Volume 8, Issue 2 (4-2020)

J. Pediatr. Rev 2020, 8(2): 127-132 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ghaemi H R, Zamani H, Babazadeh K, Navaeifar M R. Anomalous Origin of Left Coronary Artery From Pulmonary Artery: A Case Series and Review of Literature. J. Pediatr. Rev 2020; 8 (2) :127-132

URL: http://jpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-246-en.html

URL: http://jpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-246-en.html

1- Rajaie Cardiovascular Medical and Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Modarres Teaching Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Non-communicable Pediatric Diseases Research Center, Health Research Institute, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran.

4- Pediatric Infectious Diseases Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran. , dr.navaifar@gmail.com

2- Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Modarres Teaching Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Non-communicable Pediatric Diseases Research Center, Health Research Institute, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran.

4- Pediatric Infectious Diseases Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran. , dr.navaifar@gmail.com

Keywords: Anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA), Children, Cardiac, Bland-White-Garland syndrome, Coronary vessel anomalies, Cardiovascular diseases

Full-Text [PDF 587 kb]

(2052 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4394 Views)

Full-Text: (1540 Views)

1. Introduction

Congenital coronary artery anomaly is a defect in one or more of the coronary arteries of the heart, which may be related to the origin, structure, and course of these arteries (1). Its incidence varies between 0.2% and 5.6% in the general population (2). Anomalous Left Coronary Artery From The Pulmonary Artery (ALCAPA) is a heart defect presented in 0.25%-0.5% of the children (3) with an incidence of 1 per 300000 live births (4, 5).

The vast majority of affected children, up to 90%, die within the first year of life if ALCAPA is not diagnosed and treated on time (3, 4). This anomaly was first described anatomically by Brooks in 1885 (6). Bland, White, and Garland described the first clinical features with an autopsy finding of ALCAPA in 1933 (7). This anomaly has thus been named the Bland-White-Garland syndrome (8).

2. Case Presentation

In this study, we report 4 pediatric cases of ALCAPA in the north of Iran, Mazandaran Province, from March 2011 to 2016. The informed consent was taken from each cases’ parent.

Case 1

A 2-day-old boy was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit due to respiratory distress and meconium aspiration. Cardiology consultation was performed on the fifth day of admission. Echocardiography showed severe Right Ventricle (RV) and Left Ventricle (LV) dysfunction in addition to pulmonary hypertension. His Tricuspid Regurgitation (TR) gradient was equal to 50 mm Hg, and there was a right to left shunt through a small atrial septal defect. The patient underwent heart failure treatment. During admission, barium swallow was performed due to frequent vomiting episodes, which revealed severe gastro-esophageal reflux.

Congenital coronary artery anomaly is a defect in one or more of the coronary arteries of the heart, which may be related to the origin, structure, and course of these arteries (1). Its incidence varies between 0.2% and 5.6% in the general population (2). Anomalous Left Coronary Artery From The Pulmonary Artery (ALCAPA) is a heart defect presented in 0.25%-0.5% of the children (3) with an incidence of 1 per 300000 live births (4, 5).

The vast majority of affected children, up to 90%, die within the first year of life if ALCAPA is not diagnosed and treated on time (3, 4). This anomaly was first described anatomically by Brooks in 1885 (6). Bland, White, and Garland described the first clinical features with an autopsy finding of ALCAPA in 1933 (7). This anomaly has thus been named the Bland-White-Garland syndrome (8).

2. Case Presentation

In this study, we report 4 pediatric cases of ALCAPA in the north of Iran, Mazandaran Province, from March 2011 to 2016. The informed consent was taken from each cases’ parent.

Case 1

A 2-day-old boy was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit due to respiratory distress and meconium aspiration. Cardiology consultation was performed on the fifth day of admission. Echocardiography showed severe Right Ventricle (RV) and Left Ventricle (LV) dysfunction in addition to pulmonary hypertension. His Tricuspid Regurgitation (TR) gradient was equal to 50 mm Hg, and there was a right to left shunt through a small atrial septal defect. The patient underwent heart failure treatment. During admission, barium swallow was performed due to frequent vomiting episodes, which revealed severe gastro-esophageal reflux.

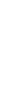

In the second echocardiography, which was performed 5 days later, his RV function improved and TR was 40 mm Hg, but the LV function was still low. In echocardiography, his left coronary artery was connected to the pulmonary artery, but the diastolic flow was not detectable in the pulmonary artery because of its hypertension (Figure 1). The infant was referred to the heart surgery center with a primary diagnosis of ALCAPA. In the follow-up, the diagnosis was confirmed with CT-angiography, then the infant was operated, but unfortunately, he died immediately after surgery.

Case 2

A 3-month-old girl was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit due to fever, respiratory distress, pneumonia, and cardiomegaly on the chest radiogram. Cardiac consultation was requested due to cardiomegaly. The first emergency echocardiography revealed severe cardiac dysfunction and dilatation of the left ventricle, and the Ejection Fraction (EF) was equal to 15%. Due to fever, cardiomegaly, severe cardiac dysfunction, and elevated troponin level, the patient underwent cardiac failure treatment with a primary diagnosis of myocarditis, and also intravenous immunoglobulin was prescribed. She was intubated and in the second echocardiography on the next day, the left coronary to pulmonary artery connection was detected. Because of the patient’s general condition, she could not be transferred to the cardiac surgery center. After the improvement of pneumonia and extubation, in the third echocardiography, a mild diastolic flow was detected in the pulmonary artery. Six days after the admission, she was extubated, and on the next day, following an episode of vomiting, she underwent cardiopulmonary arrest and expired.

Case 3

A 7-month-old male infant was referred to the cardiac clinic due to Failure to Thrive (FTT) and a heart murmur. Echocardiography showed dilated cardiomyopathy, EF=20%, and mitral insufficiency. A careful evaluation revealed the connection of the left coronary artery to the pulmonary artery and distinct retrograde flow in the left coronary artery. The condition was described for the parents, and admission was advised, but they did not refer and follow-up evaluation was impossible maybe due to his referring to another center.

Case 4

A 35-day-old boy was referred to the cardiac clinic due to cardiac murmur. The left ventricle function was decreased in echocardiography, EF=40%, and moderate mitral insufficiency was detected. Evaluation of coronary arteries showed the connection of the left coronary artery to the pulmonary artery, and distinct diastolic flow and reversal flow were not detected in the left coronary artery. The patient was referred to a cardiac surgery center with an initial diagnosis of ALCAPA. In the follow-up, ALCAPA was confirmed, and the patient was operated successfully. The patient is still followed up.

3. Discussion

In fetal life, the pressure of the pulmonary artery is equal to the systemic pressure, allowing for enough myocardial perfusion from the pulmonary artery derived from the anomalous coronary artery (4). However, after birth, the pulmonary artery carries desaturated blood at a pressure that rapidly falls below systemic pressure (9). Hence, the left ventricle is perfused with desaturated hemoglobin at low pressure. This condition predisposes the heart’s muscle to ischemia, especially during activities like feeding or crying (4).

After birth, as the resistance of pulmonary arteries decreases, the flow in the left coronary artery and the collateral, tends to pass into the pulmonary artery rather than into the myocardial blood vessels because the pressure in the pulmonary arteries is lower than the coronary arteries. So, a “coronary artery steal” takes place from the coronary arteries into the pulmonary artery (10). This steal phenomenon further leads to myocardial ischemia, and the ischemia worsens during activities such as feeding and crying (4).

Heart failure may occur because of myocardial infarction in the anterolateral region and or mitral valve dysfunction due to ischemia of anterolateral papillary muscle (11). The heart enlarges, and congestive heart failure often worsens by myocardial infarction in the anterolateral region and mitral valve dysfunction secondary to a dilated mitral ring or infarction of the papillary muscles (11).

The ALCAPA syndrome has two types: the adult type and the infantile type. Patients with good collateral vessels have the adult type of ALCAPA, and those without well-established collateral vessels have the infantile type. The manifestations and outcomes of these two types of ALCAPA are different (12). ALCAPA is often isolated but may be associated with other anomalies, including patent ductus arteriosus, ventricular septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, pulmonary atresia, hemitruncus, and Coarctation of the Aorta (CoA) (3, 4, 11).

The affected infants experience pneumonia and heart failure in the early weeks and months after birth (13). Dyspnea, feeding intolerance, diaphoresis, and FTT are common symptoms that may resemble those of infantile colic, gastroesophageal reflux, and bronchitis (4).

Infants have episodic attacks of restlessness which are equivalent to angina pectoris (11). In infancy and early childhood, ALCAPA is characterized by heart failure symptoms (14). While in late childhood and adolescence, mitral insufficiency (due to papillary muscle infarction), and sudden cardiac death are common manifestations of the disease (14). Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM) is an important differential diagnosis for ALCAPA, and this vascular anomaly should be considered in all children with DCM or isolated mitral insufficiency (11).

Distinct cardiomegaly and evidence of pulmonary edema are seen in the chest radiogram (4, 13). Abnormal Q wave and inverted T in the leads I and AVL and V4-V6 are found in EKG, which can help the diagnosis (13). Also, 2D echocardiography and color Doppler are diagnostic and angiography is not necessary (4). Color Doppler evaluation shows the retrograde flow from an aberrant left coronary artery into the pulmonary artery (4). Other findings that help the diagnosis are hyper-density of the mitral papillary muscles, increased septal collateral flow in color Doppler, and significant right coronary artery dilatation (13). Other diagnostic modalities include CT angiography and MRI (4).

ALCAPA is a rare disease that needs a cardiac operation, but in the case of inappropriate treatment, its mortality reaches up to 90% within the first year of life (3). Of four reported cases in this study, 2 cases expired. One of them died before the surgery and another one immediately after the operation, one case is alive now, and we miss follow up of the latter one.

Review protocol

A quick review was made on online databases for articles in the English language that reported ALCAPA cases in pediatric age. We searched the keywords of “children”, “pediatric”, “ALCAPA”, “Anomalous left coronary”, and “Bland0-White-Garland syndrome” in the Google Scholar and PubMed without time limitation. Finally, we found 18 published case reports with 201 cases (Table 1).

Zheng et al. reported 19 cases during 16 years (12 boys and 7 girls). The age range of them was 2.5 months to 13 years, an average of 12 months. Operation mortality was 5 (26%) patients (13).

In Uysal et al. study for 20 years, 7 ALCAPA cases were reported, and 5 of them were girls. In 5 patients, the clinical manifestation was heart failure and all of them aged less than 6 months, and two of them were referred due to heart murmur (15).

In the case series of Brotherton et al. (11) 5 patients were reported for 5 years, 3 girls and 2 boys, and all of them were under 5 years old. In our case series for 5 years, 4 ALCAPA cases, 3 boys and 1 girl, were reported and all of them aged less than 1 year old and 2 of them were neonates.

Some cases of adulthood ALCAPA were reported by Fierens et al. (16) (a 73-year-old woman) and Selzman et al. (a 23-year-old woman) (14).

Symptoms of the disease in infancy are various and can resemble common complications of infancy, including colic, gastroesophageal reflux, lactose intolerance, and pneumonia. The ALCAPA diagnosis can be mistaken by dilated cardiomyopathy and endocardial fibroelastosis (13). In Ojala et al. study for 27 years, 29 cases were reported, of which 4 patients were admitted with the initial diagnosis of pulmonary infection (3).

In our reported patients, an infant was diagnosed due to pneumonia and cardiac insufficiency. In another neonate, the ALCAPA was diagnosed due to cardiac insufficiency and another one due to a heart murmur and FTT. One infant was diagnosed due to the detection of a heart murmur.

For diagnosis of ALCAPA, 2D, and color echography are diagnostic, and in color Doppler, retrograde flow in the pulmonary artery is observed (4). In this case series, in the first case, the aberrant coronary artery was detected in 2D echocardiography, but due to some degrees of pulmonary hypertension, reversed flow was not detected in the pulmonary artery.

Case 2

A 3-month-old girl was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit due to fever, respiratory distress, pneumonia, and cardiomegaly on the chest radiogram. Cardiac consultation was requested due to cardiomegaly. The first emergency echocardiography revealed severe cardiac dysfunction and dilatation of the left ventricle, and the Ejection Fraction (EF) was equal to 15%. Due to fever, cardiomegaly, severe cardiac dysfunction, and elevated troponin level, the patient underwent cardiac failure treatment with a primary diagnosis of myocarditis, and also intravenous immunoglobulin was prescribed. She was intubated and in the second echocardiography on the next day, the left coronary to pulmonary artery connection was detected. Because of the patient’s general condition, she could not be transferred to the cardiac surgery center. After the improvement of pneumonia and extubation, in the third echocardiography, a mild diastolic flow was detected in the pulmonary artery. Six days after the admission, she was extubated, and on the next day, following an episode of vomiting, she underwent cardiopulmonary arrest and expired.

Case 3

A 7-month-old male infant was referred to the cardiac clinic due to Failure to Thrive (FTT) and a heart murmur. Echocardiography showed dilated cardiomyopathy, EF=20%, and mitral insufficiency. A careful evaluation revealed the connection of the left coronary artery to the pulmonary artery and distinct retrograde flow in the left coronary artery. The condition was described for the parents, and admission was advised, but they did not refer and follow-up evaluation was impossible maybe due to his referring to another center.

Case 4

A 35-day-old boy was referred to the cardiac clinic due to cardiac murmur. The left ventricle function was decreased in echocardiography, EF=40%, and moderate mitral insufficiency was detected. Evaluation of coronary arteries showed the connection of the left coronary artery to the pulmonary artery, and distinct diastolic flow and reversal flow were not detected in the left coronary artery. The patient was referred to a cardiac surgery center with an initial diagnosis of ALCAPA. In the follow-up, ALCAPA was confirmed, and the patient was operated successfully. The patient is still followed up.

3. Discussion

In fetal life, the pressure of the pulmonary artery is equal to the systemic pressure, allowing for enough myocardial perfusion from the pulmonary artery derived from the anomalous coronary artery (4). However, after birth, the pulmonary artery carries desaturated blood at a pressure that rapidly falls below systemic pressure (9). Hence, the left ventricle is perfused with desaturated hemoglobin at low pressure. This condition predisposes the heart’s muscle to ischemia, especially during activities like feeding or crying (4).

After birth, as the resistance of pulmonary arteries decreases, the flow in the left coronary artery and the collateral, tends to pass into the pulmonary artery rather than into the myocardial blood vessels because the pressure in the pulmonary arteries is lower than the coronary arteries. So, a “coronary artery steal” takes place from the coronary arteries into the pulmonary artery (10). This steal phenomenon further leads to myocardial ischemia, and the ischemia worsens during activities such as feeding and crying (4).

Heart failure may occur because of myocardial infarction in the anterolateral region and or mitral valve dysfunction due to ischemia of anterolateral papillary muscle (11). The heart enlarges, and congestive heart failure often worsens by myocardial infarction in the anterolateral region and mitral valve dysfunction secondary to a dilated mitral ring or infarction of the papillary muscles (11).

The ALCAPA syndrome has two types: the adult type and the infantile type. Patients with good collateral vessels have the adult type of ALCAPA, and those without well-established collateral vessels have the infantile type. The manifestations and outcomes of these two types of ALCAPA are different (12). ALCAPA is often isolated but may be associated with other anomalies, including patent ductus arteriosus, ventricular septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, pulmonary atresia, hemitruncus, and Coarctation of the Aorta (CoA) (3, 4, 11).

The affected infants experience pneumonia and heart failure in the early weeks and months after birth (13). Dyspnea, feeding intolerance, diaphoresis, and FTT are common symptoms that may resemble those of infantile colic, gastroesophageal reflux, and bronchitis (4).

Infants have episodic attacks of restlessness which are equivalent to angina pectoris (11). In infancy and early childhood, ALCAPA is characterized by heart failure symptoms (14). While in late childhood and adolescence, mitral insufficiency (due to papillary muscle infarction), and sudden cardiac death are common manifestations of the disease (14). Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM) is an important differential diagnosis for ALCAPA, and this vascular anomaly should be considered in all children with DCM or isolated mitral insufficiency (11).

Distinct cardiomegaly and evidence of pulmonary edema are seen in the chest radiogram (4, 13). Abnormal Q wave and inverted T in the leads I and AVL and V4-V6 are found in EKG, which can help the diagnosis (13). Also, 2D echocardiography and color Doppler are diagnostic and angiography is not necessary (4). Color Doppler evaluation shows the retrograde flow from an aberrant left coronary artery into the pulmonary artery (4). Other findings that help the diagnosis are hyper-density of the mitral papillary muscles, increased septal collateral flow in color Doppler, and significant right coronary artery dilatation (13). Other diagnostic modalities include CT angiography and MRI (4).

ALCAPA is a rare disease that needs a cardiac operation, but in the case of inappropriate treatment, its mortality reaches up to 90% within the first year of life (3). Of four reported cases in this study, 2 cases expired. One of them died before the surgery and another one immediately after the operation, one case is alive now, and we miss follow up of the latter one.

Review protocol

A quick review was made on online databases for articles in the English language that reported ALCAPA cases in pediatric age. We searched the keywords of “children”, “pediatric”, “ALCAPA”, “Anomalous left coronary”, and “Bland0-White-Garland syndrome” in the Google Scholar and PubMed without time limitation. Finally, we found 18 published case reports with 201 cases (Table 1).

Zheng et al. reported 19 cases during 16 years (12 boys and 7 girls). The age range of them was 2.5 months to 13 years, an average of 12 months. Operation mortality was 5 (26%) patients (13).

In Uysal et al. study for 20 years, 7 ALCAPA cases were reported, and 5 of them were girls. In 5 patients, the clinical manifestation was heart failure and all of them aged less than 6 months, and two of them were referred due to heart murmur (15).

In the case series of Brotherton et al. (11) 5 patients were reported for 5 years, 3 girls and 2 boys, and all of them were under 5 years old. In our case series for 5 years, 4 ALCAPA cases, 3 boys and 1 girl, were reported and all of them aged less than 1 year old and 2 of them were neonates.

Some cases of adulthood ALCAPA were reported by Fierens et al. (16) (a 73-year-old woman) and Selzman et al. (a 23-year-old woman) (14).

Symptoms of the disease in infancy are various and can resemble common complications of infancy, including colic, gastroesophageal reflux, lactose intolerance, and pneumonia. The ALCAPA diagnosis can be mistaken by dilated cardiomyopathy and endocardial fibroelastosis (13). In Ojala et al. study for 27 years, 29 cases were reported, of which 4 patients were admitted with the initial diagnosis of pulmonary infection (3).

In our reported patients, an infant was diagnosed due to pneumonia and cardiac insufficiency. In another neonate, the ALCAPA was diagnosed due to cardiac insufficiency and another one due to a heart murmur and FTT. One infant was diagnosed due to the detection of a heart murmur.

For diagnosis of ALCAPA, 2D, and color echography are diagnostic, and in color Doppler, retrograde flow in the pulmonary artery is observed (4). In this case series, in the first case, the aberrant coronary artery was detected in 2D echocardiography, but due to some degrees of pulmonary hypertension, reversed flow was not detected in the pulmonary artery.

In the second case, the aberrant coronary artery was detected too, and the reversed flow was not observed in the pulmonary artery. Some days later, following recovery from pneumonia and extubation, a mild reversed flow was detected in the pulmonary artery.

A clear inverted flow was reported in the third case, who was a 7-month-old infant who is justified according to the age of the infant and decreased pulmonary hypertension.

In the first and second cases, ALCAPA was diagnosed in the second echocardiography, presumably due to heart failure and precision in the connection of coronary arteries. All of our cases had some evidence of heart failure and lacked any other congenital heart disease.

4. Conclusions

Although rare, in infants and children presented with dilated cardiomyopathy, decreased heart function, or myocardial infarction, ALCAPA should be considered as an important differential diagnosis, and the connection of coronary arteries to aorta should be carefully checked in echocardiography.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The parents of the patient provided informed written consent for the release of results and data.

Funding

The study did not receive any financial support.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and design: Hamid Reza Ghaemi and Mohammad Reza Navaeifar; Review of data: Kazem Babazadeh; Drafting of the manuscript: Hassan Zamani; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Hamid Reza Ghaemi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Angelini P. Coronary artery anomalies: An entity in search of an identity. Circulation. 2007; 115(10):1296-305. [DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.618082] [PMID]

Silva A, Baptista MJ, Araujo E. Congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries. Portuguese Journal of Cardiology. 2018; 37(4):341-50. [DOI:10.1016/j.repc.2017.09.015] [PMID]

Ojala T, Salminen J, Happonen JM, Pihkala J, Jokinen E, Sairanen H. Excellent functional result in children after correction of anomalous origin of left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery-a population-based complete follow-up study. Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery. 2010; 10(1):70-5. [DOI:10.1510/icvts.2009.209627] [PMID]

Lardhi AA. Anomalous origin of left coronary artery from pulmonary artery: A rare cause of myocardial infarction in children. Journal of Family & Community Medicine. 2010; 17(3):113-6. [DOI:10.4103/1319-1683.74319] [PMID] [PMCID]

Secinaro A, Ntsinjana H, Tann O, Schuler PK, Muthurangu V, Hughes M, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance findings in repaired Anomalous Left Coronary Artery to Pulmonary Artery connection (ALCAPA). Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2011; 13(1):27. [DOI:10.1186/1532-429X-13-27] [PMID] [PMCID]

Brooks HSJ. Two cases of an abnormal coronary artery of the heart, arising from the pulmonary artery, with some remarks upon the effect of this anomaly in producing cirsoid dilatation of the vessels. Transactions of the Academy of Medicine in Ireland. 1885; 3(1):447. [DOI:10.1007/BF03173347]

Cowles RA, Berdon WE. Bland-White-Garland syndrome of Anomalous Left Coronary Artery arising from the Pulmonary Artery (ALCAPA): A historical review. Pediatric Radiology. 2007; 37(9):890-5. [DOI:10.1007/s00247-007-0544-8] [PMID]

Bland EF, White PD, Garland J. Congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries: Report of an unusual case associated with cardiac hypertrophy. American Heart Journal. 1933; 8(6):787-801. [DOI:10.1016/S0002-8703(33)90140-4]

Allen HD, Driscoll DJ, Shaddy RE, Feltes TF. Moss & Adams’ heart disease in infants, children, and adolescents: Including the fetus and young adult. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

Esfehani RJ, Hosseini S, Ebrahimi M, Jalalyazdi M, Gharaee AM. Anomalous Left Coronary Artery from the Pulmonary Artery presenting with atypical chest pain in an adult: A case report. The Journal of Tehran University Heart Center. 2017; 12(3):128-30. [PMCID] [PMID]

Brotherton H, Philip RK. Anomalous Left Coronary Artery from Pulmonary Artery (ALCAPA) in infants: A 5-year review in a defined birth cohort. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2008; 167(1):43-6. [DOI:10.1007/s00431-007-0423-1] [PMID]

Moeinipour A, Abbassi Teshnisi M, Mottaghi Moghadam H, Zirak N, Hassanzadeh R, Hoseinikhah H, et al. The Anomalous origin of the Left Coronary Artery from the Pulmonary Artery (ALCAPA): A Case Series and Brief Review. International Journal of Pediatrics. 2016;4(2):1397-405. [DOI:10.22038/IJP.2016.6438]

Zheng J, Ding W, Xiao Y, Jin M, Zhang G, Cheng P, et al. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery in children: 15 years experience. Pediatric Cardiology. 2011; 32(1):24-31. [DOI:10.1007/s00246-010-9798-2] [PMID]

Selzman CH, Zimmerman MA, Campbell DN. ALCAPA in an adult with preserved left ventricular function. Journal of Cardiac Surgery. 2003; 18(1):25-8. [DOI:10.1046/j.1540-8191.2003.01908.x] [PMID]

Uysal F, Bostan OM, Semizel E, Signak IS, Asut E, Cil E. Congenital anomalies of coronary arteries in children: The evaluation of 22 patients. Pediatric Cardiology. 2014; 35(5):778-84. [DOI:10.1007/s00246-013-0852-8] [PMID]

Fierens C, Budts W, Denef B, Van de Werf F. A 72 year old woman with ALCAPA. Heart. 2000; 83(1):e2. [DOI:10.1136/heart.83.1.e2] [PMID] [PMCID]

Ma F, Zhou K, Shi X, Wang X, Zhang Y, Li Y, et al. Misdiagnosed Anomalous Left Coronary Artery from the Pulmonary Artery as endocardial fibroelastosis in infancy: A case series. Medicine. 2017; 96(24):e7199. [DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000007199] [PMID] [PMCID]

Zhang HL, Li SJ, Wang X, Yan J, Hua ZD. Preoperative evaluation and midterm outcomes after the surgical correction of Anomalous origin of the Left Coronary Artery from the Pulmonary Artery in 50 infants and children. Chinese Medical Journal. 2017; 130(23):2816-22. [DOI:10.4103/0366-6999.219156] [PMID] [PMCID]

Walker TC, Renno MS, Parra DA, Guthrie SO. Case Report: Neonatal ventricular fibrillation and an elusive ALCAPA: Things are not always as they seem. British Medical Journal, Case Reports. 2016; pii: bcr2015214239. [DOI:10.1136/bcr-2015-214239] [PMID] [PMCID]

Rodriguez-Gonzalez M, Tirado AM, Hosseinpour R, de Soto JS. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery: Diagnoses and surgical results in 12 pediatric patients. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 2015; 42(4):350-6. [DOI:10.14503/THIJ-13-3849] [PMID] [PMCID]

Muzaffar T, Ganie FA, Swamy SG. The surgical outcome of anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery. International Cardiovascular Research Journal. 2014; 8(2):57-60. [PMCID] [PMID]

Molaei A, Hemmati BR, Khosroshahi H, Malaki M, Zakeri R. Misdiagnosis of bland-white-garland syndrome: Report of two cases with different presentations. Journal of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Research. 2014; 6(1):65-7. [DOI:10.5681/jcvtr.2014.013] [PMCID] [PMID]

Aliku TO, Lubega S, Lwabi P. A case of anomalous origin of the left coronary artery presenting with acute myocardial infarction and cardiovascular collapse. African Health Sciences. 2014; 14(1):223-7. [DOI:10.4314/ahs.v14i1.35] [PMID] [PMCID]

Szmigielska A, Roszkowska-Blaim M, Gołąbek-Dylewska M, Tomik A, Brzewski M, Werner B. Bland-White-Garland syndrome: A rare and serious cause of failure to thrive. The American Journal of Case Reports. 2013; 14:370-2. [DOI:10.12659/AJCR.889112] [PMID] [PMCID]

Smith III DE, Adams R, Argilla M, Phoon CK, Chun AJ, Bendel M, et al. A unique ALCAPA variant in a neonate. Journal of Cardiac Surgery: Including Mechanical and Biological Support for the Heart and Lungs. 2013; 28(3):306-8. [DOI:10.1111/jocs.12079] [PMID]

Salzer-Muhar U, Proll E, Kronik G. Intercoronary collateral flow detected by Doppler colour flow mapping is an additional diagnostic sign in children with anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery. Heart. 1993; 70(6):558-9. [DOI:10.1136/hrt.70.6.558] [PMID] [PMCID]

A clear inverted flow was reported in the third case, who was a 7-month-old infant who is justified according to the age of the infant and decreased pulmonary hypertension.

In the first and second cases, ALCAPA was diagnosed in the second echocardiography, presumably due to heart failure and precision in the connection of coronary arteries. All of our cases had some evidence of heart failure and lacked any other congenital heart disease.

4. Conclusions

Although rare, in infants and children presented with dilated cardiomyopathy, decreased heart function, or myocardial infarction, ALCAPA should be considered as an important differential diagnosis, and the connection of coronary arteries to aorta should be carefully checked in echocardiography.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The parents of the patient provided informed written consent for the release of results and data.

Funding

The study did not receive any financial support.

Authors contributions

Conceptualization and design: Hamid Reza Ghaemi and Mohammad Reza Navaeifar; Review of data: Kazem Babazadeh; Drafting of the manuscript: Hassan Zamani; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Hamid Reza Ghaemi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Angelini P. Coronary artery anomalies: An entity in search of an identity. Circulation. 2007; 115(10):1296-305. [DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.618082] [PMID]

Silva A, Baptista MJ, Araujo E. Congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries. Portuguese Journal of Cardiology. 2018; 37(4):341-50. [DOI:10.1016/j.repc.2017.09.015] [PMID]

Ojala T, Salminen J, Happonen JM, Pihkala J, Jokinen E, Sairanen H. Excellent functional result in children after correction of anomalous origin of left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery-a population-based complete follow-up study. Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery. 2010; 10(1):70-5. [DOI:10.1510/icvts.2009.209627] [PMID]

Lardhi AA. Anomalous origin of left coronary artery from pulmonary artery: A rare cause of myocardial infarction in children. Journal of Family & Community Medicine. 2010; 17(3):113-6. [DOI:10.4103/1319-1683.74319] [PMID] [PMCID]

Secinaro A, Ntsinjana H, Tann O, Schuler PK, Muthurangu V, Hughes M, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance findings in repaired Anomalous Left Coronary Artery to Pulmonary Artery connection (ALCAPA). Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2011; 13(1):27. [DOI:10.1186/1532-429X-13-27] [PMID] [PMCID]

Brooks HSJ. Two cases of an abnormal coronary artery of the heart, arising from the pulmonary artery, with some remarks upon the effect of this anomaly in producing cirsoid dilatation of the vessels. Transactions of the Academy of Medicine in Ireland. 1885; 3(1):447. [DOI:10.1007/BF03173347]

Cowles RA, Berdon WE. Bland-White-Garland syndrome of Anomalous Left Coronary Artery arising from the Pulmonary Artery (ALCAPA): A historical review. Pediatric Radiology. 2007; 37(9):890-5. [DOI:10.1007/s00247-007-0544-8] [PMID]

Bland EF, White PD, Garland J. Congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries: Report of an unusual case associated with cardiac hypertrophy. American Heart Journal. 1933; 8(6):787-801. [DOI:10.1016/S0002-8703(33)90140-4]

Allen HD, Driscoll DJ, Shaddy RE, Feltes TF. Moss & Adams’ heart disease in infants, children, and adolescents: Including the fetus and young adult. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

Esfehani RJ, Hosseini S, Ebrahimi M, Jalalyazdi M, Gharaee AM. Anomalous Left Coronary Artery from the Pulmonary Artery presenting with atypical chest pain in an adult: A case report. The Journal of Tehran University Heart Center. 2017; 12(3):128-30. [PMCID] [PMID]

Brotherton H, Philip RK. Anomalous Left Coronary Artery from Pulmonary Artery (ALCAPA) in infants: A 5-year review in a defined birth cohort. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2008; 167(1):43-6. [DOI:10.1007/s00431-007-0423-1] [PMID]

Moeinipour A, Abbassi Teshnisi M, Mottaghi Moghadam H, Zirak N, Hassanzadeh R, Hoseinikhah H, et al. The Anomalous origin of the Left Coronary Artery from the Pulmonary Artery (ALCAPA): A Case Series and Brief Review. International Journal of Pediatrics. 2016;4(2):1397-405. [DOI:10.22038/IJP.2016.6438]

Zheng J, Ding W, Xiao Y, Jin M, Zhang G, Cheng P, et al. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery in children: 15 years experience. Pediatric Cardiology. 2011; 32(1):24-31. [DOI:10.1007/s00246-010-9798-2] [PMID]

Selzman CH, Zimmerman MA, Campbell DN. ALCAPA in an adult with preserved left ventricular function. Journal of Cardiac Surgery. 2003; 18(1):25-8. [DOI:10.1046/j.1540-8191.2003.01908.x] [PMID]

Uysal F, Bostan OM, Semizel E, Signak IS, Asut E, Cil E. Congenital anomalies of coronary arteries in children: The evaluation of 22 patients. Pediatric Cardiology. 2014; 35(5):778-84. [DOI:10.1007/s00246-013-0852-8] [PMID]

Fierens C, Budts W, Denef B, Van de Werf F. A 72 year old woman with ALCAPA. Heart. 2000; 83(1):e2. [DOI:10.1136/heart.83.1.e2] [PMID] [PMCID]

Ma F, Zhou K, Shi X, Wang X, Zhang Y, Li Y, et al. Misdiagnosed Anomalous Left Coronary Artery from the Pulmonary Artery as endocardial fibroelastosis in infancy: A case series. Medicine. 2017; 96(24):e7199. [DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000007199] [PMID] [PMCID]

Zhang HL, Li SJ, Wang X, Yan J, Hua ZD. Preoperative evaluation and midterm outcomes after the surgical correction of Anomalous origin of the Left Coronary Artery from the Pulmonary Artery in 50 infants and children. Chinese Medical Journal. 2017; 130(23):2816-22. [DOI:10.4103/0366-6999.219156] [PMID] [PMCID]

Walker TC, Renno MS, Parra DA, Guthrie SO. Case Report: Neonatal ventricular fibrillation and an elusive ALCAPA: Things are not always as they seem. British Medical Journal, Case Reports. 2016; pii: bcr2015214239. [DOI:10.1136/bcr-2015-214239] [PMID] [PMCID]

Rodriguez-Gonzalez M, Tirado AM, Hosseinpour R, de Soto JS. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery: Diagnoses and surgical results in 12 pediatric patients. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 2015; 42(4):350-6. [DOI:10.14503/THIJ-13-3849] [PMID] [PMCID]

Muzaffar T, Ganie FA, Swamy SG. The surgical outcome of anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery. International Cardiovascular Research Journal. 2014; 8(2):57-60. [PMCID] [PMID]

Molaei A, Hemmati BR, Khosroshahi H, Malaki M, Zakeri R. Misdiagnosis of bland-white-garland syndrome: Report of two cases with different presentations. Journal of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Research. 2014; 6(1):65-7. [DOI:10.5681/jcvtr.2014.013] [PMCID] [PMID]

Aliku TO, Lubega S, Lwabi P. A case of anomalous origin of the left coronary artery presenting with acute myocardial infarction and cardiovascular collapse. African Health Sciences. 2014; 14(1):223-7. [DOI:10.4314/ahs.v14i1.35] [PMID] [PMCID]

Szmigielska A, Roszkowska-Blaim M, Gołąbek-Dylewska M, Tomik A, Brzewski M, Werner B. Bland-White-Garland syndrome: A rare and serious cause of failure to thrive. The American Journal of Case Reports. 2013; 14:370-2. [DOI:10.12659/AJCR.889112] [PMID] [PMCID]

Smith III DE, Adams R, Argilla M, Phoon CK, Chun AJ, Bendel M, et al. A unique ALCAPA variant in a neonate. Journal of Cardiac Surgery: Including Mechanical and Biological Support for the Heart and Lungs. 2013; 28(3):306-8. [DOI:10.1111/jocs.12079] [PMID]

Salzer-Muhar U, Proll E, Kronik G. Intercoronary collateral flow detected by Doppler colour flow mapping is an additional diagnostic sign in children with anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery. Heart. 1993; 70(6):558-9. [DOI:10.1136/hrt.70.6.558] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Case Report and Review of Literature |

Subject:

Pediatric Cardiology

Received: 2019/06/16 | Accepted: 2019/09/7 | Published: 2020/04/1

Received: 2019/06/16 | Accepted: 2019/09/7 | Published: 2020/04/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |