skinned peers, with occult hypoxemia occurring in 8.3% of the former group [11]. These discrepancies are clinically significant, particularly in settings where SpO₂ thresholds are used for triaging or initiating oxygen therapy. Several studies have also questioned the World Health Organization (WHO)’s current cutoff of SpO₂<90% for initiating oxygen in children with respiratory illness, noting that adverse outcomes have been observed even within the 90–92% range [2].

The overestimation of SpO₂ in darker-skinned children is not a benign artifact but a clinically significant diagnostic gap. Exclusive reliance on pulse oximetry may lead to delayed recognition of hypoxemia, particularly in settings where access to ABG analysis or continuous clinical reassessment is limited. Our findings underscore the need for heightened clinical vigilance when interpreting pulse oximetry in children with darker skin tones; improved calibration algorithms for pulse oximeters that account for melanin levels during design and validation; and incorporation of confirmatory measures (e.g. ABG, capnography, or clinical scoring) in decision-making when readings are borderline or discordant with clinical signs.

This study had several strengths including a prospective design, standardized simultaneous collection of SpO₂ and SaO₂ measurements, and the use of a validated, reproducible skin tone scale with excellent inter-rater reliability. Adjustment for clinical covariates enhances internal validity. However, there were some limitations. The single-center design may limit external generalizability. The Fitzpatrick scale, although standardized, is based on visual assessment and may be influenced by factors such as lighting or the observer's perception. Exclusion of children with hemodynamic instability may reduce applicability to critically ill subgroups. Grouping skin tones into three broad categories, although pragmatic, does not capture the continuous gradations in pigmentation that newer tools aim to address [9, 10].

Conclusion

This study provides strong evidence that pulse oximetry overestimates arterial SpO₂ in children with darker skin tones, leading to a higher risk of undetected hypoxemia. These findings highlight an important disparity in pediatric monitoring, with implications for delayed recognition and treatment of hypoxic conditions in darker-skinned children. The use of an objective, validated skin tone classification method enhances the reliability of findings and emphasizes the need to move beyond race-based proxies in clinical research. Clinicians should be cautious when interpreting SpO₂ values in children with darker skin, particularly when readings appear borderline or inconsistent with clinical signs. This underscores the need for confirmatory testing or supplementary monitoring in critical care settings.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Saveetha Medical College, Chennai, India (Code: 014/12/2024/IEC/SMCH). Informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all children.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and supervision: Navin Umapathy; Investigation and writing: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Saveetha University for engaging them in research activity.

Pulse oximetry is a cornerstone of non-invasive monitoring in pediatric medicine, offering real-time estimation of arterial oxygen saturation (peripheral oxygen saturation [SpO₂]) and is widely used in emergency, operative, and intensive care settings due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and clinical utility [1–3]. Its role is particularly vital in low-resource environments where arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis may not be readily accessible. However, emerging evidence has raised concerns about the accuracy of SpO₂ readings across different skin tones. Pulse oximeters, which rely on differential light absorption, may be affected by melanin content, leading to systematic overestimation of SpO₂ in individuals with darker skin tones [1, 3]. This measurement bias has been well-documented in adult populations, but pediatric-specific data remain sparse.

Although some pediatric studies report similar trends, such as a mean SpO₂–SaO₂ difference of 2.58 in Black children versus 0.89 in White children, the use of race or ethnicity as a proxy for skin tone has been a major limitation [3–5]. Most available studies have indicated that overestimation is more pronounced at lower saturations; yet, few have used validated skin tone assessment tools [1, 5]. This lack of objective, reproducible skin tone assessment limits the generalizability and precision of findings. The need for prospective studies using validated tools such as the Fitzpatrick Skin Type classification is widely recognized. To address this gap, the present study prospectively evaluates the diagnostic accuracy of pulse oximetry (SpO₂) in children stratified by objectively classified skin tone using the Fitzpatrick skin type scale. By comparing SpO₂ with ABG-derived SaO₂, we aimed to quantify the measurement bias across skin tones and assess its clinical implications. We hypothesized that darker skin tones are associated with significantly greater overestimation of SpO₂, raising concerns about potential under-recognition of hypoxemia in this group.

Methods

Study design and participants

This observational, cross-sectional study was conducted on nearly 300 children over a 6-month period (January-June 2025) admitted to the pediatric ward of the hospital affiliated to Saveetha Medical College in India for various illnesses. The sample size was calculated as 71 per group using the Equation 1:

1. n=(Z1-α2+Z1-β)2×σ2/Δ2,

considering a two-sided α=0.05 (Z1-α2=1.96), 80% power (Z1-β=0.84), an expected mean difference (Δ) of 2% between ABG and SpO, and a standard deviation (σ) of 6% derived from pilot data. Thus, a minimum of 213 participants (three skin tone groups) was required. Considering a 20–25% sample dropout, the sample size increased to 270.

Of 376 children assessed for eligibility, 300 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis (100 per three groups). This ensured adequate power for statistical comparisons. The participants were selected using a consecutive sampling method. Children who required ABG analysis and those with parental consent were included. Children with hemodynamic instability requiring vasoactive support (dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine), those with poor peripheral perfusion (capillary refill time >2 seconds with cold peripheries in a thermoneutral environment), and those requiring intensive care support were excluded.

Skin tone was assessed using the Fitzpatrick skin type scale (type I to VI), based on visual inspection by trained clinical staff blinded to oximetry readings. For analysis, skin tones were grouped into three categories: Light (type I–II), medium (type III–IV), dark (type V–VI). A second independent rater assessed inter-rater agreement for the allocation of patients using Cohen’s kappa (κ).

Data collection

We obtained simultaneous SpO₂ and ABG-derived SpO₂ readings. SpO₂ measurements were done using a standardized, FDA-approved pulse oximeter (model XYZ) with an appropriate sensor size for age and weight. SaO₂ was measured via co-oximetry from an arterial blood sample collected for clinical purposes. All SpO₂ measurements were recorded within 5 minutes of ABG sampling under stable respiratory and hemodynamic conditions. Other collected data included: Age, sex, weight, and underlying diagnosis; site of pulse oximeter probe placement, and room air vs supplemental oxygen status.

The primary outcome was the mean difference between SpO₂ and SaO₂, categorized by skin tone type. Secondary outcomes included: Proportion of readings with clinically significant overestimation (SpO₂≥92% when SaO₂<88%) and the root mean square error (RMSE) of SpO₂ compared to SaO₂.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present demographic and clinical characteristics. Agreement between SpO₂ and SaO₂ was assessed using Bland–Altman plots and mean difference at a 95% confidence interval (CI). ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare differences among skin tone groups. Multivariable linear regression was performed to control for potential confounders (e.g. age, oxygen use, site of measurement). Statistical significance was set at 0.05. Analyses were performed in SPSS software, version 27 and R software, version 4.2.2.

Results

Table 1 presents the demographic/clinical characteristics of the participants.

There were no significant differences in demographic/clinical characteristics among the three skin tone groups (P>0.05). Therefore, age, weight, and sex distribution, oxygen supplementation, and ICU admission rates were similar among light-, medium-, and dark-skinned children at baseline.

According to the results in Table 2, pulse oximetry (SpO₂) overestimated SaO₂ in all groups, with a significant bias observed in the dark-skinned group (P<0.001).

Children with dark skin had a mean bias of +1.9%, higher than that of light-skinned children (+0.8%). The RMSE was also higher in the dark-skinned group, indicating reduced measurement accuracy. These findings suggest a discrepancy in SpO₂ readings related to skin tone.

According to the results in Table 3, among children with SaO₂<88%, overestimation by pulse oximetry (SpO₂≥92%) occurred more frequently in the dark-skinned group (35%) compared to the medium-skinned (18%) and light-skinned (8%) groups.

The difference in overestimation was statistically significant in the dark-skinned group (P=0.004), highlighting a potential clinical safety concern in darker-skinned children, who may be falsely reassured by normal pulse oximeter readings.

Multivariable regression analysis (Table 4) showed that dark skin tone (P<0.001) and medium skin tone (P=0.011) were significantly associated with greater pulse oximetry bias.

The dark skin tone increases the bias by 1.04 units, and the medium skin tone increases it by 0.51 units. Age and oxygen supplementation were not significant predictors of pulse oximetry bias (P>0.05).

There was high inter-rater agreement in skin tone classification using the Fitzpatrick scale, with overall agreement exceeding 90% in all categories (κ=0.91 for light, 0.88 for medium, and 0.94 for dark skin tones) (Table 5).

These results support the reliability of visual skin tone classification in our study.

Discussion

This prospective study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of pulse oximetry in the pediatric population stratified by objectively classified skin tone using the Fitzpatrick scale. The findings demonstrated a statistically significant overestimation of arterial SpO₂ by pulse oximetry (SpO₂). The magnitude of this bias was significantly higher in dark-skinned children. For these children, there was a mean SpO₂–SaO₂ bias of +1.9%, compared to +0.8% in light-skinned children. The RMSE was also high, indicating reduced measurement precision in dark skin tones. Among children with true hypoxemia (SaO₂<88%), falsely high SpO₂ readings (≥92%) occurred in 35% of dark-skinned children, compared to only 8% in those with light skin. This discrepancy persisted even after adjustment for age and oxygen supplementation, underscoring skin tone as an independent predictor of pulse oximetry bias.

Our findings align with a growing body of evidence indicating skin tone–related discrepancies in pulse oximeter readings. Adult ICU studies have reported similar patterns, with darker-skinned patients exhibiting a mean bias of 1.05% and an accuracy RMSE of 4.15%, compared to 0.34% in lighter-skinned counterparts [6]. In children, a study identified SpO₂–SaO₂ differences of 2.58% in black children versus 0.89% in white children during cardiac procedures [2], consistent with the magnitude of bias found in our study. Moreover, pediatric prospective studies have confirmed the presence of occult hypoxemia, defined as SaO₂<88% despite SpO₂≥92%, in up to 7% of children with darker skin versus 0% in lighter skin groups [7]. A meta-analysis further supported these concerns, reporting a pooled SpO₂ overestimation bias of 1.11% in individuals with darker skin, particularly at SpO₂ below 90% [8]. Our study contributes to pediatric-specific prospective research, addressing a critical knowledge gap by utilizing standardized skin tone classification.

Unlike previous studies that relied on self-reported race or ethnicity as proxies for skin tone, we utilized the Fitzpatrick scale, a validated and reproducible tool for skin type classification. This approach enhances the objectivity and clinical relevance of our findings. Other novel methods such as the Monk skin tone scale and spectrophotometric techniques, have recently been explored for more granular pigmentation assessment [9]. A high inter-rater agreement (κ>0.88) in our study confirmed that visual classification of skin tones remains a practical and reliable method in clinical settings. Discrepancies between race-based and skin tone-based measures have been emphasized in recent frameworks calling for more standardized, multi-dimensional approaches to skin tone assessment [9, 10].

Our findings are consistent with data from the POSTer-Child study, which reported a SpO₂–SaO₂ bias of 3.67% in dark-skinned children compared to 1.37% in light-skinned peers, with occult hypoxemia occurring in 8.3% of the former group [11]. These discrepancies are clinically significant, particularly in settings where SpO₂ thresholds are used for triaging or initiating oxygen therapy. Several studies have also questioned the World Health Organization (WHO)’s current cutoff of SpO₂<90% for initiating oxygen in children with respiratory illness, noting that adverse outcomes have been observed even within the 90–92% range [2].

The overestimation of SpO₂ in darker-skinned children is not a benign artifact but a clinically significant diagnostic gap. Exclusive reliance on pulse oximetry may lead to delayed recognition of hypoxemia, particularly in settings where access to ABG analysis or continuous clinical reassessment is limited. Our findings underscore the need for heightened clinical vigilance when interpreting pulse oximetry in children with darker skin tones; improved calibration algorithms for pulse oximeters that account for melanin levels during design and validation; and incorporation of confirmatory measures (e.g. ABG, capnography, or clinical scoring) in decision-making when readings are borderline or discordant with clinical signs.

This study had several strengths including a prospective design, standardized simultaneous collection of SpO₂ and SaO₂ measurements, and the use of a validated, reproducible skin tone scale with excellent inter-rater reliability. Adjustment for clinical covariates enhances internal validity. However, there were some limitations. The single-center design may limit external generalizability. The Fitzpatrick scale, although standardized, is based on visual assessment and may be influenced by factors such as lighting or the observer's perception. Exclusion of children with hemodynamic instability may reduce applicability to critically ill subgroups. Grouping skin tones into three broad categories, although pragmatic, does not capture the continuous gradations in pigmentation that newer tools aim to address [9, 10].

Conclusion

This study provides strong evidence that pulse oximetry overestimates arterial SpO₂ in children with darker skin tones, leading to a higher risk of undetected hypoxemia. These findings highlight an important disparity in pediatric monitoring, with implications for delayed recognition and treatment of hypoxic conditions in darker-skinned children. The use of an objective, validated skin tone classification method enhances the reliability of findings and emphasizes the need to move beyond race-based proxies in clinical research. Clinicians should be cautious when interpreting SpO₂ values in children with darker skin, particularly when readings appear borderline or inconsistent with clinical signs. This underscores the need for confirmatory testing or supplementary monitoring in critical care settings.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Saveetha Medical College, Chennai, India (Code: 014/12/2024/IEC/SMCH). Informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all children.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and supervision: Navin Umapathy; Investigation and writing: All authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Saveetha University for engaging them in research activity.

References

- Aoki KC, Barrant M, Gai MJ, Handal M, Xu V, Mayrovitz HN. Impacts of skin color and hypoxemia on noninvasive assessment of peripheral blood oxygen saturation: A scoping review. Cureus. 2023; 15(9):e46078. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.46078]

- Hooli S, Colbourn T, Shah MI, Murray K, Mandalakas A, McCollum ED. Pulse oximetry accuracy in children with dark skin tones: Relevance to acute lower respiratory infection care in low- and middle-income countries. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2024; 111(4):736-9. [DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.23-0656] [PMID]

- Sharma M, Brown AW, Powell NM, Rajaram N, Tong L, Mourani PM, et al. Racial and skin color mediated disparities in pulse oximetry in infants and young children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2024; 50:62-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.prrv.2023.12.006] [PMID]

- Sharma M, Pickhardt AJ, McClanahan M, Tong L, Evans MS. Objective assessment and quantification of skin color and melanin in neonates and infants: A state-of-the-art review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025; 42(3):447-56. [DOI:10.1111/pde.15902]

- Martin D, Johns C, Sorrell L, Healy E, Phull M, Olusanya S, et al. Effect of skin tone on the accuracy of the estimation of arterial oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry: A systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2024; 132(5):945-56. [DOI:10.1016/j.bja.2024.01.023] [PMID]

- Fawzy A, Ali H, Dziedzic PH, Potu N, Calvillo E, Golden SH, et al. Skin Pigmentation and pulse oximeter accuracy in the intensive care unit: A pilot prospective study. Am J RespirCrit Care Med. 2024; 210(3):355-8. [DOI:10.1164/rccm.202401-0036LE ]

- Starnes JR, Welch W, Henderson CC, Hudson S, Risney S, Nicholson GT, et al. pulse oximetry and skin tone in children. N Engl J Med. 2025; 392(10):1033-4. [DOI:10.1056/NEJMc2414937] [PMID]

- Singh S, Bennett MR, Chen C, Shin S, Ghanbari H, Nelson BW. Impact of skin pigmentation on pulse oximetry blood oxygenation and wearable pulse rate accuracy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2024; 26:e62769. [DOI:10.2196/62769] [PMID]

- Hao S, Dempsey K, Matos J, Cox CE, Rotemberg V, Gichoya JW, et al. Utility of skin tone on pulse oximetry in critically ill patients: A prospective cohort study. Crit Care Explor. 2024; 6(9):e1133. [Link]

- Hendrickson CM, Lipnick MS, Chen D, Chen D, Law TJ, Pirracchio R, et al. EquiOx: A prospective study of pulse oximeter bias and skin pigmentation in critically ill adults. medRxiv. 2025; 2025.10.06.25337217. [DOI:10.1101/2025.10.06.25337217]

- Starnes JR, Welch W, Henderson CC, Hudson S, Risney S, Nicholson GT, et al. Pulse oximetry and skin tone in children. N Engl J Med. 2025; 392(10):1033-4. [DOI:10.1056/NEJMc2414937] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original Article |

Subject:

Pediatric Gastroenterology

Received: 2025/08/9 | Accepted: 2025/10/18 | Published: 2025/10/18

Received: 2025/08/9 | Accepted: 2025/10/18 | Published: 2025/10/18

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |