Volume 7, Issue 4 (10-2019)

J. Pediatr. Rev 2019, 7(4): 223-228 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Salari F, Bani Adam L, Arshi S, Bemanian M H, Fallahpour M, Nabavi M. Netherton Syndrome: A Case Report With Literature Review. J. Pediatr. Rev 2019; 7 (4) :223-228

URL: http://jpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-212-en.html

URL: http://jpr.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-212-en.html

Fereshteh Salari1

, Leila Bani Adam1

, Leila Bani Adam1

, Saba Arshi1

, Saba Arshi1

, Mohammad Hassan Bemanian1

, Mohammad Hassan Bemanian1

, Morteza Fallahpour1

, Morteza Fallahpour1

, Mohammad Nabavi

, Mohammad Nabavi

2

2

, Leila Bani Adam1

, Leila Bani Adam1

, Saba Arshi1

, Saba Arshi1

, Mohammad Hassan Bemanian1

, Mohammad Hassan Bemanian1

, Morteza Fallahpour1

, Morteza Fallahpour1

, Mohammad Nabavi

, Mohammad Nabavi

2

2

1- Department of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Hazrat Rasoul Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Hazrat Rasoul Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. , mnabavi44@yahoo.com

2- Department of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Hazrat Rasoul Hospital, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. , mnabavi44@yahoo.com

Full-Text [PDF 852 kb]

(2892 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4719 Views)

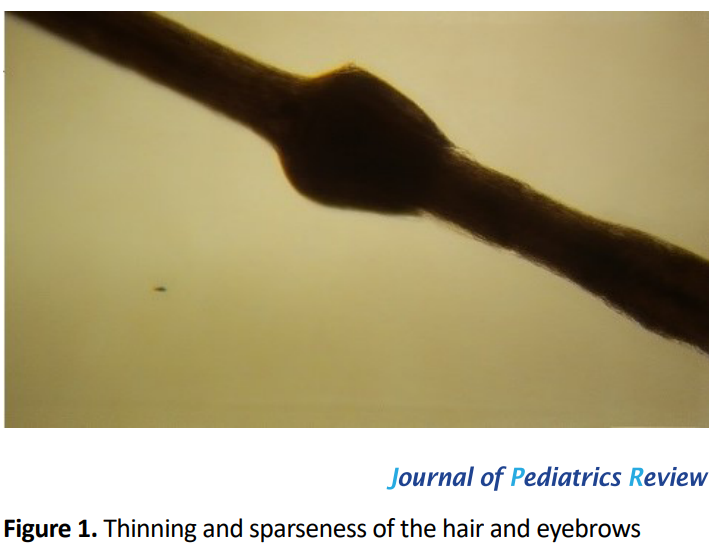

In the extremities, especially in the antecubital (Figure 2a) and popliteal area (Figure 2b), there were diffuse polycyclic erythematous patches surrounded by a double-edged scales characteristic of ILC. Erythema and desquamation were also dominant in other parts of the body, including the back and posterior auricular area.

He was born after a normal pregnancy course without any perinatal complications. Immediately post-partum generalized erythema appeared with associated ichthyosis. After a few months, erythematous rash changed and transformed into desquamated patches and plaques during infancy. He had recurrent skin infections and worsening of his cutaneous lesions with some contact allergens as well as food allergens. Signs and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux and allergic rhinosinusitis without any evidence of asthma appeared soon in his life. The patient was mentally normal with normal physical growth. He was in the 50th percentile for weight and height. There was a history of parental consanguinity, and his mother had atopic dermatitis.

His laboratory data revealed only an elevated IgE level (1280 IU/mL) and the other immunologic tests did not show significant results. There was a leukocyte count of 7800/μL with 10% eosinophil. Skin prick test showed sensitivity to some foods, including nuts, milk, wheat, and tomato.

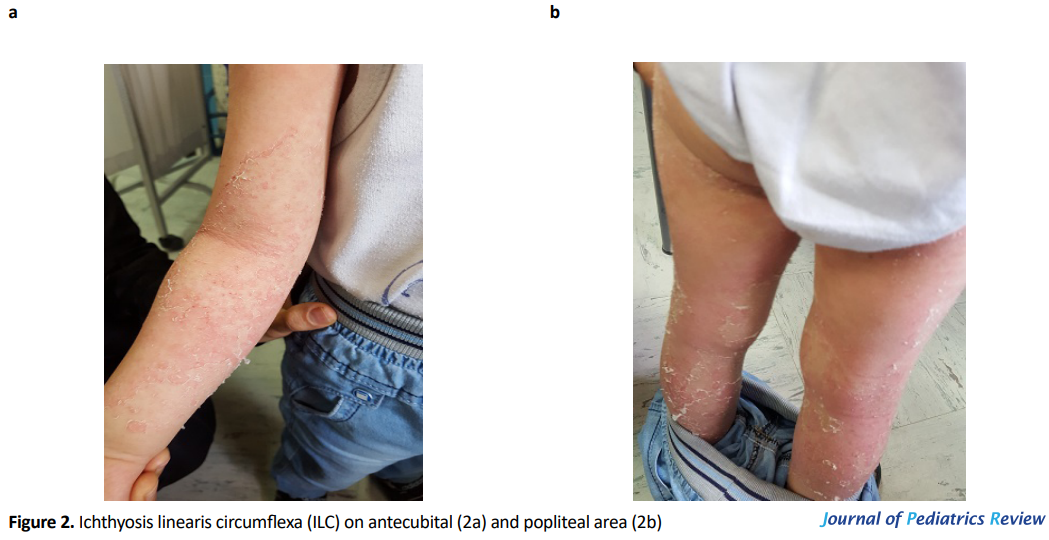

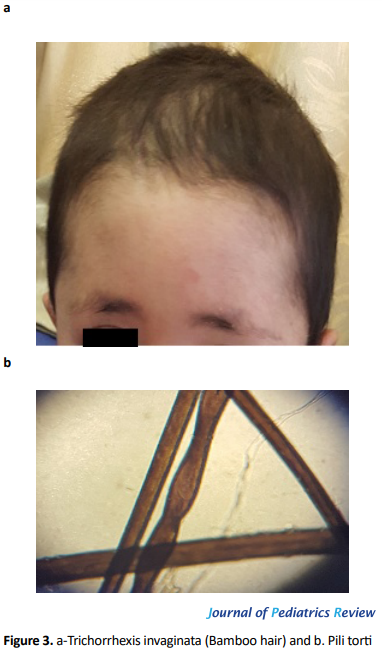

Light microscopy of his hair shaft indicated classic trichorrhexis invaginata (Bamboo hair) (Figure 3a) and pili torti (Figure 3b).

Diagnosis of NS was made based on clinical as well as histological findings, including ILC and trichorrhexis invaginata. Cutaneous lesions are under relatively controlled state using topical medications such as moisturizers, topical corticosteroid ointments, and keratolytic agents.

3. Discussion and Literature Review

Netherton Syndrome (NS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by the triad of congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma with a typical form referred to as Ichthyosis Linearis Circumflexa (ILC), hair shaft defect diagnosed with either trichorrhexis invaginata or bamboo hair, and atopic diathesis (4, 5).

In 1937, Touraine and Solente first noted the association between hair-shaft defects (bamboo node) and ichthyosiform erythroderma. Còmel first introduced the term ichthyosis linearis circumflexa in 1949. Finally, in 1958, Netherton reported a young girl with generalized scaly dermatitis and fragile nodular hair-shaft deformities, named as trichorrhexis nodosa (7). The frequency of trichorrhexis invaginata is unknown. Nearly 200 cases have been reported worldwide (7). NS (Mendelian Inheritance in Man [MIM] #256500) is an autosomal recessive disease as a result of mutations of both copies of the SPINK5 gene (localized to band 5q31-32) (8). Each SPINK5 mutation results in the production of LEKTI protein with different length, resulting in genotype/phenotype associations in cutaneous severity and vulnerability to atopic dermatitis (9).

Clinically, the triad of trichorrhexis invaginata “bamboo hair” or “ball and socket” hair shaft deformity, congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma/ichthyosis linearis circumflexa, and an atopic diathesis recognizes NS. Atopic manifestations include atopic dermatitis, asthma, allergic rhinitis, urticaria, angioedema, food anaphylaxis, blood hypereosinophilia, and elevated serum IgE. Recurrent infections, especially bacterial infections of the skin, are common and occur in at least 30% of the affected patients such as this case (10).

In 2013, Boskabadi et al. reported a 63-day-old boy with a diagnosis of NS with severe failure to thrive, diarrhea, and generalized erythroderma and scaling. That case shows that children with ichthyosiform dermatosis, diarrhea, and growth failure may have an underlying disease such as NS (11). In the current case, although the child had erythroderma and desquamation immediately after birth, we missed the diagnosis of NS because of no family history of the syndrome. Also, his hair was not affected in the early infancy period. Of course, the infant’s hair may be sparse in the early infancy. Besides, ILC commonly does not occur before the age of two, and it may be misdiagnosed as allergic diseases such as atopic dermatitis or other skin disorders. Finally, the nature and severity of the skin lesions are variable between patients and or within a patient, rendering the diagnosis difficult.

Typically, the diagnosis is delayed until the appearance of trichorrhexis invaginata, which is pathognomonic. Therefore, the hair examination should be carried out early so that the diagnosis would not be missed. Otherwise, the delayed diagnosis in atypical cases can be confirmed, if necessary, by identification of a germline SPINK5 mutation by DNA sequencing. However, in our case, because of the high cost of performing this test, his parents refused for genetic testing. Anyway, this test was not necessary for diagnosis as the patient had a typical clinical triad. A similar case of NS was reported by Saleem et al. in 2018 about a two-year-old boy with intractable skin manifestations, multiple food allergies, who was initially treated as atopic dermatitis (12).

Currently, there is no known definitive cure or satisfactory treatment for NS. Treatment modalities such as topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, topical retinoids, narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy, psoralen, ultraviolet irradiation, and oral acitretin have been used with varying success. Intravenous immunoglobulin and anti-TNF-α are therapeutic options for severe cases (13, 14). Like other similar case reports, our reported case demonstrated the importance of attention to other differential diagnoses in severe and refractory eruptions, especially with early onset disorders at neonatal age. Table 1 presents a summary of data derived from the literature review.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The parents of participant were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; They also assured about the confidentiality of the information.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed in designing, running, and writing all parts of the research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Full-Text: (1406 Views)

1. Introduction

Netherton Syndrome (NS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, an atopic diathesis, and hair-shaft abnormality known as trichorrhexis invaginata (1). The incidence of NS is estimated to be approximately 1 in 200000 (2). It is also the cause of up to 18% of congenital erythrodermas (3). This syndrome is associated with a type of mutation in the SPINK5 gene, which encodes a serine protease inhibitor called LEKTI (lymphoepithelial Kazal-type-related Inhibitor) (1). Triad of trichorrhexis invaginata, Ichthyosis Linearis Circumflexa (ILC), and an atopic diathesis usually are seen in NS (4). Trichorrhexis invaginata is a necessary criterion in the diagnosis of NS (5, 6).

Atopic diathesis can include eczema-like eruptions, atopic dermatitis, asthma, pruritus, allergic rhinitis, angioedema, urticaria, elevated serum IgE, and or hypereosinophilia (4). Many treatments have been attempted, including topical corticosteroids, low-dose oral corticosteroids, tretinoin, topical emollients, and psoralen ultraviolet A therapy (1). The objective of this case report is to illustrate the NS in a patient with severe eczema atopic dermatitis-like eruption. In addition, a short review was done related to this case.

2. Case Presentation

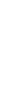

A 41-month-old boy was referred to the clinic of Allergy and Immunology with generalized erythema since the first day of his life. Dermatological examination revealed thinning and sparseness of his hair and eyebrows with excessive scalp scaling, erythema, and patchy scaling in the perioral area and face and generalized ichthyosiform xerosis (Figure 1).

Netherton Syndrome (NS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, an atopic diathesis, and hair-shaft abnormality known as trichorrhexis invaginata (1). The incidence of NS is estimated to be approximately 1 in 200000 (2). It is also the cause of up to 18% of congenital erythrodermas (3). This syndrome is associated with a type of mutation in the SPINK5 gene, which encodes a serine protease inhibitor called LEKTI (lymphoepithelial Kazal-type-related Inhibitor) (1). Triad of trichorrhexis invaginata, Ichthyosis Linearis Circumflexa (ILC), and an atopic diathesis usually are seen in NS (4). Trichorrhexis invaginata is a necessary criterion in the diagnosis of NS (5, 6).

Atopic diathesis can include eczema-like eruptions, atopic dermatitis, asthma, pruritus, allergic rhinitis, angioedema, urticaria, elevated serum IgE, and or hypereosinophilia (4). Many treatments have been attempted, including topical corticosteroids, low-dose oral corticosteroids, tretinoin, topical emollients, and psoralen ultraviolet A therapy (1). The objective of this case report is to illustrate the NS in a patient with severe eczema atopic dermatitis-like eruption. In addition, a short review was done related to this case.

2. Case Presentation

A 41-month-old boy was referred to the clinic of Allergy and Immunology with generalized erythema since the first day of his life. Dermatological examination revealed thinning and sparseness of his hair and eyebrows with excessive scalp scaling, erythema, and patchy scaling in the perioral area and face and generalized ichthyosiform xerosis (Figure 1).

In the extremities, especially in the antecubital (Figure 2a) and popliteal area (Figure 2b), there were diffuse polycyclic erythematous patches surrounded by a double-edged scales characteristic of ILC. Erythema and desquamation were also dominant in other parts of the body, including the back and posterior auricular area.

He was born after a normal pregnancy course without any perinatal complications. Immediately post-partum generalized erythema appeared with associated ichthyosis. After a few months, erythematous rash changed and transformed into desquamated patches and plaques during infancy. He had recurrent skin infections and worsening of his cutaneous lesions with some contact allergens as well as food allergens. Signs and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux and allergic rhinosinusitis without any evidence of asthma appeared soon in his life. The patient was mentally normal with normal physical growth. He was in the 50th percentile for weight and height. There was a history of parental consanguinity, and his mother had atopic dermatitis.

His laboratory data revealed only an elevated IgE level (1280 IU/mL) and the other immunologic tests did not show significant results. There was a leukocyte count of 7800/μL with 10% eosinophil. Skin prick test showed sensitivity to some foods, including nuts, milk, wheat, and tomato.

Light microscopy of his hair shaft indicated classic trichorrhexis invaginata (Bamboo hair) (Figure 3a) and pili torti (Figure 3b).

Diagnosis of NS was made based on clinical as well as histological findings, including ILC and trichorrhexis invaginata. Cutaneous lesions are under relatively controlled state using topical medications such as moisturizers, topical corticosteroid ointments, and keratolytic agents.

3. Discussion and Literature Review

Netherton Syndrome (NS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by the triad of congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma with a typical form referred to as Ichthyosis Linearis Circumflexa (ILC), hair shaft defect diagnosed with either trichorrhexis invaginata or bamboo hair, and atopic diathesis (4, 5).

In 1937, Touraine and Solente first noted the association between hair-shaft defects (bamboo node) and ichthyosiform erythroderma. Còmel first introduced the term ichthyosis linearis circumflexa in 1949. Finally, in 1958, Netherton reported a young girl with generalized scaly dermatitis and fragile nodular hair-shaft deformities, named as trichorrhexis nodosa (7). The frequency of trichorrhexis invaginata is unknown. Nearly 200 cases have been reported worldwide (7). NS (Mendelian Inheritance in Man [MIM] #256500) is an autosomal recessive disease as a result of mutations of both copies of the SPINK5 gene (localized to band 5q31-32) (8). Each SPINK5 mutation results in the production of LEKTI protein with different length, resulting in genotype/phenotype associations in cutaneous severity and vulnerability to atopic dermatitis (9).

Clinically, the triad of trichorrhexis invaginata “bamboo hair” or “ball and socket” hair shaft deformity, congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma/ichthyosis linearis circumflexa, and an atopic diathesis recognizes NS. Atopic manifestations include atopic dermatitis, asthma, allergic rhinitis, urticaria, angioedema, food anaphylaxis, blood hypereosinophilia, and elevated serum IgE. Recurrent infections, especially bacterial infections of the skin, are common and occur in at least 30% of the affected patients such as this case (10).

In 2013, Boskabadi et al. reported a 63-day-old boy with a diagnosis of NS with severe failure to thrive, diarrhea, and generalized erythroderma and scaling. That case shows that children with ichthyosiform dermatosis, diarrhea, and growth failure may have an underlying disease such as NS (11). In the current case, although the child had erythroderma and desquamation immediately after birth, we missed the diagnosis of NS because of no family history of the syndrome. Also, his hair was not affected in the early infancy period. Of course, the infant’s hair may be sparse in the early infancy. Besides, ILC commonly does not occur before the age of two, and it may be misdiagnosed as allergic diseases such as atopic dermatitis or other skin disorders. Finally, the nature and severity of the skin lesions are variable between patients and or within a patient, rendering the diagnosis difficult.

Typically, the diagnosis is delayed until the appearance of trichorrhexis invaginata, which is pathognomonic. Therefore, the hair examination should be carried out early so that the diagnosis would not be missed. Otherwise, the delayed diagnosis in atypical cases can be confirmed, if necessary, by identification of a germline SPINK5 mutation by DNA sequencing. However, in our case, because of the high cost of performing this test, his parents refused for genetic testing. Anyway, this test was not necessary for diagnosis as the patient had a typical clinical triad. A similar case of NS was reported by Saleem et al. in 2018 about a two-year-old boy with intractable skin manifestations, multiple food allergies, who was initially treated as atopic dermatitis (12).

Currently, there is no known definitive cure or satisfactory treatment for NS. Treatment modalities such as topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, topical retinoids, narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy, psoralen, ultraviolet irradiation, and oral acitretin have been used with varying success. Intravenous immunoglobulin and anti-TNF-α are therapeutic options for severe cases (13, 14). Like other similar case reports, our reported case demonstrated the importance of attention to other differential diagnoses in severe and refractory eruptions, especially with early onset disorders at neonatal age. Table 1 presents a summary of data derived from the literature review.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All ethical principles were considered in this article. The parents of participant were informed about the purpose of the research and its implementation stages; They also assured about the confidentiality of the information.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed in designing, running, and writing all parts of the research.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Sun JD, Linden KG. Netherton syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. International Journal of Dermatology. 2006; 45(6):693-7. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02637.x] [PMID]

- Emre S, Metin A, Demirseren DD, Yorulmaz A, Onursever A, Kaftan B. Two siblings with Netherton syndrome. Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences. 2010; 40(5):819-23. [DOI:10.3906/sag-0904-12]

- Bitoun E, Chavanas S, Irvine AD, Lonie L, Bodemer C, Paradisi M, et al. Netherton syndrome: Disease expression and spectrum of SPINK5 mutations in 21 families. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2002; 118(2):352-61. [DOI:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01603.x] [PMID]

- Greene SL, Muller SA. Netherton’s syndrome: Report of a case and review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1985; 13(2):329-37. [DOI:10.1016/S0190-9622(85)70170-3]

- Altman J, Stroud J. Neterton’s syndrome and ichthyosis linearis circumflexa. Archives Dermatology. 1969; 100(5):550-8. [DOI:10.1001/archderm.100.5.550] [PMID]

- Dawber R. Clinical aspects of hair disorders. Dermatologic Clinics. 1996; 14:753-72. [DOI:10.1016/S0733-8635(05)70402-2]

- McGevna LF. Trichorrhexis invaginata (Netherton Syndrome or bamboo hair) [Internet]. 2017 [Updated 2017 December 18]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1071656-overview

- Wang S, Olt S, Schoefmann N, Stuetz A, Winiski A, Wolff‐Winiski B. SPINK5 knockdown in organotypic human skin culture as a model system for Netherton syndrome: Effect of genetic inhibition of serine proteases kallikrein 5 and kallikrein 7. Experimental Dermatology. 2014; 23(7):524-6. [DOI:10.1111/exd.12451] [PMID]

- Namkung JH, Lee JE, Kim E, Byun JY, Kim S, Shin ES, et al. Hint for association of single nucleotide polymorphisms and haplotype in SPINK5 gene with atopic dermatitis in Koreans. Experimental Dermatology. 2010; 19(12):1048-53. [DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01142.x] [PMID]

- Leung AK, Barankin B, Leong K. An 8-year-old child with delayed diagnosis of Netherton syndrome. Case Reports in Pediatrics. 2018; 2018(9434916):1-4. [DOI:10.1155/2018/9434916] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Boskabadi H, Maamouri G, Mafinejad S. Netherton syndrome, a case report and review of literature. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics. 2013; 23(5):611-2. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Saleem HMK, Shahid MF, Shahbaz A, Sohail A, Shahid MA, Sachmechi I. Netherton syndrome: A case report and review of literature. Cureus. 2018; 10(7):e3070. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.3070]

- Small AM, Cordoro KM. Netherton syndrome mimicking pustular psoriasis: Clinical implications and response to intravenous immunoglobulin. Pediatric Dermatology. 2016; 33(3):e222-e3. [DOI:10.1111/pde.12856] [PMID]

- Roda Â, Mendonça-Sanches M, Travassos AR, Soares-de-Almeida L, Metze D. Infliximab therapy for Netherton syndrome: A case report. JAAD Case Reports. 2017; 3(6):550-2. [DOI:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.07.019] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Case & Review |

Subject:

Allergy and Clinical Immunology

Received: 2018/11/13 | Accepted: 2019/02/13 | Published: 2019/10/1

Received: 2018/11/13 | Accepted: 2019/02/13 | Published: 2019/10/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |